Britain's hush hush Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) intelligence and security organization has released new images never before made public of Colossus, the world's first digital electronic computer, to mark its 80th anniversary.

If there's one thing that Britain's intelligence agencies are notorious for, it's their emphasis on secrecy. From For Your Eyes Only to destroy-all-evidence-and-pretend-it-never-happened, keeping things under wraps for up to a century is a matter of routine.

One of the most dramatic cases of this is Colossus, which is arguably the first digital electronic computer ever made and formed a pivotal role in defeating Germany during the Second World War. Despite being so historically important, its existence was completely unknown outside of the inner circles of GCHQ until the 1980s and never officially acknowledged until about 20 years ago.

When these revelations were made, it not only shed new light on the war, but forced a rewriting of the history of computers and computer sciences. Many pioneering machines were knocked a step or two down the ladder and it turned out that Colossus was so advanced for its time that some aspects of it remain classified to this day.

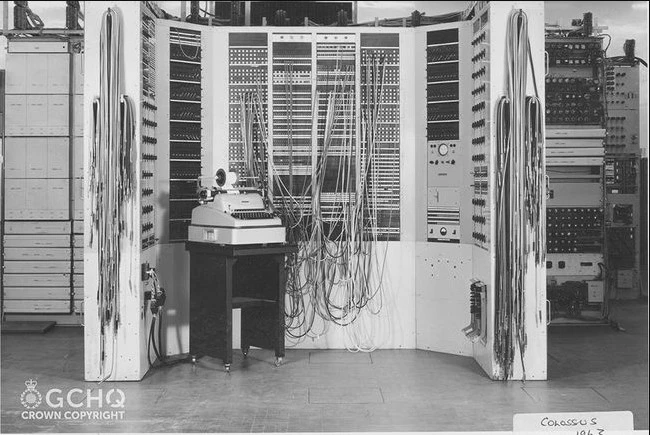

Standing two meters (6 ft) high and containing 2,500 radio valves, with its peripherals it was so big it took up a large room. Ten Colossus machines were eventually built, with the first going online on February 5, 1944 and the second on June 1 of that year, possibly in anticipation of the D-Day invasion.

The purpose of the machines was to break the state-of-the-art codes used by the Nazi high command, telling the Allies in almost real time what the German General Staff were saying to each other. They even confirmed that Hitler had been fooled by an Allied deception and believed the D-Day forces were landing at Pas De Calais, not the beaches of Normandy.

The newly released images include new pictures of Colossus as well as of the Wrens (Women's Royal Naval Service) who attended it. Security was so tight that the women had no idea what the machine was doing, nor did the technicians tasked with building and repairing it.

