Scientists have discovered how an Australian jumping spider's semi-hydraulics allows it to speed jump long distances with precision while experiencing g-forces higher than those of fighter pilots. Their insights might help robotics research.

Most land animals can jump, and, terrifyingly, so can some spiders. Jumping spiders propel themselves using a distinctive combination of hydraulic pressure and muscular action. So, while the prospect of a jumping spider might be icky, the biomechanics behind it are certainly interesting.

New research by Macquarie University in Sydney has examined the jumping ability of the Australian splendid peacock spider in great detail to better understand the unique semi-hydraulic biomechanics underlying it.

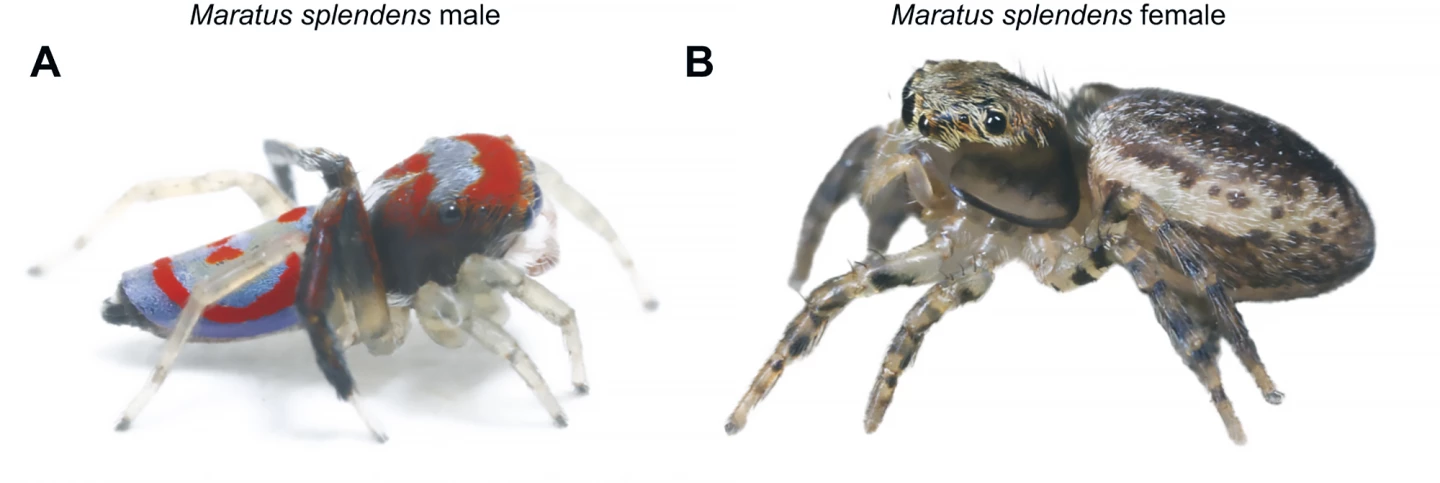

“These spiders are so small you could fit four or five of them on your thumbnail,” said Associate Professor Ajay Narendra from the University’s School of Natural Sciences and the study’s lead and corresponding author. “Males weigh just two milligrams – one of the lightest jumping spiders known – while females are six times heavier.”

Splendid peacock spiders (Maratus splendens) are jumpers. However, spider jumps aren’t muscle- or spring-actuated. While spiders do have flexor (that is, bending) muscles in their legs, they don’t have the extensor muscles required for leg extension and power jumping. Instead, they use an unusual strategy that’s referred to as a “semi-hydraulic locomotion system.” Before a spider jumps, it contracts muscles in its cephalothorax (the fused-together head and thorax of spiders) to push hemolymph, their version of blood, into its legs. The hemolymph builds pressure in the legs, causing them to extend rapidly. When the spider releases the pressure, the legs snap forward, propelling the spider into the air with great force.

Due to their different body sizes and shapes, male and female jumping spiders exhibit different jumping dynamics. Brightly colored male splendid peacocks are smaller than the plain-colored females, whose bodies have to accumulate resources for egg production.

The researchers collected mature adult male and female splendid peacock spiders and placed them on a horizontal take-off platform in a lab maintained at a constant temperature of 24 °C (75.2 °F). A vertical landing platform was placed 4 cm (1.6 in) away from the take-off platform. Individual spiders were recorded jumping from the take-off to the landing platform of their own accord. That is, they weren’t prodded into jumping; it occurred naturally.

“We had the spiders jump across a four-centimeter gap from a take-off platform to a landing platform, which we filmed at 5,000 frames per second using a high-speed camera,” said Macquarie Master of Research student and study co-author Anna Seibel.

After they’d been filmed, the spiders were released back into their natural habitat. The researchers then conducted a manual frame-by-frame analysis of the footage, tracking different body structures and extracting coordinates from which they could reconstruct the jump trajectory. They could also ascertain from the footage how different legs contributed to jumping. By the way, when you look at a male splendid peacock spider, what stands out is its third set of legs.

“The third pair of legs is longer, darker and thicker than the other legs, and has tufts of hair,” said co-author Pranav Joshi, a PhD student studying spider biomechanics. “Males extend these legs and wave them at females during courtship.”

After studying the jump kinetics of 10 male and 12 female spiders, the researchers found that the third and fourth pairs of legs “played a crucial role” in jumping for both sexes. The peacock spiders raised their first two pairs of legs and extended them in front of their bodies. The fourth pair left the take-off platform next, followed a few milliseconds later by the third pair, which were the last legs to leave the ground. These findings suggested that leg three was the “propulsive leg” in male and female splendid peacocks.

The researchers also found that the spiders’ acceleration was the fastest among all known jumping spiders. The male spiders, which are lighter, had significantly shorter take-off times compared to females. On average, male and female spiders experienced the equivalent of 13.03 gs and 12.5 gs, respectively, during take-off, which is higher than any other known jumping spider. By the way, a typical human can handle about 5 gs before losing consciousness. A trained fighter pilot wearing an anti-g suit can withstand up to 8 or 9 gs.

“For animals like us with more rigid bodies, the ability to withstand g-forces is far more limited than for spiders, whose soft and fluid-filled bodies deal with this pressure in a far better way,” Narendra said. “Their low body mass reduces forces acting on their body. This also reduces stress on individual body parts as forces are distributed over their entire body.”

The researchers think their findings could be used to assist robotic development.

“Jumping spiders have [an] exceptional ability to control their jumps to reach specific targets – whether to land on surfaces or to catch small fast-moving insects,” said Narendra. “Robotics researchers are likely to be inspired to build robots based on the semi-hydraulic systems of jumping spiders that have efficient goal-directed movements.”

The study was published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Source: Macquarie University