Small fish want to be them. Predators fear them. At first glance, you'd be forgiven for dismissing the tiny fang blenny as an easy meal ticket. However while these plankton feeders and aquarium favorites might not look like they could hurt a fly, their venom can easily make a predator's blood pressure drop like one.

In a series of feeding experiments conducted in the 1970s, the zoologist George Losey observed that after taking a forktail blenny (M. atrodorsalis) into its mouth, the grouper's typical reaction was a "violent quivering of the head with distension of the jaws and operculi." The fish eventually swam out unscathed. The grouper, on the other hand, was so scarred by the experience that it developed an aversion to this particular genus of fish.

Fast forward more than 40 years later, and researchers from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the University of Queensland (UQ) have discovered a possible reason to explain how this tiny fish gets the better of its attackers: their venom, which comprises not one but a combination of three types of toxins, seen for the first time in a fish: a neuropeptide that can cause a drop in blood pressure. This has also been found in cone snail venom; in a lipase similar to one made by scorpions and bees that can cause inflammation; and in an opioid peptide called encephalin, which suppresses pain.

"To put that into human terms, opioid peptides would be the last thing an elite Olympic swimmer would use as performance-enhancing substances," says co-author and University of Queensland researcher Bryan Fry. "They would be more likely to drown than win gold."

Yet, despite its effect on fish, what makes the fang blenny venom so intriguing is that it doesn't seem to induce the kind of excruciating pain one would expect of such a toxic cocktail – at least not in mammals. Indeed, lab mice that were injected with its venom did not show any overt reaction though their blood pressure did drop by nearly 40 percent. On his part, Losey, who received two bites on the hips during his study, likened them to "a mild bee sting" (note: your mileage might vary) with the puncture wounds becoming inflamed after bleeding freely "for about 10 minutes."

The researchers surmise that the drop in blood pressure is probably due to the neuropeptide and opioid components, which can leave predators feeling disoriented and prevent them from pursuing the fish. "By slowing down potential predators, the fang blennies have a chance to escape," says Fry. "While the feeling of pain is not produced, opioids can produce sensations of extremely unpleasant nausea and dizziness in mammals."

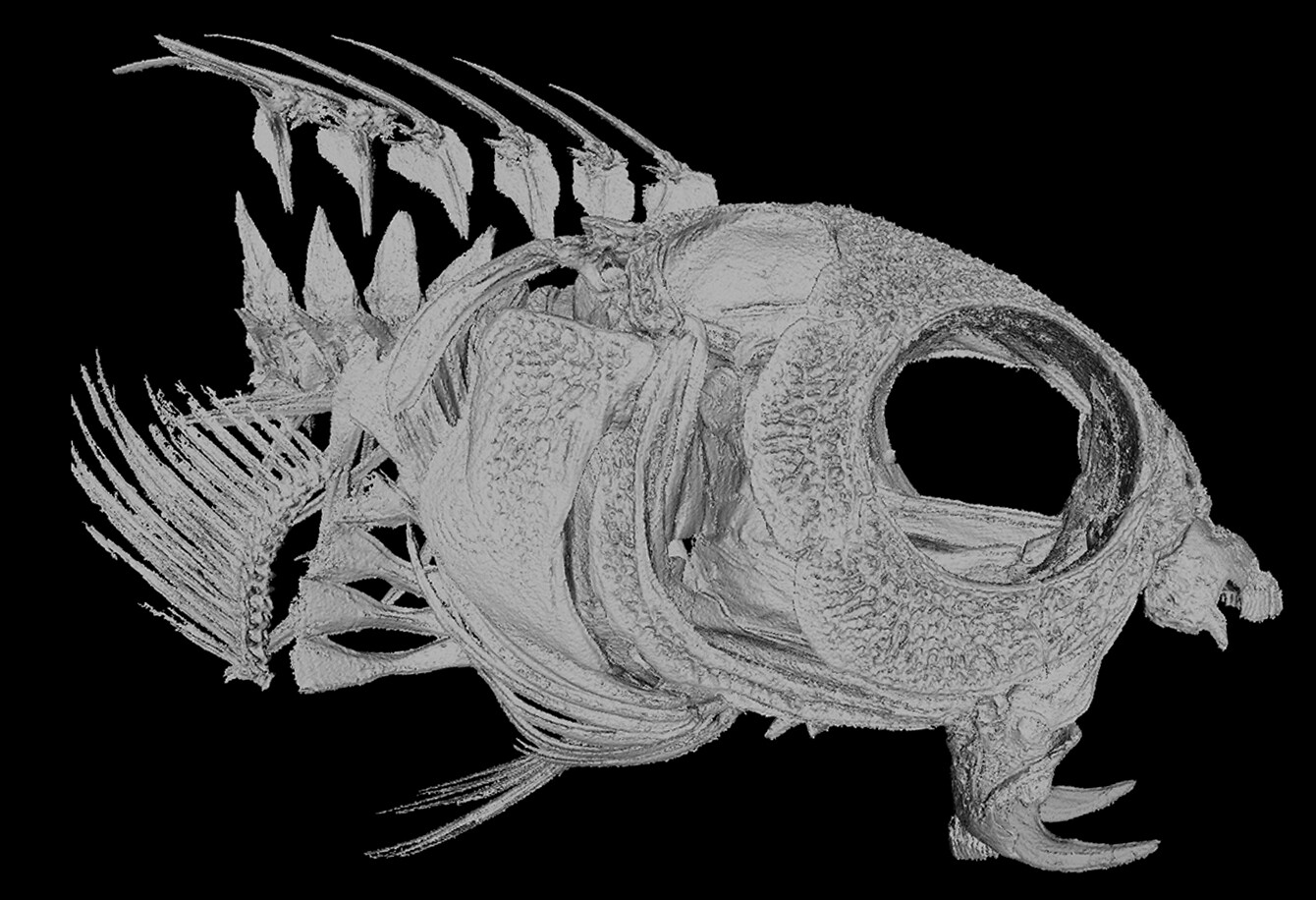

Of the 100 fang blenny species in existence, only 30, which belong to the genus Meiacanthus, have venomous glands, which suggests that their fangs developed before their venom glands, which is unusual, says study co-author Nicholas Casewell from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. "In snakes for example, we've found that some sort of venom secretions evolved first, before the evolution of the elaborate venom delivery mechanism," he explains.

Since fish can't talk, scientists can only speculate how exactly the fang blenny venom affects them, but one thing is for certain: after being bitten, predators expunge them from their diet for life. For other small fish and non-venomous fang bennies, this is reason enough for them to mimic its colors and patterns – and exploit other fishes' fear of the venomous fang blenny.

"Predatory fish will not eat those fishes because they think they are venomous and going to cause them harm, but this protection provided also allows some of these mimics to get very close to unsuspecting fish to feed on them, by picking on their scales as a micropredator," says Casewell. "All of this mimicry, all of these interactions at the community level, ultimately are stimulated by the venom system that some of these fish have."

Compared to snakes, spiders and scorpions, venomous fish – of which there are some 2,500 species – are a neglected group when it comes to the study of toxins, which is a shame, say researchers, as they could open the door to therapies for a wide range of ailments. For Fry, this is one more reason to protect nature.

"These fish are fascinating in their behaviour. They fearlessly take on potential predators while also intensively fighting for space with similar sized fish," he says. "If we lose the Great Barrier Reef, we will lose animals like the fang blenny and its unique venom that could be the source of the next blockbuster pain-killing drug."

The study was published in Current Biology.

Sources: University of Queensland, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine