Scientists in Israel have leveraged commercially available sensors to develop an advanced lie-detection system they say outperforms any other known method. The technology relies on electrodes attached to the face to reveal contorting muscles associated with deception, and could even lead to cameras and software that are able to detect such facial movements on their own.

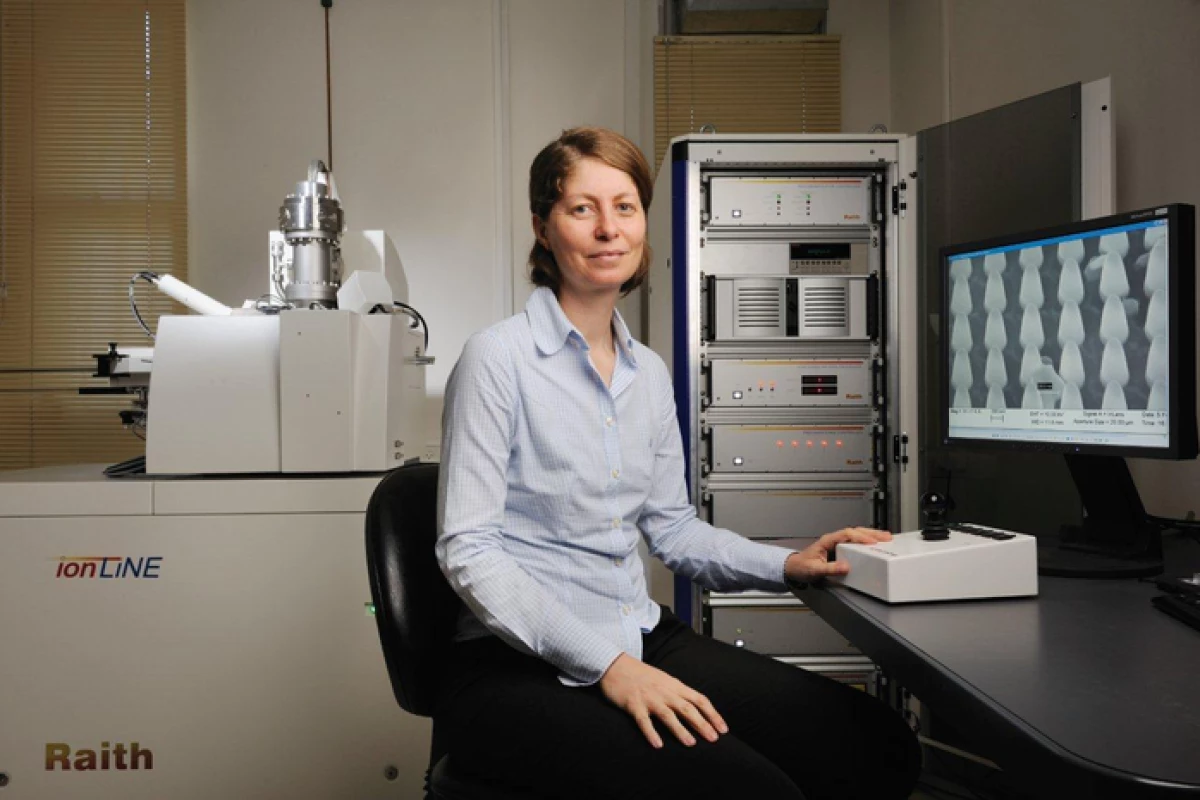

The research carried out by scientists at Tel Aviv University hinges on a sensing technology developed over 15 years by Professor Yael Hanein from the School of Electrical Engineering. This takes the form of stickers containing electrodes that can be placed on the skin to track activity of muscles and nerves, by measuring the electrical signals they put out.

This tech has been commercialized through an Israeli spin-off venture called X-trodes, who market the electrodes as a way of tracking sleep, athletic performance and the detection of neurological diseases. For this new study, the Tel Aviv University researchers investigated how it might be used to reveal when people are telling fibs.

"Many studies have shown that it's almost impossible for us to tell when someone is lying to us," says study author Professor Dino Levy. "Even experts, such as police interrogators, do only a little better than the rest of us. Existing lie detectors are so unreliable that their results are not admissible as evidence in courts of law – because just about anyone can learn how to control their pulse and deceive the machine. Consequently, there is a great need for a more accurate deception-identifying technology. Our study is based on the assumption that facial muscles contort when we lie, and that so far no electrodes have been sensitive enough to measure these contortions."

The team tested this assumption by conducting an experiment where participants where paired up and made to sit opposite one another. One of each pairing was fitted with headphones that played either the word "line" or "tree," with the wearer made to relay one of those words to their partner, either truthfully or deceptively. The partners were unable to detect the lies with any reliability, but the sensing system did so with success.

The system consisted of electrode stickers placed on two groups of facial muscles, the cheek muscles near the lips and the muscles above the eyebrows. The electrical signals were passed onto a machine learning algorithm trained to separate falsehoods from truths, and was able to detect the participants' lies with an "unprecedented" success rate of 73 percent.

"Since this was an initial study, the lie itself was very simple," says Levy. "Usually when we lie in real life, we tell a longer tale which includes both deceptive and truthful components. In our study we had the advantage of knowing what the participants heard through the headsets, and therefore also knowing when they were lying. Thus, using advanced machine learning techniques, we trained our program to identify lies based on EMG (electromyography) signals coming from the electrodes. Applying this method, we achieved an accuracy of 73 percent – not perfect, but much better than any existing technology. Another interesting discovery was that people lie through different facial muscles: some lie with their cheek muscles and others with their eyebrows."

The scientists say these results demonstrate how wearable electrodes can be used to detect lying humans, but imagine a (potentially dystopian) future where they mightn't be required at all. With sophisticated enough video cameras and machine learning algorithms, the team envisions a system that could detect lies simply through analysis high-resolution imagery.

"In the bank, in police interrogations, at the airport, or in online job interviews, high-resolution cameras trained to identify movements of facial muscles will be able to tell truthful statements from lies," says Levy. "Right now, our team's task is to complete the experimental stage, train our algorithms and do away with the electrodes. Once the technology has been perfected, we expect it to have numerous, highly diverse applications."

The research was published in the journal Brain and Behavior.

Source: Tel Aviv University via EurekAlert