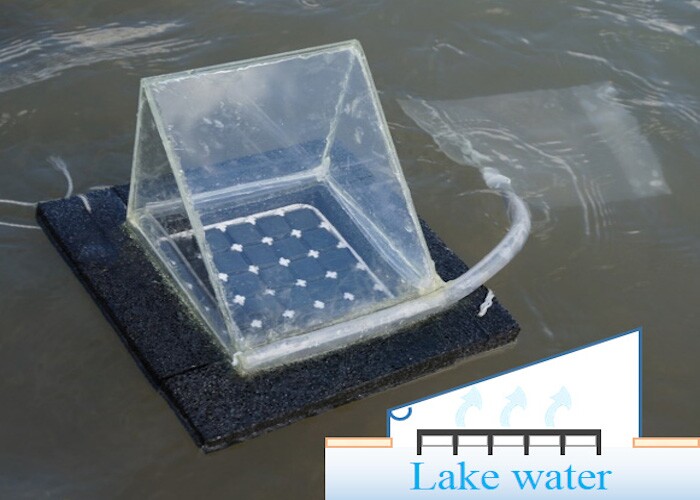

In areas where clean water isn't easily accessible, solar stills can help purify available water that might be dirty or salty. These devices absorb heat from sunlight and use it to evaporate water, leaving behind contaminants and reforming as a liquid in a separate container, and although they work, they can be relatively expensive and inefficient. Researchers have now developed a new type of solar still using carbon-coated paper that they say is cheaper and more than twice as efficient as existing devices.

Solar stills can be live-saving devices for people in developing countries or disaster-affected areas, but there's room for improvement according to the team made up of members from the University at Buffalo (UB), China's Fudan University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"People lacking adequate drinking water have employed solar stills for years, however, these devices are inefficient," says Haomin Song, a co-author of the study. "For example, many devices lose valuable heat energy due to heating the bulk liquid during the evaporation process. Meanwhile, systems that require optical concentrators, such as mirrors and lenses, to concentrate the sunlight are costly."

To overcome these issues, the researchers built their own version of the device. The "solar vapor generator," as they call it, is about the size of a mini-fridge and is made of expanded polystyrene foam and a porous, hydrophilic paper coated in carbon black. By floating the device on a body of water, the carbon black absorbs sunlight, to heat and evaporate the water absorbed by the paper.

Rather than heating the bulk of a body of water, the new device focuses its energy on just the surface water, which evaporated at 44° C (111° F). That allows the still to reach a reported efficiency of 88 percent, which the team believes is a record for thermal efficiency. As a result, the device could produce between 3 and 10 liters (0.8 and 2.6 US gal) of purified water per day, compared to the 1 to 5 liters (0.3 to 1.3 US gal) per day possible with most commercial stills of comparable size currently available.

"Using extremely low-cost materials, we have been able to create a system that makes near maximum use of the solar energy during evaporation," says Qiaoqiang Gan, PhD, associate professor of electrical engineering in the University at Buffalo School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and lead researcher on the study. "At the same time, we are minimizing the amount of heat loss during this process."

Where systems that use lenses and mirrors to concentrate the sunlight can cost upwards of US$200 per square meter, the team claims that its new device could be put together for around $1.60 per square meter – a much more manageable price tag for people in need.

"The solar still we are developing would be ideal for small communities, allowing people to generate their own drinking water much like they generate their own power via solar panels on their house roof," says Zhejun Liu, co-author of the study.

The research was published in the journal Global Challenges.

Source: University at Buffalo