Some historic aircraft seem like a barrel for holding superlatives. One of these, the H-4 Hercules, goes one better because it's also at the center of one of the strangest stories involving possibly the 20th century's strangest man – Howard Hughes.

In 1942, the United States had entered the Second World War and was facing the daunting problem of how to move massive amounts of men, munitions, and supplies across the Atlantic Ocean to Britain in the face of Germany's all-out U-boat offensive to sink as much Allied shipping as possible.

To counter this, construction magnate turned shipbuilder Henry J. Kaiser proposed to the US government the building of a new class of seaplane bigger than anything previously conceived that would essentially be an airborne freighter. An aircraft that could carry 150,000 lb (68,000 kg), 750 fully equipped troops, or two 30-ton M4 Sherman tanks across the Atlantic sounded insane even in 1942, but in a short time Kaiser went from a man who knew nothing about shipbuilding to cranking out Liberty and Victory freighters every 45 days (sometimes in under five days), so he was taken seriously.

To gain the needed expertise in designing and building such an aircraft, Kaiser went into partnership with Howard Hughes, who was already famous for his exploits in aviation, film making, and a private life that was so eccentric that Orson Welles turned down using Hughes as his model for the character of Citizen Kane in favor of the more believable William Randolph Hearst.

It wasn't a long partnership – at least, not in full. Very quickly, Hughes and the Hughes Aircraft company, with characteristic enthusiasm, took over the entire project and left Kaiser on the sidelines more or less as an astonished spectator.

From the get go, things went into the weird zone. Because there was a shortage of strategic materials and the HK-4 (later the H-4) Hercules was a low priority project, Hughes and company weren't allowed to use metal to build the plane. Instead, they had to use wood as much as possible.

It's for this reason that the H-4 Hercules is better known to the world as the Spruce Goose, though at the time it was also called the Flying Lumberyard by its critics and the Birch Bitch by Hughes Aircraft mechanics.

The latter may not be the most polite name, but it was the most accurate because the H-4 was made of birch, not spruce. The fact that what was for a very long time the largest aircraft ever built was made of wood is common knowledge, but that simple statement of fact covers a tremendous amount of technological innovation.

More accurately, the H-4 was built out of a highly advanced kind of laminated Duramold plywood shaped on special forms and made by bonding several plies of birch veneer with a urea-formaldehyde glue. These plies were sealed together under heat and pressure and cured using high-frequency electronic radio waves. The outer surfaces were then sanded, covered with rice paper, coated, painted, and polished to a smooth hydrodynamic finish.

Even the heavy support beams and spars that made up the skeleton of the craft were made of laminates because it wasn't possible to find the right wood in solid form or inspect it properly for flaws or rot. All this meant new tools and dies had to be fabricated and new glues developed.

A plane that was three times larger than anything previous required a lot of new ideas and some out-of-the-box thinking and Howard Hughes encouraged that. He also produced continuous frustration for his partners, his company executives, and the US government as the project began to reflect his eccentric personality. Unlike many tech entrepreneurs, Hughes took a personal interest in every aspect of design and construction to the point where he personally flew hundreds of hours in a specially modified seaplane to test new design ideas.

He was also aggravating to an incredible degree – not the least because he regarded the Hughes Tool Company as his personal piggy bank to finance his latest fancy. He had very little contact with the top people in his organization and when he did it was usually in the form of phone calls in the wee hours of the morning. He also had long discussions with engineers, designers, and workers as he indulged in a time-consuming quest for perfection in every aspect of the project, which often resulted in workers far down the food chain being tasked with giving instructions to their superiors.

"He came to the [Hercules] at night – he always worked at night," said John Glenn, the last surviving member of the H-4 flight crew, who passed away in 2012. "This man was unbelievable as far as mechanical engineering went. He would sit there and run those engines for hours on end. Feel them out and see how they were. He knew that airplane before he flew it backside and frontside. He was unbelievable."

Hughes also took a finicky interest in not only the engines but even the instrument panels, spending many hours on getting every instrument exactly where he wanted it and to heck with what the electricians thought about the wiring.

