The first known cases of accidental choking have been discovered, dating back 150 million years, when some opportunistic fish got more than they bargained for picking off algae and slime from dead squid-like creatures. Lucky for them, the fish are no longer around to learn about the embarrassing fate of their ambitious ancestors.

Researchers from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU Munich) have uncovered this ancient tale of instinct gone wrong through analysis of fossils of Tharsis, an extinct genus of ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii). The common fish, classed as micro-carnivores with tiny teeth, most likely survived on a steady diet of zooplankton or other small organisms, using suction feeding that required little breakdown of their small meals. At the time, the genus was one of the largest in the Solnhofen Archipelago, making up around 26% of the entire fish fauna.

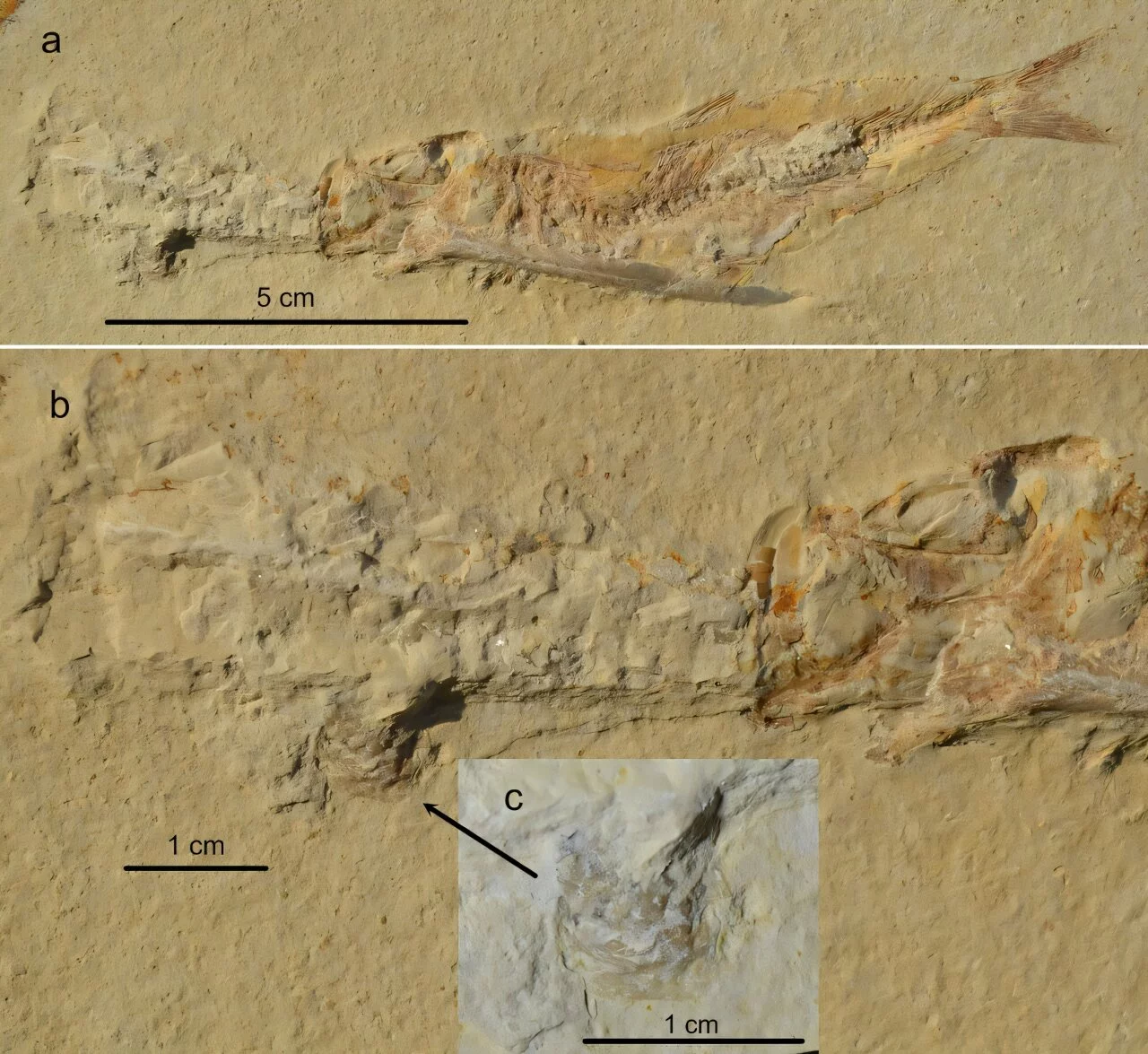

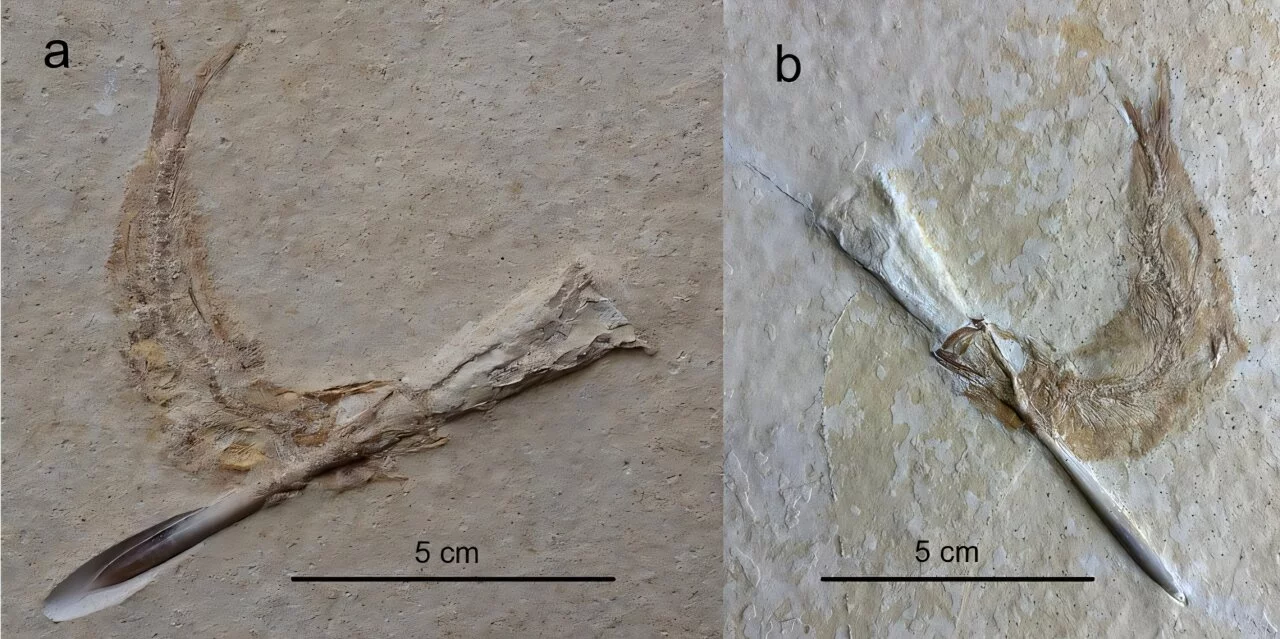

However, some curious fossils have told a different story of how some Tharsis literally bit off more than they could chew. In the fossils sourced from the Solnhofen lagoons in southern Europe – a series of shallow bodies of water that existed during the Late Jurassic period – the scientists observed that the fish remains were intertwined with rostra, or the internal structures, of extinct squid-like belemnite Hibolithes. The soft-bodied belemnites appeared to be trapped in the mouths and gills of the fish.

What's more, the fossils were so well preserved that the belemnites also had remnants of epibionts attached to their bodies, like oysters. It was the existence of these freeloading organisms that indicated to the researchers that the belemnites were long deceased, as bivalve larvae won't attach to living, free-moving cephalopod tissue. As such, the belemnite body parts were thought to be floating in the lagoon's water column for some time before a Tharsis individual made its deadly choice.

Belemnites were also rare in the Solnhofen Plattenkalk basins, where the fish fossils were sourced, as the low-oxygen lagoons were not fit habitats for such cephalopods. But instead of sinking to the bottom after death, the carcasses would have floated into the waters shared by the Tharsis fish and kept buoyant due to their gas-filled phragmocone chamber.

