How do you protect hypersonic vehicles from the high temperatures of over 2,200 °C (4,000 °F) encountered when flying in excess of Mach 5? According to the RTX Technology Research Center, the answer is to make them sweat.

Hypersonic flight holds the promise of revolutionizing aeronautics to a degree not seen since the breaking of the sound barrier in 1947. However, it turns out that going from supersonic to hypersonic is a lot more challenging than going from subsonic to supersonic.

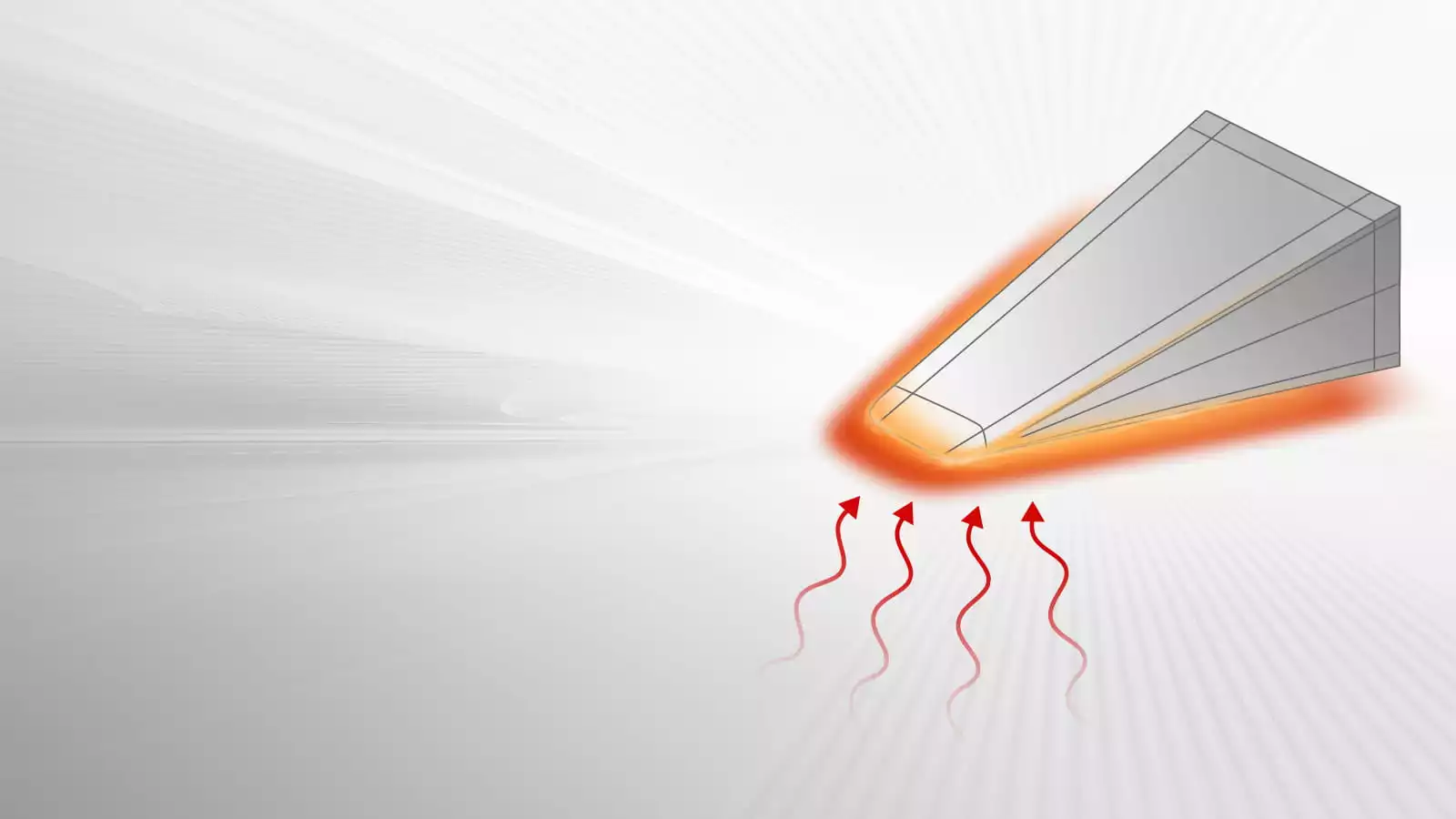

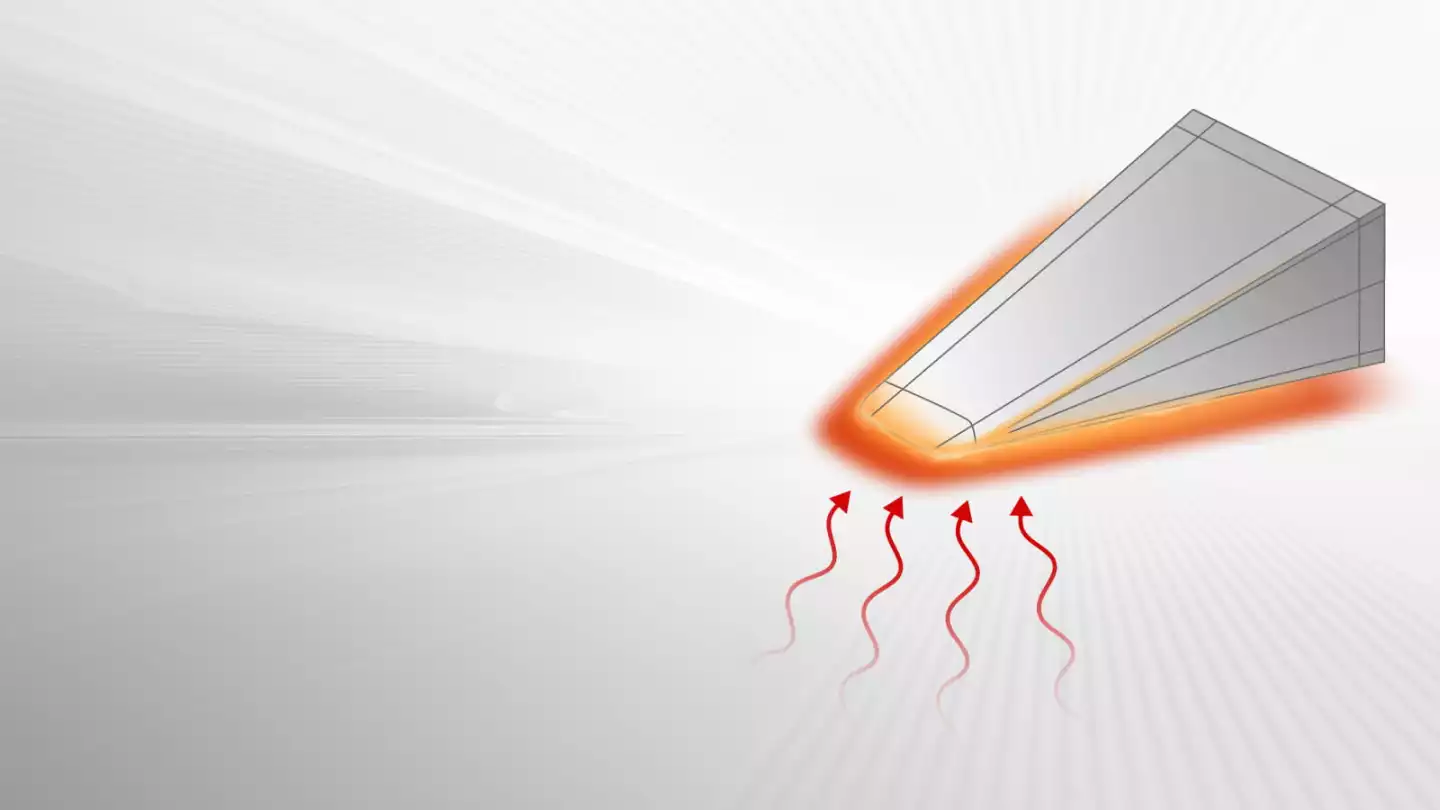

One of the biggest challenges is the tremendous heat generated by a body flying in excess of five times the speed of sound. At these temperatures all but the most exotic of materials melt or become inoperable. This means that the precisely designed and machined lines of a hypersonic vehicle, especially on its leading edges, will quickly round and distort, completely altering the aerodynamics of the vehicle.

The obvious way to avoid this is to cool the outer skin of the vehicle. Unfortunately, with conventional systems, this means adding weight and complexity that engineers aren't particularly fond of.

As an alternative, under a DARPA contract, RTX is looking at cooling hypersonic craft using the same mechanism we use to beat the heat – sweating.

