We humans are obsessed with storytelling. We tell stories to people we meet and people we love. We can't get enough of the stories that drive movies, video games, television, and books. We communicate with stories, and now we're training our computers to do the same. By writing sets of rules and instructions of varying complexity, artificial intelligence experts can enable computers to write stories both real and fictional. Some of these algorithms, as you'll see shortly, produce articles or reports with the sort of flair you'd think only a human could provide, which has fascinating implications for the future of publishing.

"Our CEO likes to say that the old model is to write one story and hope that a million people read it and our model is that we can write a million stories and we know that almost everybody will read it because each of those stories can be targeted for an audience as small as one," says Automated Insights media and public relations manager James Kotecki.

Automated Insights produces stories from data, using algorithms. The more data that its Wordsmith platform can work from, the better. Wordsmith writes corporate earnings reports for the likes of Associated Press (AP), which has seen its quarterly output of such articles increase tenfold – from 300 to 3,000 – since adopting the automatic prose generator.

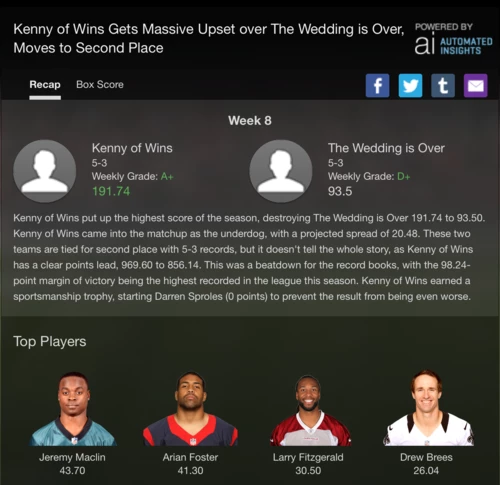

It also churns out complete drafts of marketing reports according to provided style and formatting guidelines. And it writes personalized, snark-laden reports for Yahoo fantasy football teams, every week for every team, based on data from players' specific teams and leagues. You can watch a video below that shows what Wordsmith does.

Wordsmith's work can read like it was written by a robot, but it's largely a matter of style. Its AP news articles are dry and efficient in exactly the same way as human-authored AP stories, while its fantasy football automated draft reports and match recaps smack of the snark-laden personality you'd expect from an overworked sports journalist – even including jokes and slang.

Rival service Narrative Science is finding similar success as it branches out from the automated news reporting that put its Quill software in the limelight and increasingly shifts focus to enterprise clients on Wall Street and in the US intelligence community.

These robot writers aren't going to put anyone out of a job. Quite the contrary, their overlords argue. They can do the grunt work, the stuff that nobody likes to do but is necessary for the job, like writing cookie-cutter earnings reports or summarizing the week's happenings in sport. Their strength is that they take mountains of raw structured data, which humans find difficult to parse and understand, and translate it all into clear, flowing sentences and paragraphs that get across the core ideas or statistical highlights in a simple story. Writing follows rules that can be broken down and taught to a computer, and matters of style are often as simple as tweaking a few variables.

They can even write the formulaic data-driven elements of deeper stories, ready for a journalist or marketer to come in and add quotes, further analysis, relevant history, and anything else that needs a human touch. In that sense, Kotecki points out, "Wordsmith is like a junior reporter or reporting assistant."