"The evidence suggests that the subadult Tharsis specimens have been nibbling and sucking microbial mats or soft tissue remnants off a floating, dead belemnite and accidentally sucked in the 'bulb' at the end of the hastate rostrum," the researchers noted. "Once this happened, the belemnite proved to be a deadly trap due to its peculiar shape and sheer size. Even though the fish tried to pass the obstructive item through its gills, there was no way of getting rid of it, leading to death by suffocation."

The fascinating fossils show that the pointy rostrum of the belemnite remains had entered the fish through the mouth, and because of the animal's bullet-like shape, quickly filled the mouth of the Tharsis. The fish then, choking on the convenient snack, would have attempted to push the belemnite tissue out through the gills, while the inflated phragmocone remained in the mouth cavity, suffocating the animal in the process.

"The fully open mouth of the subadult Tharsis specimens described here is roughly capable of swallowing prey about 1 cm in diameter," the researchers wrote. "So, if the Tharsis swallows the 'bulb' of the belemnite rostrum, it can continue sucking it in until the phragmocone widens and is about 1 cm in diameter, but no further, because then it will become too wide for its mouth. Once the first maximum of the rostrum’s 'bulb' was overcome, it was probably easier to go further in than out. In addition, most fishes with small teeth capable of suction feeding like Tharsis cannot bite off prey or spit out what is far inside."

The scientists believe that it wasn't a case of the fish having "eyes too big for their belly," but they were most likely trying to nibble slime or algae off the belemnite carcass and accidentally ended up with the rostrum wedged in their mouths – the point of no return.

Why this sorry tale of a tragic meal time is significant is that such a detailed story of death is rare in fossils, and it's the first known case of this kind of choking death in vertebrates. It also shows how – much like today when marine species ingest plastics mistaken as food – animal instinct can fatally backfire.

"Consequently, one would not expect an encounter of belemnites as prey for Tharsis – and yet, there are several such incidents documented in the fossil record, which – such is the nature of the fossil record – ended deadly for the presumed predator," added the researchers.

So while their untimely demise happened within minutes 150 million years ago, thanks to this discovery their tales of mealtime misadventure are now permanently etched in the history books.

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Source: LMU Munich via Nature