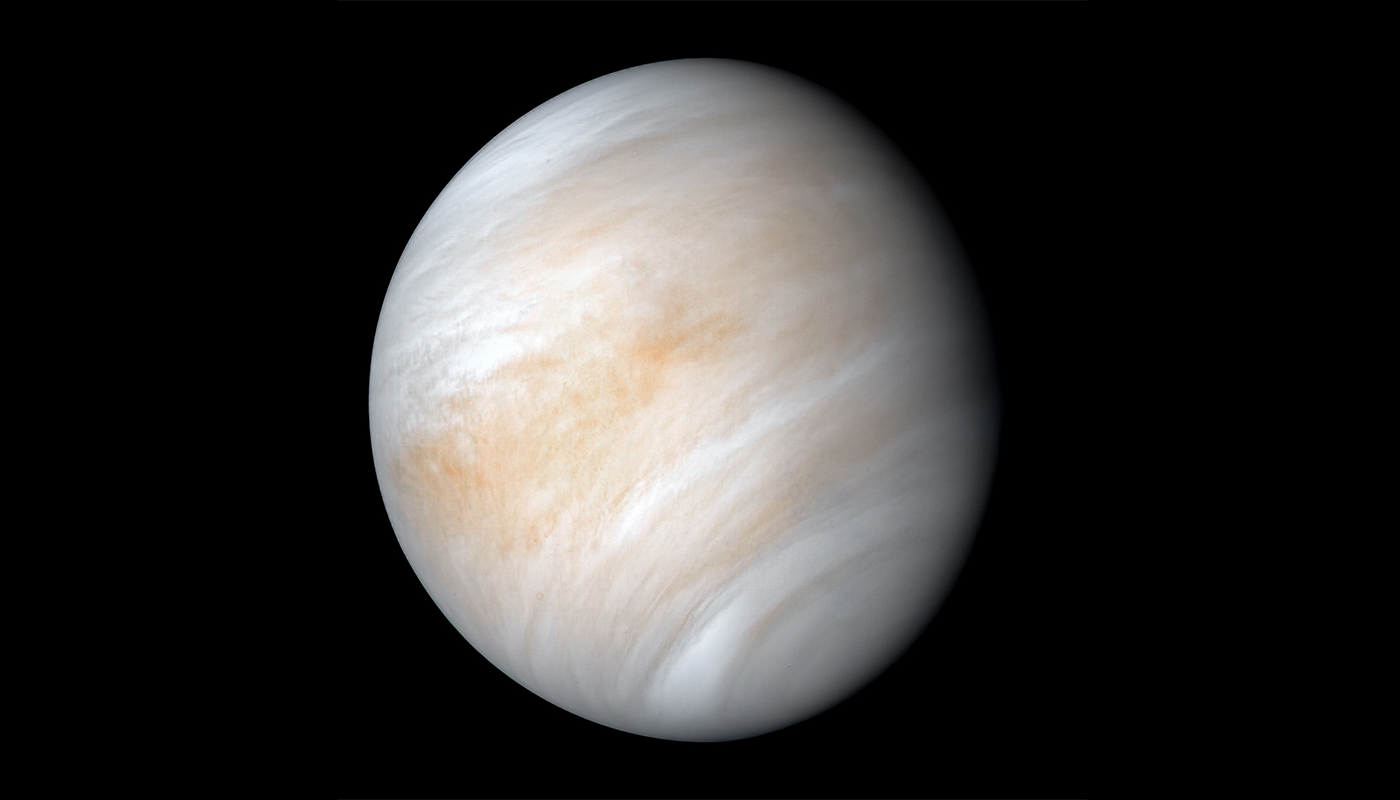

This week, astronomers published research with profound implications for our search for life beyond Earth, revealing that the gas phosphine had been found in the atmosphere of Venus. This discovery could hardly have come at a better time for Rocket Lab, which in a short space of time has demonstrated an impressive capability to launch things into orbit, but is now setting its sights further afield, including plans for a private mission to Venus in 2023. New Atlas spoke with the company’s CEO Peter Beck about the road ahead, his long-time fascination with the planet and the machinery that he plans to use to explore it.

