Many of the landmines and bombs dropped in Cambodia during the Vietnam War remain unexploded, which is a huge problem that is not easily solved for those tasked with clearing them away. Scientists have developed a new AI-powered tool that could make things a lot easier, with an ability to detect bomb craters through satellite imagery with great accuracy and therefore help reveal where the undetonated devices might remain.

The research was conducted by scientists at Ohio State University, who began with a satellite image of a 100-sq-km (38-sq-mi) area that was the target of carpet bombing by the US in 1973. The team started with computer algorithms originally developed to detect meteor craters on moons and planets, and then trained them to detect the subtle differences between these types of craters and those created by bombs.

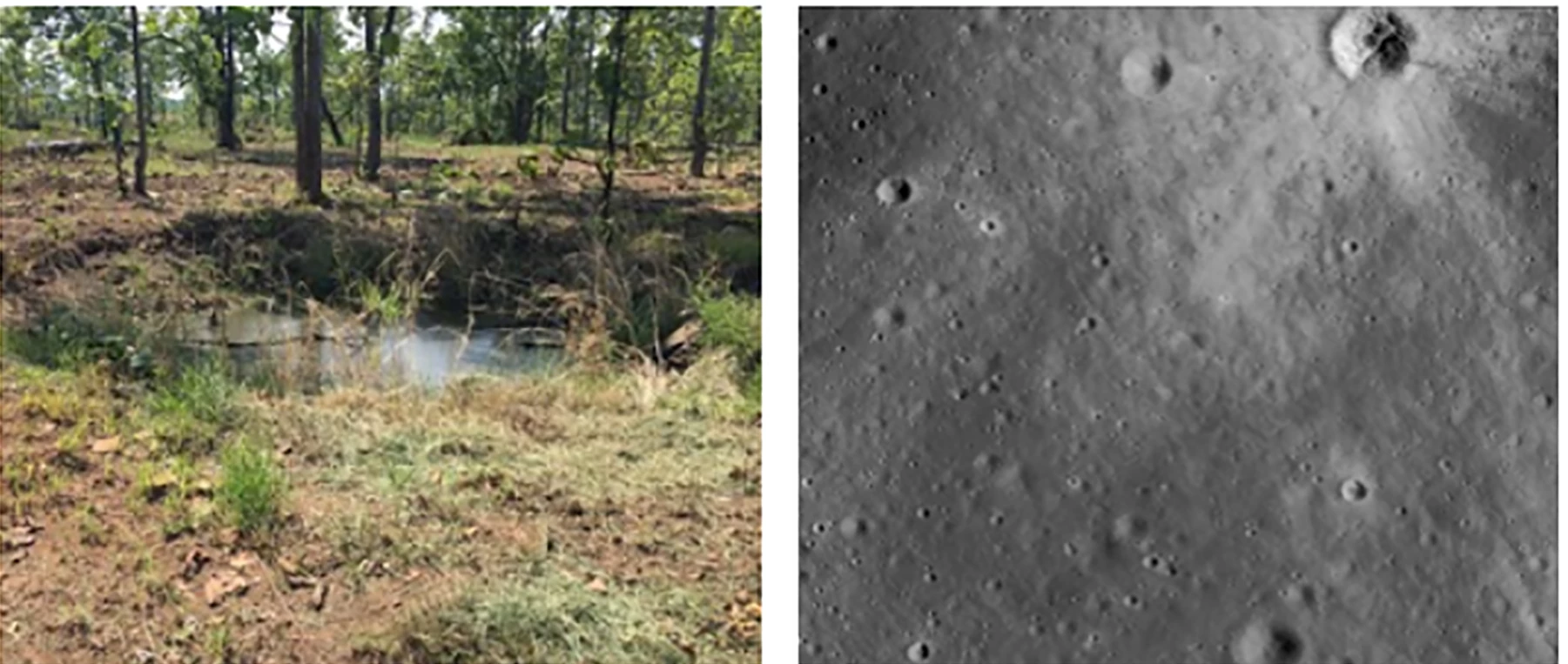

This meant taking into account the different shapes, colors, textures and sizes of bomb craters. This was vital, as things like grass, shrubs and erosion have all changed the face of the bomb craters over the decades since they were created.

Initially, the machine learning algorithm was able to detect 157 out of 177 true bomb craters, an accuracy of 89 percent, although at the same time it identified 1,142 false positives – crater-like features that weren't made by bombs. With further work, the team was able to eliminate 96 percent of these false positives with only a slight compromise on accuracy, with the algorithm still detecting 152 out of 177 craters, an accuracy of 86 percent.

The team says its machine learning algorithm offers an increase in true bomb detection of more than 160 percent. And this could prove a powerful tool in helping to find and clear away those that remain unexploded.

Through declassified military data, the researchers calculated that a total of 3,205 carpet bombs were dropped in the area that they studied. Knowing how many exploded and where, they can then begin to work out how many did not detonate and where they might be. They say that the research revealed there are between roughly 1,400 and 1,600 carpet bombs in the area that remain unexploded.

A lot of the land the team focused on in its research is used for farming, which means there is serious danger for those working in the area. According to the researchers, one person is injured every week from unexploded devices in Cambodia, with more than 64,000 injured or killed since the area was bombed in 1973.

“The process of de-mining is expensive and time-intensive, but our model can help identify the most vulnerable areas that should be de-mined first,” says Erin Lin, assistant professor of political science at Ohio State University.

The research was published in the journal PLOS One.

Source: Ohio State University