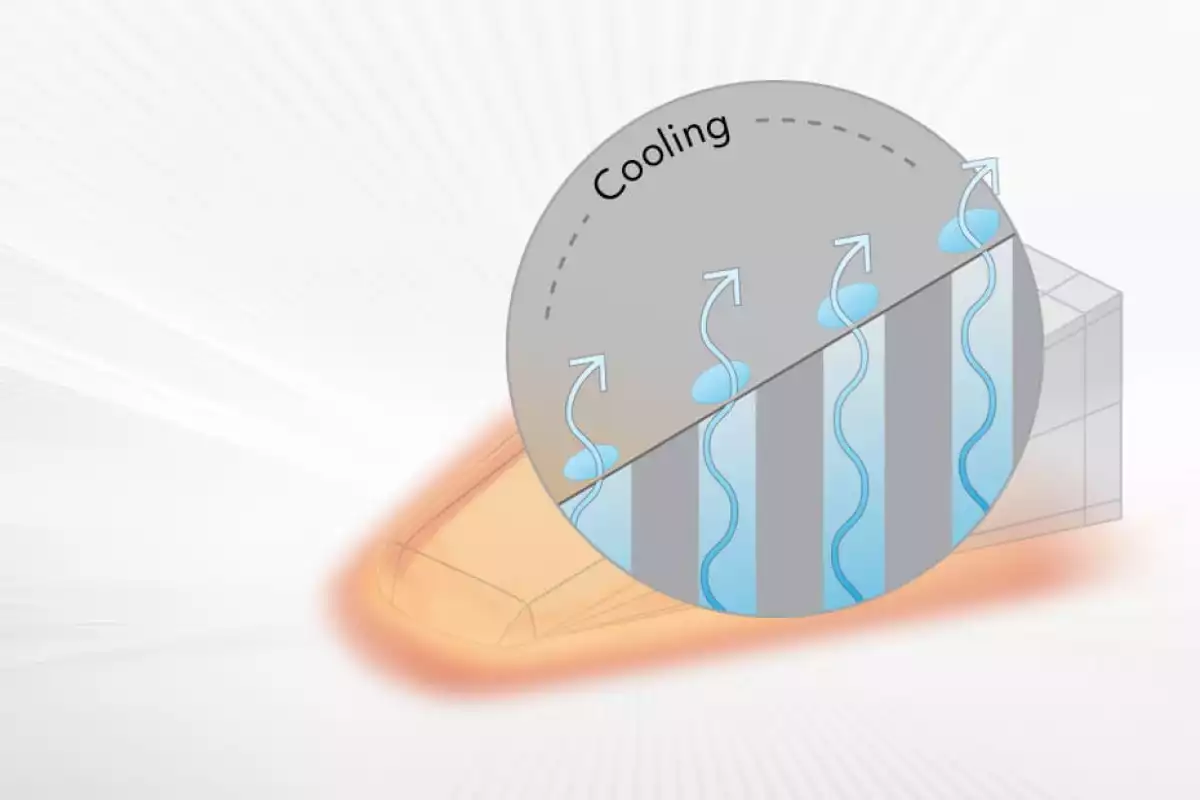

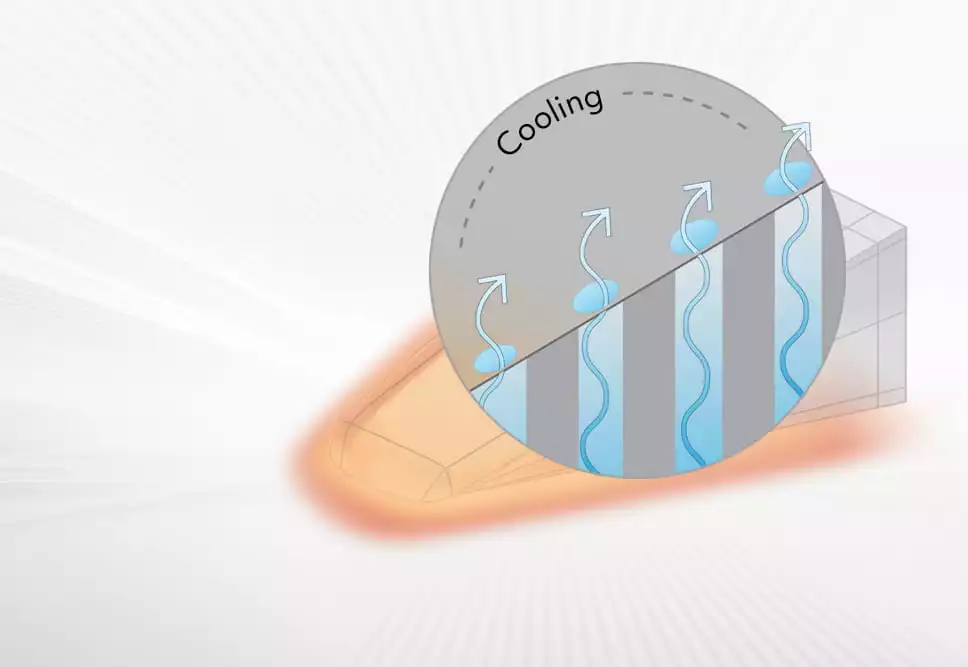

The idea is that the leading edges of a hypersonic vehicle would incorporate a network of micro-channels feeding a liquid to the surface of the skin in a manner similar to human sweat glands. As the liquid reaches the surface, it evaporates, carrying away heat. In this way, the craft can be kept cool enough to maintain its aerodynamics.

According to project team leader John Sharon of the RTX Technology Research Center, predictive modeling and advanced micro-machining was used to create a wedge-shaped test article about the size of a credit card. This was subjected first to a burner rig that was described as a big crème brûlée torch, and then to an electrical arc to heat and expand gasses to high temperatures and speeds that more closely simulated hypersonic flight conditions.

The next step will be to refine the technology by making the sweat channels smaller and enlarging the test article to the scale of a full-size hypersonic vehicle. Should the technique prove successful, it may also be applicable to other problems, like protecting gas turbine blades.

"When you’re flying five-plus times the speed of sound, the temperature can rise very quickly – in a fraction of a second," said Sharon. "The folks on the team involved with modeling did an awesome job estimating how long the test article would survive."

Source: RTX