Since first reaching orbit in early 2018, Rocket Lab has made some serious waves in the space game. Its Electron rocket has gone on to deliver satellites to orbit for NASA, DARPA and the US Air Force, and the company also recently began to test out recovery methods to enable recycling of the booster’s first stage.

Rocket Lab also swiftly put a July launchpad failure behind it to return to action in August, and then earlier this month launched its own in-house-built satellite for the first time. This Photon spacecraft is designed to provide things like navigation and communications support for smaller satellites, and also serve as a full-feature spacecraft capable of carrying out its own interplanetary missions. Recently, Rocket Lab also won a contract to provide the launch services for NASA’s Capstone mission to the Moon, in which its Photon platform will be used to deliver a CubeSat into lunar orbit.

While all this was going on, the Rocket Lab team has been quietly preparing for an exploratory mission to Venus. So, as the space community ponders the life-bearing potential of our next-door neighbor in light of this week’s discovery, Rocket Lab finds itself particularly well-placed to probe its mysteries.

What follows is a transcript of our conversation on the topic with Beck.

New Atlas: Obviously the discovery of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus was a big deal. What did you make of the news?

Beck: It’s long been hypothesized that within atmosphere, especially around that 50-km (30-mi)(altitude) zone, there could quite possibly be some form of life given it is relatively temperate. To actually have found some markers of life in that region is a huge step forward.

You’ve said previously that you’re “madly in love with Venus.” Can you talk a bit about your fascination with the planet? When did it begin and why?

I’ve always had a huge fascination with Venus. I spent a lot of time as a kid looking at it through a telescope and Venus was always fascinating to me because it’s really, in a lot of respects, one of the most Earth-like planets in our solar system, it’s the same size and it has a very large atmosphere.

A relatively short time ago, on a galactic scale at least, Venus looked a lot more like Earth than it does now. Venus is kind of Earth’s sister gone wrong. It’s Earth sister, but where climate change has just completely run away. So in that respect, there’s a lot to learn from Venus to make sure we don’t go down the same path, and a lot of really incredible discoveries to be made.

There are kind of three accepted places in our solar system where environments may be such that they could, at least potentially, harbor some sort of life. And as I mentioned, the Venus clouds have been long thought to be one of those. That’s always been really fascinating to me as well.

When we won our NASA contract to go to the Moon a year ago, instead of just building a spacecraft that was capable of getting to the Moon, I said to the team, 'let’s build one that can also get to Venus while we’re at it.' Because if we can get to the Moon, it’s not that much harder to get to Venus. So we’ve been working on our own private mission to Venus for a while now, and it’s just great that there is a lot more interest in the planet, and there have been some new discoveries that give us much more impetus to get there.

So it’s clearly exciting on a personal level for you, but how about your motivation to get to Venus as the CEO of Rocket Lab, can you speak to that from a business perspective?

From a personal level, we were doing Venus well before Venus was cool. The intention here was always a private mission. From a business standpoint, what we’ve tried to create here is a platform that can really affordably and really quickly go and explore other planets and other celestial bodies in our solar system. And instead of going to a planet once a decade and it costs us a few billion dollars, we need to iterate the science much more quickly than that.

The platform we’ve created here to deliver NASA to the Moon, and then our own mission, and then other missions after that, is a platform that’s really low cost, really quick and really capable, to move forward the state of the art in planetary and celestial sciences.

You’re speaking of the Photon spacecraft?

Yes, correct. So our first Photon satellite launched a few weeks ago on Electron, and the Photon Lunar, which is basically the same spacecraft as the Venus spacecraft, is launching early next year to go to the Moon for NASA. And then 2023 is the optimal window to arrive at Venus in a short time frame.

I’m interested to know what technical challenges still stand in the way. So between now and 2023 I’m assuming there are still some problems to overcome for your engineers. Can you speak about that and how achievable you think that timeline is?

I mean, we’ve got to build a spacecraft to travel halfway across the solar system to deliver a probe into the atmosphere at 11 kilometers a second to search for life, it’s no biggie right?

