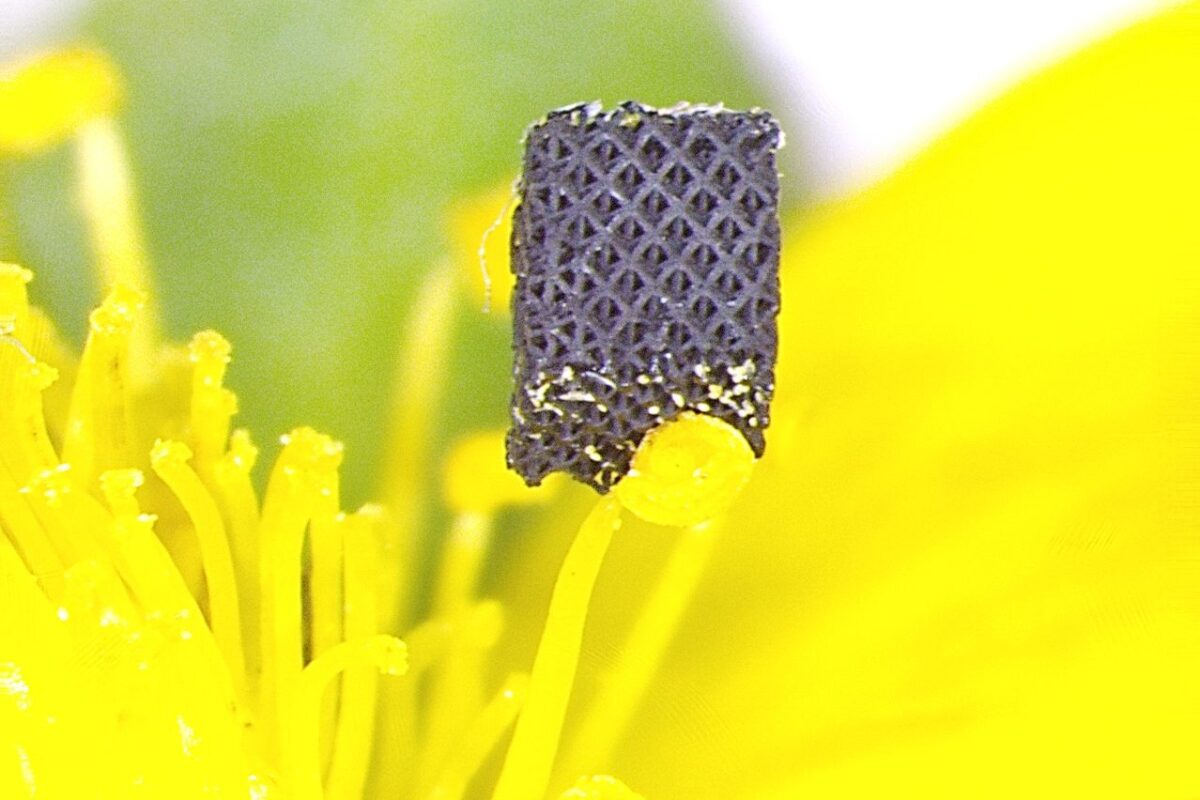

Graphene is famous as a two-dimensional material, but to really make the most of the stuff we need to coax it back into 3D forms. Now researchers from Virginia Tech have developed a new way to 3D print graphene aerogels with a far higher resolution than previously possible.

Normally graphene takes the form of a flat sheet of carbon just a single atom thick, and although that's useful in some circumstances it needs to be made three-dimensional for practical use. Just stacking sheets doesn't cut it – that lessens its strength and the unique electrical, chemical and optical properties. After all, you're basically turning it back into plain old graphite that way.

A porous form known as graphene aerogel manages to keep most of the qualities of 2D graphene in a 3D form. The trick is to keep graphene layers separate from each other, which the aerogel does using air trapped in its pores. Other methods have involved using lasers to forge graphene into 3D shapes, compressing it into porous coral-like structures, and 3D printing it as a foam, supported by carbon nanotubes.

The problem with graphene aerogels is that it's not the easiest thing to mold into required shapes. In the past it's been extruded in filaments as thin as 100 micrometers, but finer detail than that has been out of reach. The new study set out to improve that resolution.

"With that technique, there's very limited structures you can create because there's no support and the resolution is quite limited, so you can't get freeform factors," says Xiaoyu Zheng, an author of the study. "What we did was to get these graphene layers to be architected into any shape that you want with high resolution."

For the new method, the researchers make a hydrogel out of graphene oxide, complete with crosslinked sheets. This is then broken apart using ultrasound and combined with acrylate polymers, which are sensitive to light. The team can then use projection micro-stereolithography – a very precise form of 3D printing that can build structures on the microscale – to create long rigid chains of the polymer, with graphene oxide trapped inside. Finally the mixture is placed in a furnace, which burns away the polymers and leaves the graphene aerogel behind.

This technique, the team says, can be used to create three-dimensional graphene in just about any shape you could want. The resolution is also much finer – down to 10 micrometers – making it an order of magnitude better than was previously possible.

"We've been able to show you can make a complex, three-dimensional architecture of graphene while still preserving some of its intrinsic prime properties," says Zheng. "Usually when you try to 3D print graphene or scale up, you lose most of their lucrative mechanical properties found in its single sheet form."

The research was published in the journal Material Horizons.

Source: Virginia Tech