From reports to full-length books

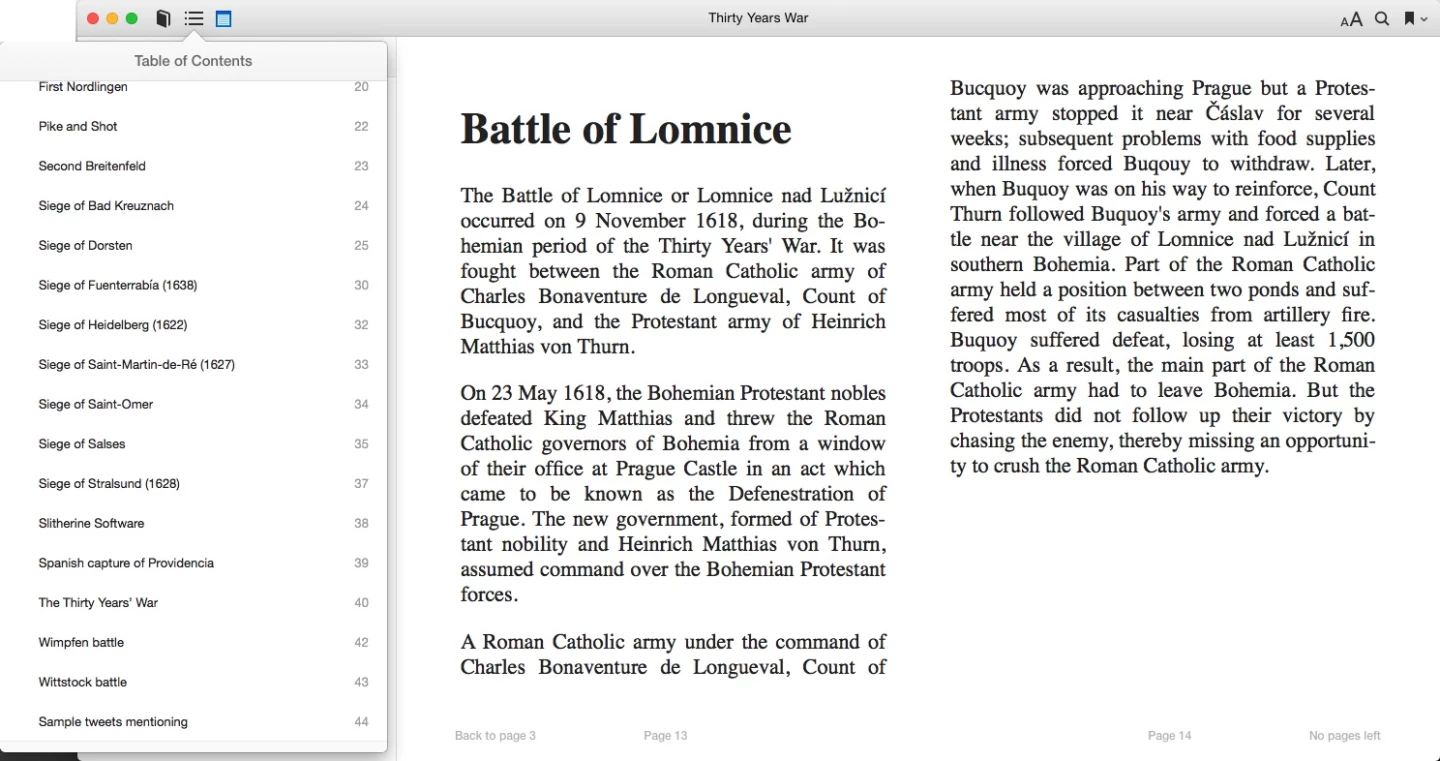

Replicating the work of short-form writers is one thing, but what of books? Well, it depends on what you're looking for. Nimble Books CEO and publishing entrepreneur Fred Zimmerman made headlines in 2012 for his algorithms that produce complete books on a given topic from simple queries. His PageKicker service has been largely silent since that initial burst of attention, but this year Zimmerman plans to return from the shadows with an improved version of the same idea.

PageKicker's algorithms start with simple strategies like "find all content whose title includes the keyword," Zimmerman tells Gizmag. They scour online sources such as Wikipedia together with publisher-submitted documents and combine and arrange the results in alphabetical order. Soon they will arrange documents more organically with clustering methods that help move the system a little closer to author rather than curator.

The software will continue to evolve and become more robust. Zimmerman noted in a Skyrim, for example, will send you to a random part of the map to kill a random animal and bring back to a random non-playable character," explains Riedl. "That's a story. It's not a very compelling story…[but] we can generate those things all day long."

Video games are effectively micro worlds, which makes it easy to define complete possibility spaces and to know everything about everything within these spaces. That, in turn, opens the door to algorithmically-generated stories. AI systems excel when they have robust definitions of everything. But the real world is huge, messy, and dynamic ... always in flux, never understandable.

"We'll just never have a complete chunk of knowledge about how the real world works, and that's when our computer systems tend to fail," explains Riedl.