When you put it that way … (laughs)

No, there are some serious technical challenges here. The spacecraft element I’m not too worried about. Don’t get me wrong, it’s incredibly difficult, but we will have had a mission to the Moon by then, and we have a satellite in orbit already, so for that part of it, we should have a lot of experience by then.

Entering a probe into the atmosphere is non-trivial. We’re coming in at extreme velocities. But probably the hardest bit is the instrument. So defining an instrument to search for life is non-trivial, because you have to make some assumptions about what that life is in the first place. And to do it in a very small package, and get the data back to Earth in the time that the probe is scorching through the Venusian atmosphere, that is the bit that is very complex and challenging.

But the beauty is that it doesn’t cost billions of dollars and we can have many cracks at it, so I’m happy to fund one mission to Venus, but we certainly hope we can convince other folks to do a whole campaign of missions, where we can iterate the science and take a little bit more risk.

How do you see this mission to Venus fitting in alongside other larger missions under consideration, from the likes of NASA, Russia and ESA?

It’s all great science. We’re going there because we feel it’s important and we didn’t feel that there was enough emphasis on the planet. So it’s great that others are also now redirecting efforts to that destination. At the end of the day this is a win for Venus and a win for science. So I think this is wonderful.

In many parts, our desire here to do a private mission was to spawn interest for other scientific discoveries. At the end of the day, if there are more people going and we’re learning more, then that’s what we want. So the catalyst, whether that be us or now some potential signs of life, I think is just wonderful.

Back to the Photon spacecraft, the launch must have been very exciting for you guys. Can you tell us about the significance of this, and the role the spacecraft will play in a mission to Venus?

This particular spacecraft was really the first operational Photon satellite in orbit. We used it to validate a number of our technologies and we are using it as a bit of a development testing platform while it’s in orbit. We can let our customers play with it as well, and use it to see how we’ve created and architected the systems.

We build rockets but we also build satellites for people. Photon can fly on Electron or not fly on Electron. The whole space systems division is about creating those end-to-end solutions. So we are obviously using it for our own internal benefit, but also for external customers to understand the platform.

Now, this probe that you will use to explore the atmosphere of Venus … it’s interesting what you said about how in going to look for signs of life, you’re making some assumptions about the type of life you might find. So how far out are you from finalizing the instruments that you will put on that probe, and what sort of things do you consider in that decision-making?

We’re working with the science team that actually made the phosphine discovery, we have been for a while. Look, I’m not a planetary scientist specializing in astrobiology so this is their time to really help define that. And it is our job to take those instrument requirements and get them there. That’s the way I look at it.

You had that launchpad failure recently, and managed to bounce back into action pretty quickly. Was that process as smooth as you would have liked? It seemed that way from the outside looking in ...

We’ve enjoyed an incredible record of reliability, and there is not a launch vehicle ever that has not failed in its flight history. We never ever want that, and we do everything we can to ensure that that never happens, our approach here is extreme diligence.

It wasn’t like the launch vehicle just blew up, it was a very graceful failure that we were able to define the root cause of very quickly. And through that process we were able to recreate the issue and correct it very simply. In all these failure investigations you end up spending far more time proving what it wasn’t than what it was. We were able to prove what it was very very quickly, and then were able to spend a lot more time giving ourselves comfort and going down every single rabbit hole and making sure that there were no other contributing factors and that we really understood the issue.

Sometimes with these things you’ll see a shiny thing and grab a hold of it and think that was it, but it wasn’t really it in the first place. But we were able to very confidently solve the problem, and I think it probably was the quickest return to flight in history, so that’s true testament to the team, the systems and the vehicle, that we were able to get back on the pad quickly.

So the Photon spacecraft will be used for the mission to the Moon next year, and then another adaptation of it will be used for the Venus mission. Are they drastic changes?

No. To be honest with you the spacecraft should be pretty much identical. That was the point, when we first won that NASA mission I said to the team, ‘right, let’s build one to go to the Moon, but at the same time lets build one that will go to Venus.' So really, there’s enough energy in the spacecraft in its current form, enough power, and enough communication that we’re really not having to re-architect the spacecraft at all. We developed a high-energy interplanetary spacecraft bus, and whether it is the Moon or Venus it really doesn’t make any difference.

Awesome. Thank you and good luck.