Meanwhile, all of this work was in the eye of a political hurricane, with Hughes in constant battle with opponents in Washington as he lobbied, cajoled, badgered, and indulged in some rather dirty tactics in order to keep the project from being cancelled for being behind time, unneeded, or made of the wrong material. Not to mention fighting congressional pressure on Hughes to merge his TWA airlines with Pan Am and miscellaneous accusations that embroiled Hughes in an ongoing Senate investigation that produced a famous quote as he gave testimony after the war ended and still no plane had materialized and its reason for existing was now gone.

"The Hercules was a monumental undertaking," said an angry Hughes. "It is the largest aircraft ever built. It is over five stories tall with a wingspan longer than a football field. That's more than a city block. Now, I put the sweat of my life into this thing. I have my reputation all rolled up in it and I have stated several times that if it's a failure I'll probably leave this country and never come back. And I mean it!"

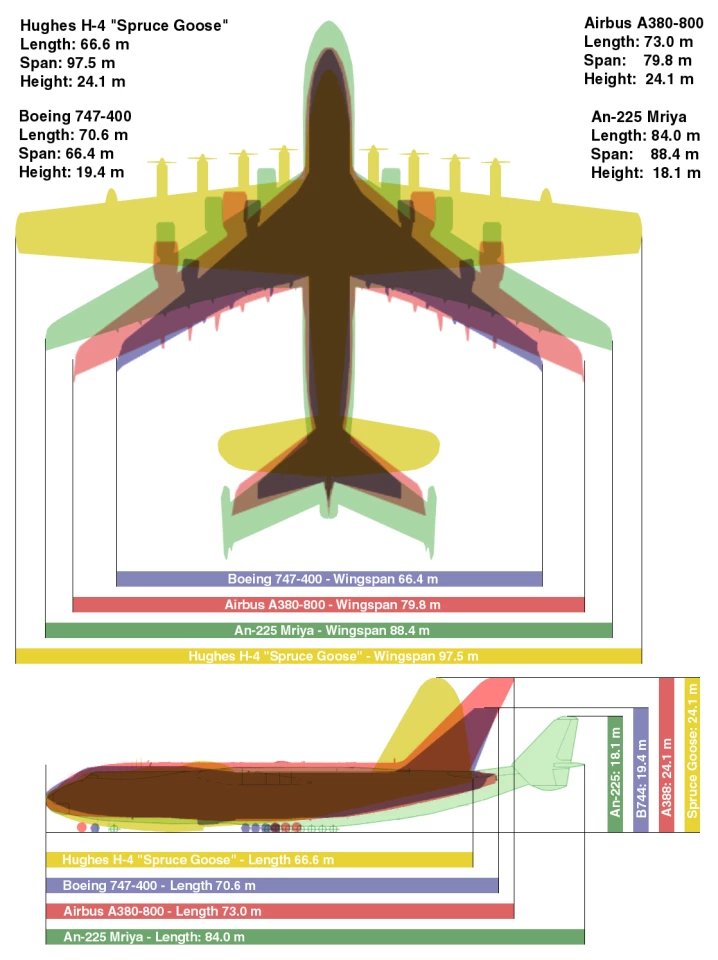

The climax came on November 2, 1947 when the Spruce Goose floated out into the waters off Long Beach, California in the middle of a deliberate Hughes media blitz. The aircraft was a tremendous sight and still is today. With a smooth metallic sheen that definitely didn't look like wood, it was 218 ft 8 in (66.65 m) long, had a wingspan of 319 ft 11 in (97.51 m) and stood 79 ft 4 in (24.18 m) at the rudder, with an empty weight of 250,000 lb (113,398 kg).

