Researchers have tracked muscle contractions in a bird's vocal tract, and reconstructed the song it was silently singing in its sleep. The resulting audio is a very specific call, allowing the team to figure out what the bird's dream was about.

When birds sleep, the part of their brains dedicated to daytime singing remains active, showing patterns that resemble those produced while awake. Researchers from the University of Buenos Aires (UBA) previously demonstrated that these brain patterns activate a bird’s vocal muscles, enabling them to silently ‘replay’ a song during sleep.

But, until now, it hasn’t been possible to map how that nocturnal activity gets processed. In their new study, the UBA researchers turned the vocal muscle movements made during avian dreaming into synthetic songs.

“Dreams are one of the most intimate and elusive parts of our existence,” said Gabriel Mindlin, a specialist in the physical mechanisms behind birdsong and corresponding author of the study. “Knowing that we share this with such a distant species is very moving. And the possibility of entering the mind of a dreaming bird – listening to how that dream sounds – is a temptation impossible to resist.”

A bird’s vocal sounds are made by a unique organ only they possess, the syrinx. Located at the base of the windpipe (trachea), passing air causes some or all of the organ’s walls to vibrate, while a surrounding air sac acts like a resonating chamber. The pitch of the sound produced depends on the tension surrounding muscles exert on the syrinx and the airways.

The researchers chose the great kiskadee for their study, as it was the species they’d used in their previous research. Common throughout Middle and South America, the boisterous and aggressive bird is known for its three-syllable call – in fact, its “kis-ka-dee” sound is how it got its name. When defending its territory, the great kiskadee produces a distinct vocalization pattern – a ‘trill’ of short syllables – accompanied by raising its crest of head feathers.

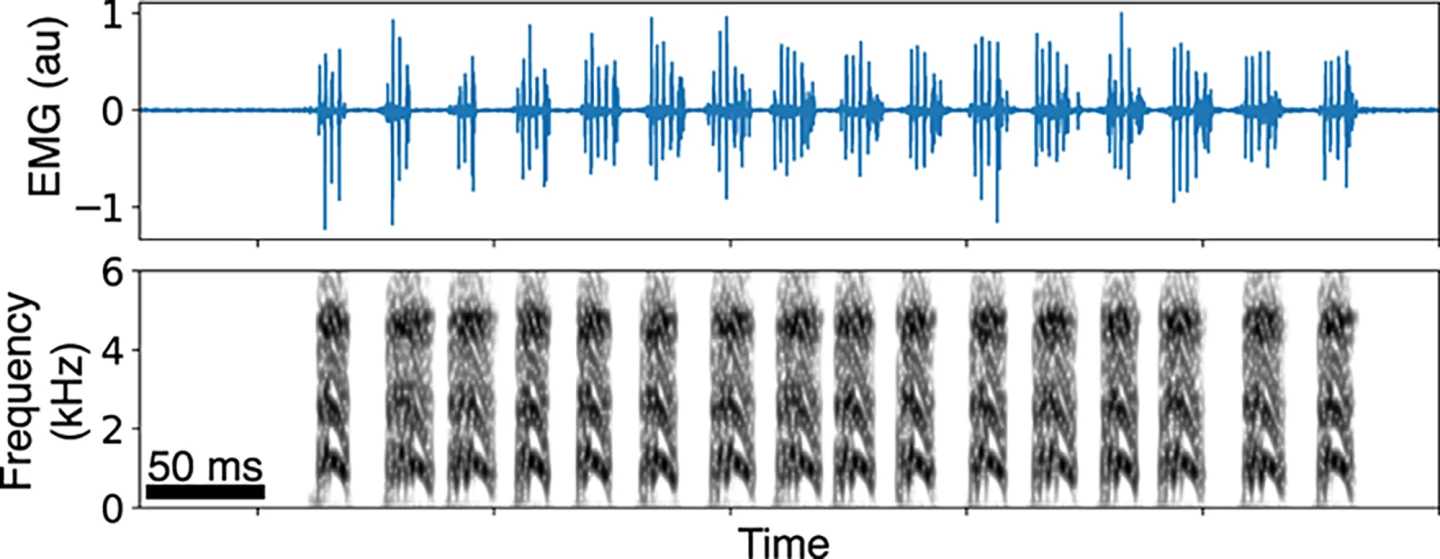

Custom-made electromyography (EMG) electrodes were implanted in the birds to measure the muscle response and electrical activity in the obliquus ventralis muscle, the most prominent muscle producing the kiskadee’s birdsong. EMG and birdsong audio were recorded simultaneously while the birds were awake and asleep. An existing dynamical systems model of the kiskadee’s sound production mechanism was used to translate the information into synthetic songs. In basic terms, a dynamical systems model breaks down what occurs in the syrinx when sound is produced into a series of mathematical equations.

“During the past 20 years, I’ve worked on the physics of birdsong and how to translate muscular information into song,” Midlin said. “In this way, we can use the muscle activity patterns as time-dependent parameters of a model of birdsong production and synthesize the corresponding song.”

Analyzing muscular activity during sleep revealed consistent activity patterns corresponding to the trills produced by kiskadees during daytime territorial fights. Interestingly, the ‘dreaming trills’ were associated with raised head feathers, the same as during the daytime. The researchers created a synthetic version of one of the trills from the data they’d collected.

“I felt great empathy imagining that solitary bird recreating a territorial dispute in its dream,” Midlin said. “We have more in common with other species that we usually recognize.”

The researchers say that their study has provided “a unique window into the avian brain” and that using dynamical biomechanics models to translate signals into behavior could be extended to other species.

“In other words, in this work, we have shown how physical models can be used to listen to what a bird is dreaming,” they said.

The study was published in the journal Chaos.

Source: AIP Publishing