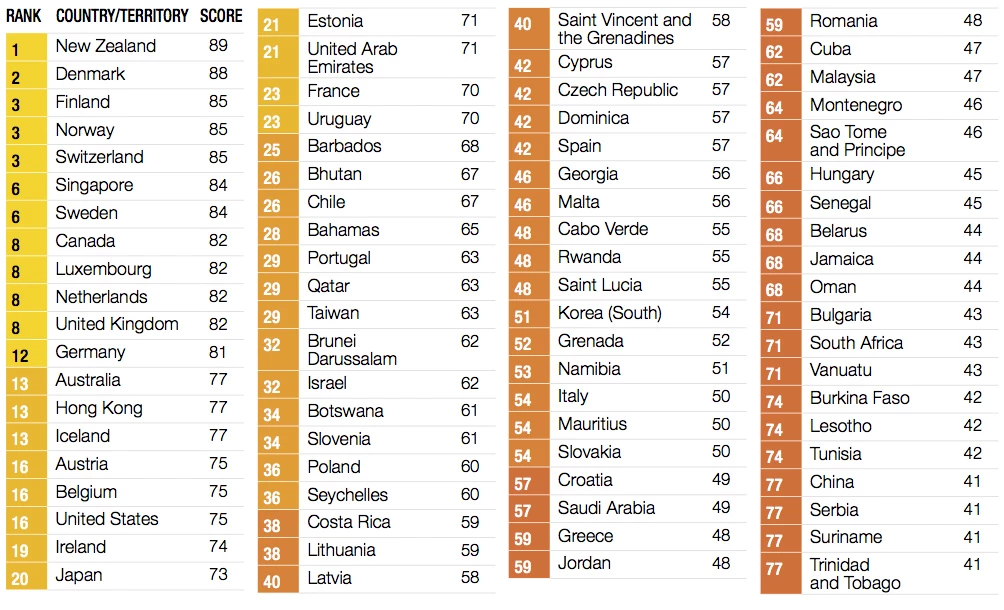

The latest corruption perceptions data covering 2017 was released overnight by Transparency International, making it the 25th year such data has been available. New Atlas has been reporting TI's annual corruption data now for 18 years and sadly, very little has changed.

Twelve months ago in a particularly in-depth analysis of Transparency International (TI) data, we reported that 85 percent of human beings were governed by regimes that score 50 or less, indicating that the integrity of people in authority across the globe was sadly lacking.

Corruption is "the abuse of entrusted power for private gain," and each year since 1995, TI has published a Corruption Perceptions Index that scores the world's nations out of 100 for their public sector honesty, and the same bleak picture we've been seeing now for two decades has emerged once more ... that is, things are getting worse.

By its very nature, corruption is difficult to assess on the basis of hard empirical data. TI's methodology is based on a combination of various independent international surveys aimed at capturing perceptions of those in a position to offer expert assessments of public sector corruption in a given country.

This year the data is more in-depth than ever before, and covers 180 countries, up from the 176 countries covered in last year's survey. Though there are four more countries, only 54 countries scored 50/100 or better, the same number as last year, meaning only 30 percent of countries score 50 or better.

Last year, two countries (New Zealand and Denmark) scored 90 or better, but this year no country scored more than 89, with six of the leading ten countries scoring worse in 2017 than they did in 2016.

We tried hard to look for good news and in an effort to find countries that had significantly reduced corruption over an extended period, we looked at the movement in scores for countries over a five year period.

Those that significantly reduced corruption are Belarus(+13), Greece(+12), South Sudan(+12), Guyana(+10), Latvia(+9), Senegal(+9), North Korea (+9), United Kingdom (+8), Seychelles(+8), Czech Republic(+8), Italy(+8) and Laos(+8). Of those, most countries were starting with a low base, so improvement wasn't difficult in most cases. Three stand-outs were the United Kingdom (now equal 8th), Latvia (now 40th) and the Czech Republic (now 57th), which are now among the 30 percent of countries in the world that score better than 5/10.

As we point out each year, 5/10 might have constituted a pass in a High School arithmetic test, but for an elected government to be so inept at carrying out the will of the electorate, it is quite simply a betrayal of the people.

The countries that have become significantly more corrupt over the last five years are Bahrain (-15), Syria (-12), Hungary (-10), Liberia (-10), Cyprus(-9),Turkey(-9),Australia(-8),Barbados(-8), andSpain(-8).

Most of the countries on that list you'd expect to be there, but the stand-outs are Spain, which has fallen from a score of 65 to 57 over the last five years, and Australia, a country that once prided itself on fair play, but has dropped from a position among the leading countries in the world five years ago, to the same dubious depths of public sector behaviour as the United States of America.

Transparency International's report concludes that "despite attempts to combat corruption around the world, the majority of countries are moving too slowly in their efforts.

"While stemming the tide against corruption takes time, in the last six years many countries have still made little to no progress. Even more alarming, further analysis of the index results indicates that countries with the lowest protections for press and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) also tend to have the worst rates of corruption."