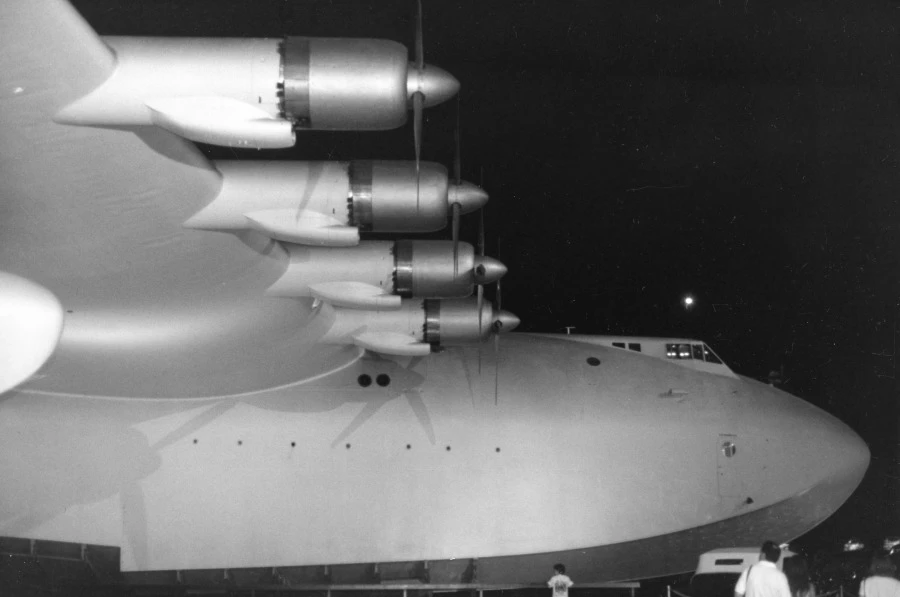

Along the massive wings were eight Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major 28-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engines punching 3,000 hp (2,200 kW) each to turn the four-bladed Hamilton Standard propellers that spanned 17 ft 2 in (5.23 m), yet were dwarfed by the plane itself. The plane was so large that it was possible for engineers to walk inside the wing and service the engines in flight. The control surfaces were so massive that a bespoke powered hydraulic system was needed for the pilot to move them. There was even a new high-voltage wiring system to allow for thinner, lighter wiring to save weight.

With members of the press aboard, Hughes took the pilot's seat of the Spruce Goose. This was more than ego. He knew more about the aircraft than anyone and was the most experienced at handling it. The reporters were told that this was just a preliminary taxi test, with the first flight still in the future.

That's not what happened.

After a few taxiing maneuvers, Hughes suddenly opened the throttles, reached a speed of 70 knots (80 mph, 129 km/h), and the giant aircraft lifted into the air, reaching a top speed of 117 knots (135 mph, 217 km/h) as it flew for one mile (1.6 km) over 26 seconds. Top altitude: 70 ft (21 m).

Whether Hughes planned this, decided then that it was a way of getting back at those who said it would never fly, or it was just a spur of the moment decision based on favorable conditions is something Hughes never revealed and we will probably never know.

The end of the story is equally strange. In the wake of its first and only flight, in 1948, Hughes, after purchasing the RKO film studio, spent US$1.75 million to build a humidity-controlled hangar for the sole purpose of holding the H-4 Hercules. There the Spruce Goose sat under 24-hour guard as a staff 300, reduced to 50 in 1962, kept the plane in flyable condition, even firing up the engines once a week until a special turning apparatus was invented. Through flood, earthquake, and subsidence, the Goose was coddled like a pedigree bird at a cost of US$1 million a year until Hughes died in 1976 after years of decline into Las Vegas penthouse seclusion and bizarre eccentricity.

There followed years of legal wrangling because Hughes left no will and there was an argument as to who actually owned the H-4. After much discussion about what to do with the historic aircraft, fears that it would be broken up and its parts sent to museums, and a brief stint in a special geodome next to the landlocked RMS Queen Mary in California, it now resides intact and on display at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.

In the meantime, its records for largest aircraft, longest wingspan, and others have fallen to newer machines. However, just as, to paraphrase Sydney Greenstreet's Fat Man, who said there is only one Maltese Falcon, there is and only ever will be one Spruce Goose.