Seventy five years ago, the world was introduced to ENIAC, the first ever electronic, programmable, general purpose, digital computer, in a demonstration that not only ushered in the first glimmers of the computer age, but also shaped popular conceptions of the computer that continue to this day.

ENIAC is short for Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, and though it was closer in its basic design to modern computers, it wasn't the first electronic computer. However, its rivals were all either experiments that ended up in dusty obscurity or ultra top secret projects whose existence wasn't made public until the 1970s.

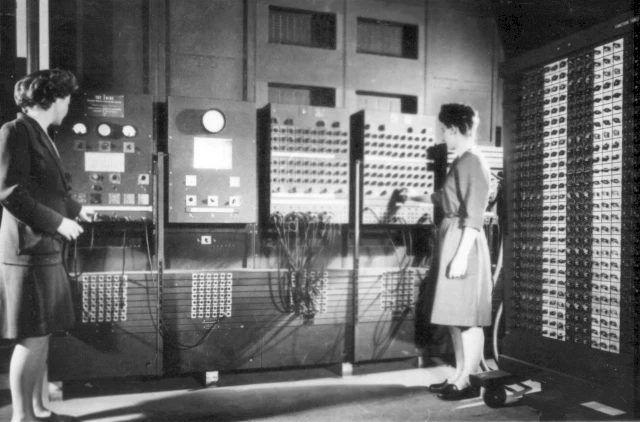

Nevertheless, when ENIAC made its debut before the newsreel cameras in February 1946, it definitely looked the part for what would become the stereotypical giant electronic brain. It cost US$500,000 (about US$7.2 million in 2020 dollars), weighed in at 27 tonnes, stretched in a square U-shape for 80 feet (24 m), covered 1,800 square feet (167 sq m), and gulped down 150 kW of electricity to power its 18,800 radio valves or vacuum tubes.

By today's standards, it would underperform a bargain store pocket calculator, but when it was built, it represented a leap forward in calculating speed of several orders of magnitude.

It started life in 1942 at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering of the University of Pennsylvania with backing by the US Army Ordnance Department and the Ballistic Research Laboratories as part of a project to produce gunnery tables for new artillery being developed for the US effort after joining the Second World War.

At the time, this job was given to computors. No, that is not a typo. Before the Second World War, computors were people, and during the war, due to it being a low-status job and the desire to free up men for combat duty, it was usually done by women. In this case, hundreds of them.

Enter physicist Dr. John W. Mauchly, who was already entertaining the idea of building an electronic computer to analyze the weather that could handle these calculations automatically at high speed. In June 1942 an agreement was signed with the US Army for "Project PX" to build what would become ENIAC at the Moore School, with Mauchy and young electronics engineer J. Presper Eckert, Jr. in charge of the design.

What was built over the next three years was a monster of a machine. It consisted of 42 panels that were 9 ft (2.7 m) high and 1.1 ft (33 cm) thick made out of black-painted sheet steel with ducts at the top to allow air to circulate and cool the tubes and a large extractor fan system in the ceiling. In addition, the computer had its own dedicated power line.

Inside were over 18,800 vacuum tubes – an unheard of number at that time. Worse, they were intended to act in a digital system where they were either on or off instead of as analog devices as they were designed. Engineers believed that having so many tubes would result in a failure rate so high that the machine might not be able to complete a single computation before breaking down.

As it was, the failure rate in the beginning was twice a day. As more reliable tubes became available, this dropped to once every two days. For this reason, the construction was modular, so a unit could be pulled and replaced rather than the faulty part being tracked down.

If the number of tubes wasn't impressive enough, there were also 70,000 resistors, 10,000 capacitors, 1,500 relays, 6,000 manual switches, and five million soldered joints.

ENIAC had no way to store programs, so it had to literally be rewired for every new task. This was done by a crew of female operators who would pull and re-plug cables and set switches for each new set of calculations.

In fact, led by Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Fran Bilas and Ruth Lichterman, they were the world's first computer programmers – a job for which there wasn't even a name. Without even a manual, they had to learn schematics and work with block diagrams to write the programs and instructions on how to reconfigure the machine on paper. As it was, it took days to program ENIAC and weeks to debug.

ENIAC never did any actual war work. It wasn't even run until three months after the surrender of Japan, but it was already doing work on the first hydrogen bomb when the Las Alamos National Laboratory learned of its existence.

Then, on February 15, 1946, ENIAC was unveiled to the press. As part of this, the Pathé newsreel cameras were invited to film the tubes flashing as the computer solved a missile trajectory in 20 seconds – 10 seconds before the shell would have landed.

Unfortunately, the cameras couldn't see the lights, so neon bulbs were installed on the tubes and then covered with ping pong balls cut in half with numerals painted on them. As ENIAC worked, the results flew across the panels in a display so dramatic that for decades the public associated computers with control panels covered with flashing lights.

It also introduced the idea of the computer as a mysterious, all-powerful giant electronic brain that would be smarter than humans by teatime next Wednesday when ENIAC was basically a spreadsheet app. In other words, ENIAC didn't just introduce the computer age, but the myth of HAL 9000 and Skynet.

Oddly, ENIAC's creators didn't share the public's opinion. By the time they'd frozen the design, Mauchly and Eckert had come up with a much more advanced computer called EDVAC. While ENIAC was improved and continued to work until it was shut down in 1955, Mauchly and Eckert started the first commercial electronic computer company, the Eckert–Mauchly Computer Corporation (EMCC), which would go on to build the famous Univac computer that processed the US census data in 1950 and predicted the winner of the 1952 US presidential election.

Today, ENIAC has long been broken up, but its surviving panels are on display at the University of Pennsylvania, the Smithsonian, the Science Museum in London, and other locations.