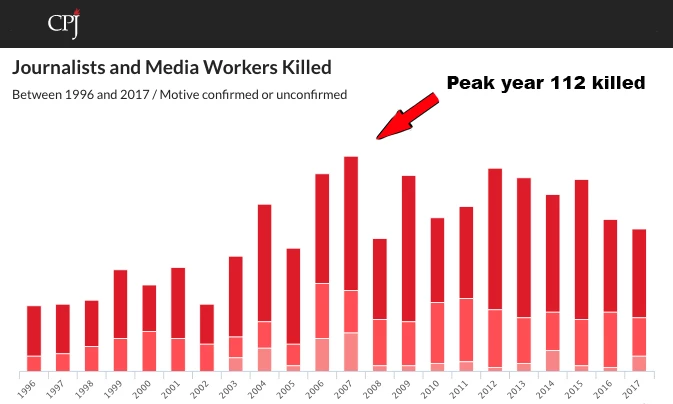

Every week a journalist is killed in a highly corrupt country

Transparency International always seeks to find relevant correlations with its data and one of the key findings this year has been the relationship it has found between corruption levels, the protection of journalistic freedoms and engagement of civil society, finding that almost all journalists killed since 2012 were killed in corrupt countries.

"No activist or reporter should have to fear for their lives when speaking out against corruption," said Patricia Moreira, Managing Director of Transparency International. "Given current crackdowns on both civil society and the media worldwide, we need to do more to protect those who speak up."

Incorporating data from the Committee to Protect Journalists, TI has shown that over the last six years, more than 90 percent of those journalists killed were killed in countries that score 45 or less on the Corruption Perceptions Index. Hence, for the last six years, every week at least one journalist has been killed in a country that is highly corrupt, and invariably, justice is not served.

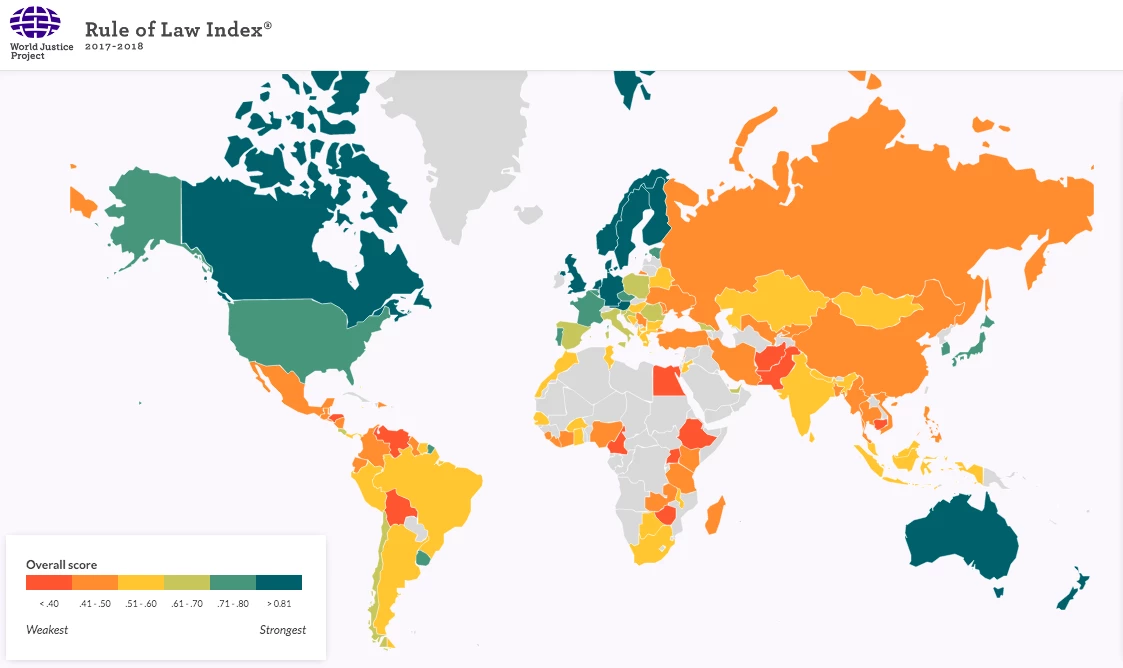

Corruption linked to shrinking space for civil society

Transparency International also found a strong negative correlation between corruption levels and the freedom with which civic organizations are able to operate and influence public policy. The analysis incorporated data from the World Justice Project (above).

"Smear campaigns, harassment, lawsuits and bureaucratic red tape are all tools used by certain governments in an effort to quiet those who drive anti-corruption efforts," said Moreira. "We're calling on those governments that hide behind restrictive laws to roll them back immediately and allow for greater civic participation.

"Hungary, which saw a 10-point decrease in the index over the last six years, moving from 55 in 2012 to 45 in 2017, is one of the most alarming examples of shrinking civil society space in Eastern Europe. If enacted, recent draft legislation in Hungary threatens to restrict NGOs and revoke their charitable status. This would have disastrous implications for many civil society groups already experiencing the constraining effects of a previous law that stigmatizes NGOs based on their funding structures."

"CPI results correlate not only with the attacks on press freedom and the reduction of space for civil society organizations," said Delia Ferreira Rubio, chair of Transparency International. "High levels of corruption also correlate with weak rule of law, lack of access to information, governmental control over social media and reduced citizens' participation. In fact, what is at stake is the very essence of democracy and freedom."

Source: Transparency International