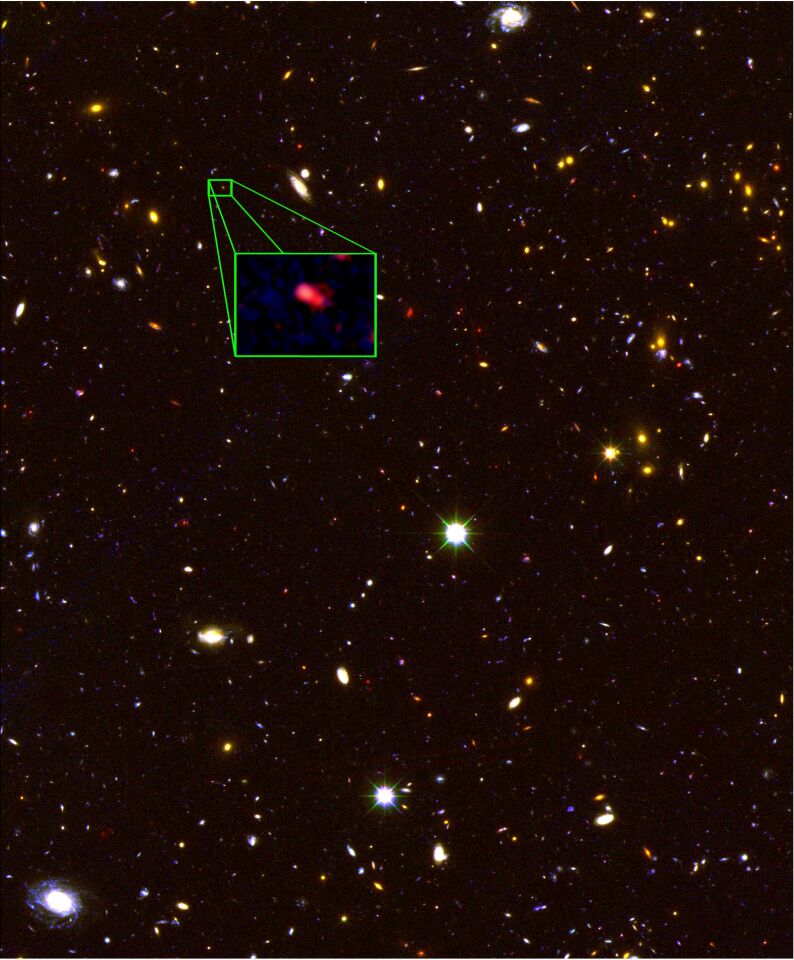

Astronomers at UC Riverside have combined observations from space and ground telescopes to discover what they say is the oldest known galaxy with a precisely measured distance, seen as it was just 700 million years after the Big Bang.

The astronomers started their search from the database of about 100,000 galaxies collected for the Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Galactic Legacy Survey (CANDELS), a project that was granted close to 900 hours of observation time on the Hubble Space Telescope.

After selecting 43 galaxy candidates, the scientists put to use the new MOSFIRE instrument for the Keck ground telescope in Hawaii, which was designed to be extremely sensitive to infrared light (allowing precise measurements of the redshift) and to target multiple celestial objects at the same time.

Astronomers Steven Finkelstein and colleagues narrowed down their search to 43 galaxy candidates and, thanks to the new instrument, were able to obtain higher-quality observations than ever before.

The team found that the galaxy z8-GND-5296, which we see as it was just 700 million years after the beginning of the Universe, appears to be forming new stars at a very high pace, producing about 330 times the mass of the Sun every year. This is in line with other very early galaxies that astronomers have found (by contrast, our much older Milky Way only produces two to three stars a year).

Astronomers have claimed to have discovered even earlier galaxies, but this finding was unique because it was the first time that the distance could be confirmed through high-precision spectroscopy.

While redshift is perhaps a very common way of judging the distance of celestial objects, astronomers can perform more accurate measurements by analyzing their hydrogen signature. In the most distant known galaxies, the hydrogen appears to be in a neutral state, which makes them much harder to detect. However, the ionized hydrogen signature in GND-5296 allowed the scientists to confirm their finding for the first time for a galaxy of this epoch.

Out of all the 43 candidates, GND-5296 was the only one with ionized hydrogen in its surroundings, while the others, all in its neighborhood, seem to contain hydrogen only at its neutral state. This suggests that the researchers have stumbled upon an area of great interest in which the transition from neutral to ionized hydrogen is just beginning to occur.

The astronomers didn't expect to be able to detect such a distant galaxy in their survey of a relatively small size, which suggests that the early Universe could have seen much larger numbers of young and highly active galaxies than previously thought.

The next generation of very large ground-based telescopes (which includes the Thirty Meter Telescope and the Giant Magellan Telescope, both to be completed by the end of the decade) is expected to help astronomers study these very distant celestial bodies in much greater detail.

The astronomers describe the finding in a recent issue of the journal Nature.

Source: UC Riverside