A team of researchers at Imperial College London has found that attaching an array of cylindrical aluminum studs on top of a solar cell can dramatically improve the amount of light trapped inside its absorbing layer, leading to electrical current gains as high as 22 percent.

In most solar cells, about half of the manufacturing costs are taken up by the absorbing layer alone. This all-important layer is where incoming photons collide with the atoms in the structure and "knock off" electrons, generating a current.

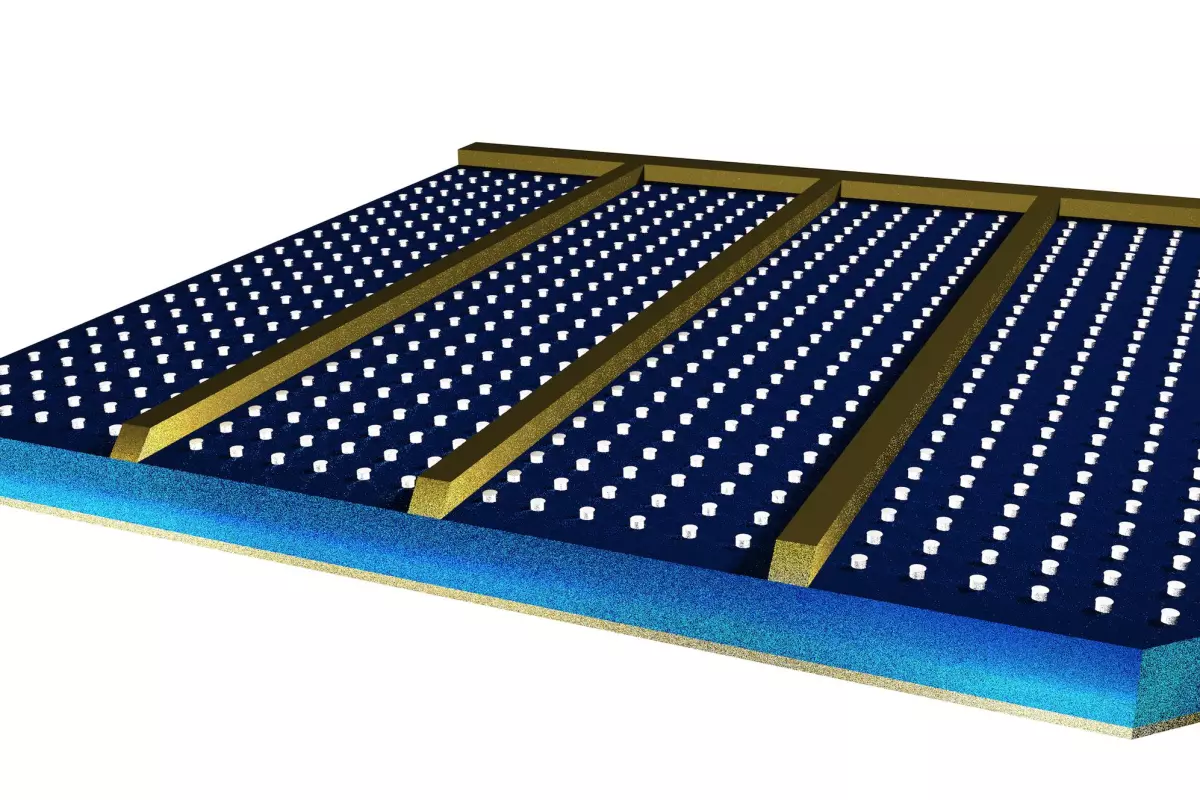

In an effort to reduce manufacturing costs, scientists have been focusing on ways to reduce the thickness of the absorbing layer while keeping efficiencies high. One approach involved depositing arrays of gold and silver studs on top of the solar cells. Since these metals are known to interact strongly with light, the studs were meant to deflect photons at an angle, so that most photons would travel for longer distances within the absorbing layer, and have a greater chance of knocking off an electron.

Unfortunately, that was not the case. A great portion of light was actually absorbed by the studs and, rather than increasing, the overall current produced by the cell actually decreased.

Armed with a better understanding of how the internal structures of different metals interact with light, Dr. Nicholas Hylton and colleagues set out to test a similar array of aluminum nanocylinders.

Besides being cheaper and more abundant than either gold or silver, aluminum is also much better at reflecting and scattering light without absorbing it. Thus, when photons hit the nanoarray, many more are deflected and travel through the absorption region for greater distances, as originally intended.

"The idea with our work is that we're using plasmonic nanostructures to enhance the absorption of light in the semiconductor materials that are used to make solar cells," Hylton tells Gizmag. "In particular we used devices made from gallium arsenide (GaAs) to test the effect of using metal nanostructures and demonstrate enhancements, but the principle could be applied to other types of solar cells like those made from silicon or organic materials."

Comparing the performance of a plasmonic solar cell equipped with the studs to one without the nanostructures, the researchers calculated that the nanocylinders could increase absorption efficiency by up to 22 percent.

The advance could pave the way toward cheaper, thinner, higher-efficiency, perhaps even flexible solar cells.

"In terms of augmenting existing solar panels, this type of technology needs to be integrated into the commercial manufacturing process and depends on our ability to make such tiny metal studs on a large scale," says Hylton. "There are a few technologies available to do this type of task, so it is really a question of how these can be integrated into existing commercial manufacturing processes. That's something we're working on and hope to take forward with industrial partners."

An open-access paper describing the research is available in the journal Nature Scientific Reports.

Source: Imperial College London