They might hold a reputation as one of the ocean's most ruthless predators, but new research has shown that sharks can actually go to some lengths to keep peace in the seas. Scientists used tracking devices to monitor the behavior of different species of coastal sharks, and found that they actually do their hunting in shifts as a way of maintaining a harmonious co-existence.

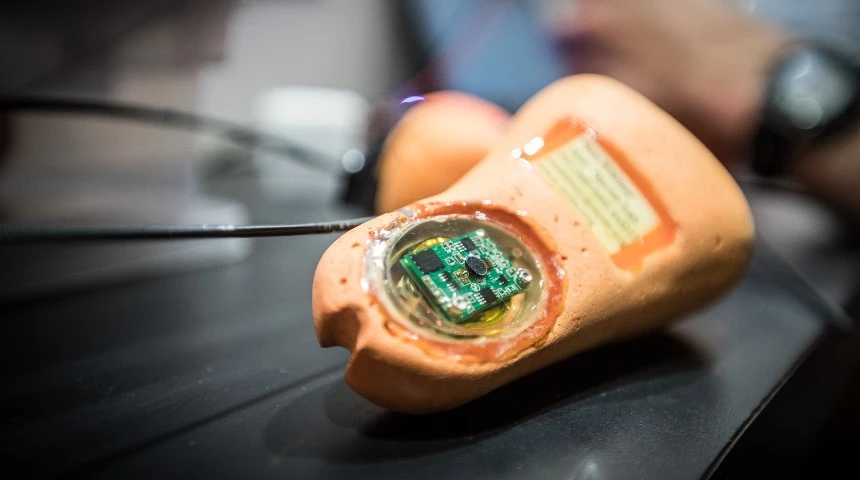

Led by scientists at Australia's Murdoch University, the study focused on six large species in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico, with the cohort including blacktip sharks, bull sharks, sandbar sharks, great hammerhead sharks and scalloped hammerhead sharks. Some 172 free-ranging individuals were tagged with accelerometers, allowing the researchers to follow their movements as they went about their daily business.

This showed that rather than a free-for-all with the different species combing the waters for food whenever they felt like it, these sharks that live near each actually take turns foraging over a 24-hour period, something referred to as "diel temporal partitioning."

“We found bull sharks were most active in early morning hours, tiger sharks during midday, sandbar sharks during the afternoon, blacktip sharks during evening hours and both scalloped and great hammerhead sharks during nighttime hours, the only two species with substantial overlap in timing of peak activity,” says co-lead of the research team, Dr Karissa Lear. “To our knowledge, these results are the first example of diel temporal partitioning in a marine predator guild.”

The scientists believe the animals adopted this approach to hunting as a way of dividing up resources, co-existing in peace and, even, for their own safety.

“This both reduced the competition for food and, for some species, reduces the chances of being preyed upon by larger species,” says co-lead of the research team, Dr Adrian Gleiss. "Indeed, the timing is likely to be at least partially driven by hierarchy – forcing less dominant predators to forage in less optimal periods to avoid those larger sharks.”

Because the hunting behaviors of apex predators like sharks have trickle-down effects on the behavior of other marine species, they play a key role in maintaining healthy and balanced ecosystems. The hope is that research like this that helps us understand the way resources are shared at the top can inform efforts to sustain these types of environments.

“Understanding the mechanisms that allow marine predators to coexist will help us to preserve and restore healthy, predator-rich marine systems,” says Dr Lear.

The research was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Source: Murdoch University