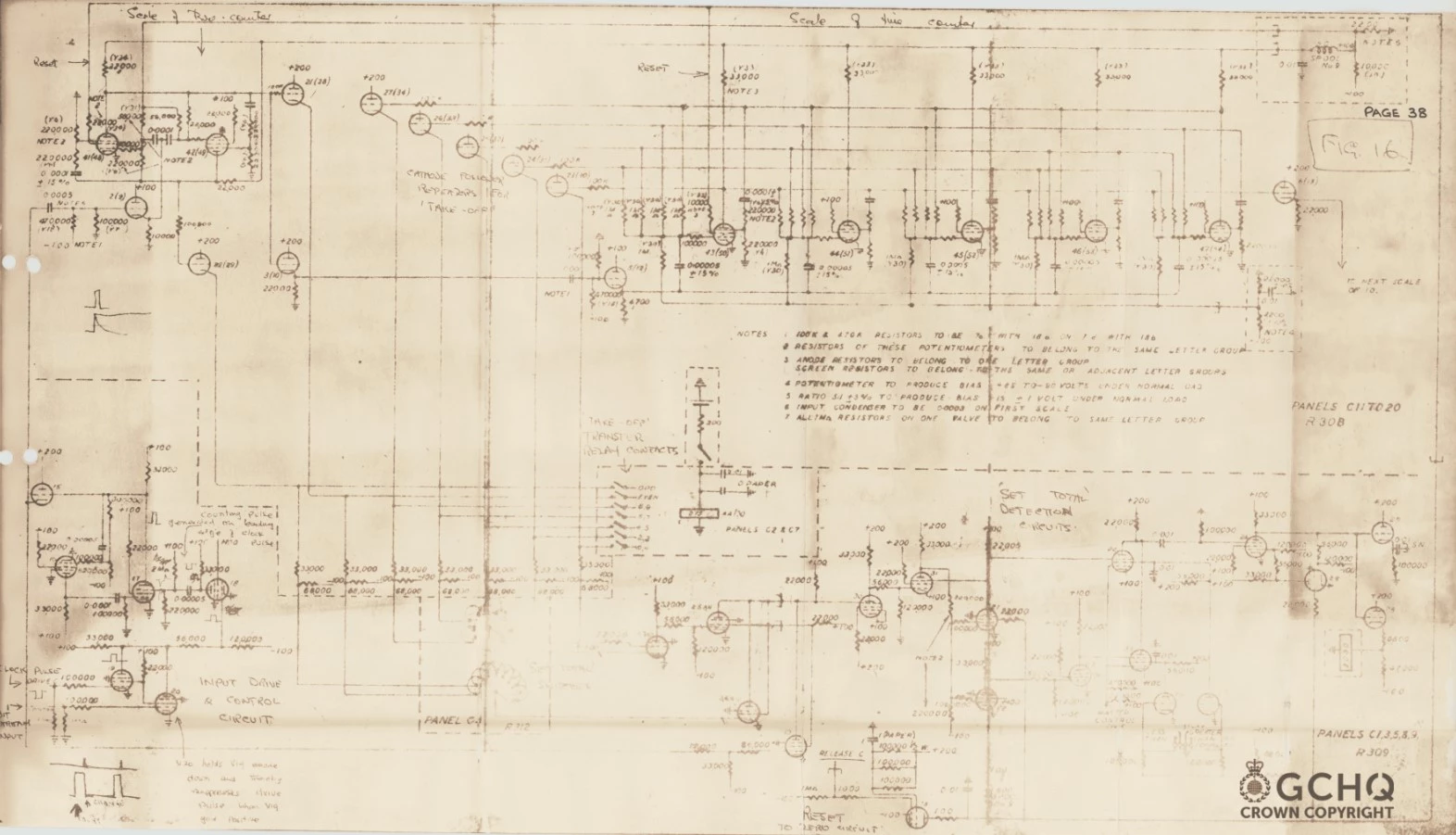

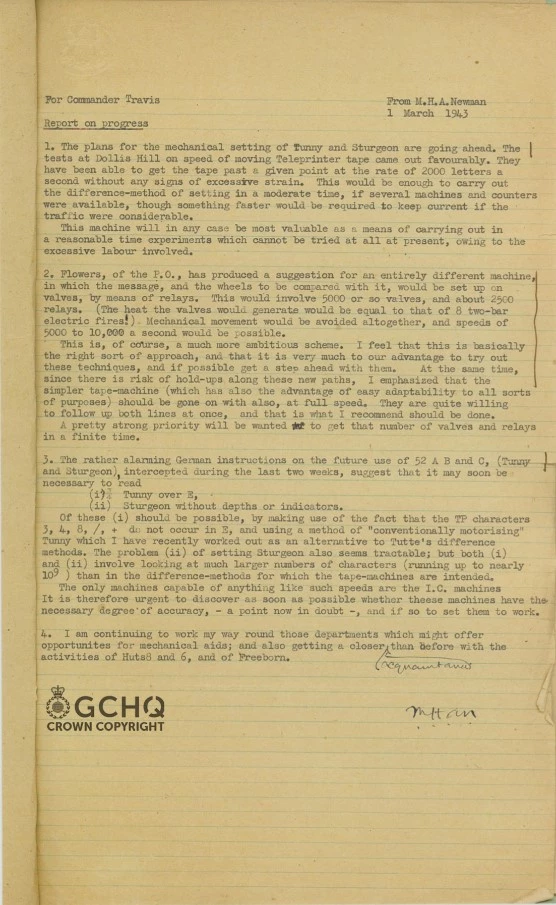

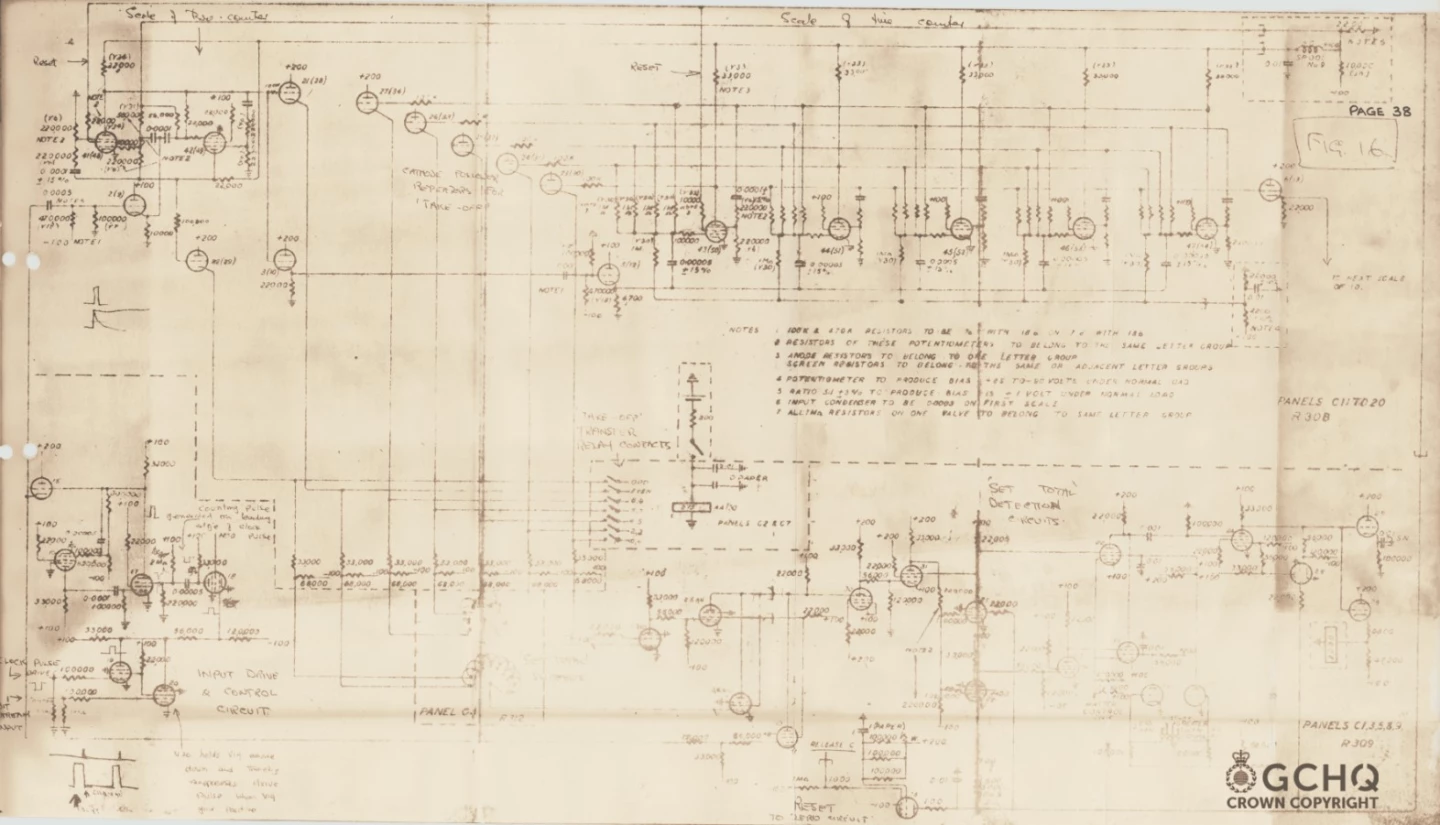

Another image is of a letter that mentions Thomas "Tommy" Flowers, who was a General Post Office engineer who was the architect of Colossus, which he designed to be built with off the shelf telephone exchange components. In addition, if you're ambitious and have a soldering iron, there's even a page of Colossus schematics.

"Colossus was perhaps the most important of the wartime code breaking machines because it enabled the Allies to read strategic messages passing between the main German headquarters across Europe," said Andrew Herbert OBE FREng, Chairman of Trustees at the National Museum of Computing. "This is one of the many reasons we’re so proud to have a fully working reconstruction of a Colossus code breaking machine on display at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park.

"From a technical perspective, Colossus was an important precursor of the modern electronic digital computer, and many of those who used Colossus at Bletchley Park went on to become important pioneers and leaders of British computing in the decades following the war, often leading the world in their work. We are proud to join with GCHQ in celebrating this significant date in the Colossus legacy."

Source: GCHQ