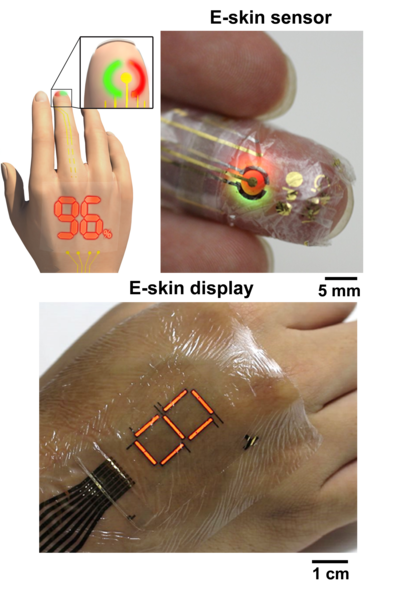

From displays that curve to screens that swerve, flexible electronics is fast developing area of technology that promises to put a new twist on the way we absorb information. Bending televisions are an early example of this being adapted to the consumer world, and if a team of Japanese researchers has its way electronic skin (e-skin) won't be all that far behind. The team's new durable, flexing OLED display prototype is less than one quarter the thickness of Saran wrap and can be worn on the skin to display blood-oxygen levels, with the developers working to afford it other health-monitoring abilities, too.

Smartphones, smartwatches, and even smart rings have offered us new platforms with which to view information. But researchers the world over are working towards a future where you won't need to lift a finger in order to peer into digital realm. The Skinput prototype from 2010 is an example that imagines using human skin as portable displays, and some scientists are even working on haptic feedback for such systems.

Developing e-skin that is thin and flexible enough to be worn comfortably, yet durable enough to maintain its functionality presents a difficult balancing act. Many examples of e-skin developed thus far have been built on millimeter-scale glass or plastic substrates, compromising their flexibility, while e-skins made on the micrometer scale have not proven stable enough to keep working beyond a few hours. But scientists at the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Engineering claim to have overcome these challenges, producing a three micrometer-thick display that can retain its functionality for several days.

The key to their approach is a protective film less than two micrometers thick that shields the display from oxygen and water vapor in the air. The researchers fashioned this protective layer out of alternating layers of silicon oxynitrite and a polymer called parylene. Inside, they then attached transparent indium tin oxide electrodes to a very thin substrate, along with organic photodetectors and polymer light-emitting diodes (PLEDs), claimed to be six times more efficient than previously developed ultrathin PLEDs.

The resulting e-skin is three micrometers thick in total and has just the right amount of give to withstand natural movements when applied to the skin. The team demonstrated the device's functionality by combining red and green PLEDs with a photodetector to track and display blood oxygen levels. But like other flexible, skin-worn electronics that monitor things like bed sores, dry skin and cardiovascular health, the team is hoping to expand its functionality to serve a number of health-related purposes.

"What would the world be like if we had displays that could adhere to our bodies and even show our emotions or level of stress or unease?" says Professor Takao Someya, leader of the research. "In addition to not having to carry a device with us at all times, they might enhance the way we interact with those around us or add a whole new dimension to how we communicate."

The research was published in the journal Science Advances.

Source: University of Tokyo