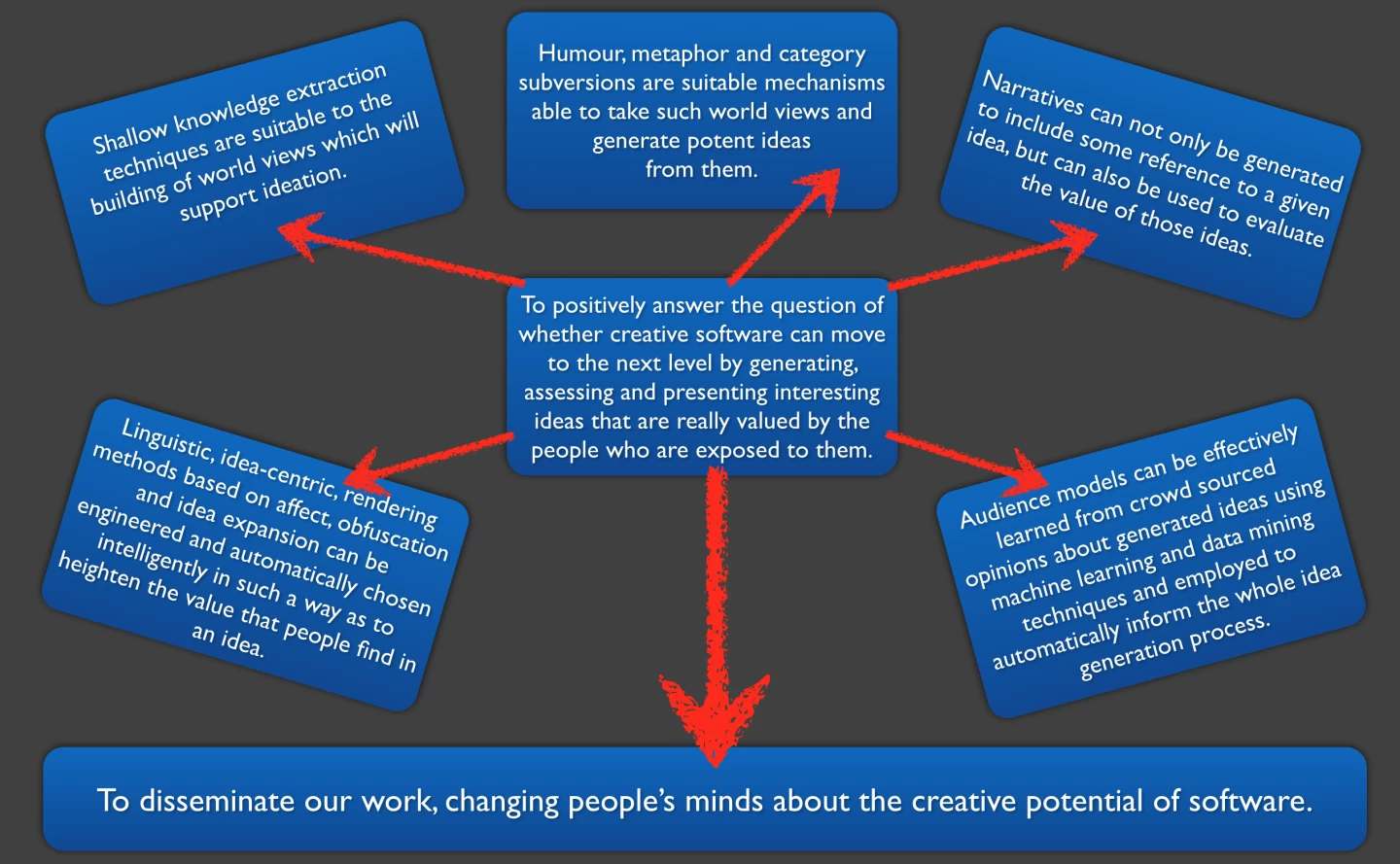

Researchers are making progress on real or open-world storytelling, with another notable effort being the What-if Machine (WHIM) research project in Europe, which is teaching computers to understand humor and metaphor as well as to generate its own narrative ideas. But what these systems can produce remains a far cry short of human storytellers. Riedl readily admits that the stories his systems generate are unimpressive in human terms, with little or no deeper meaning and plots that only outdo the most generic of Hollywood action flicks.

Composer and algorithmic music researcher David Cope, a semi-retired professor from the University of California Santa Cruz and one of our interviewees for the creative AI in music feature, has also spent years trying to crack the AI writing nut, with limited success.

The problem, Cope believes, is that stories are meant to communicate ideas, whereas art and music composition are more abstract. "When you compose a piece of music, you don't expect the person listening to it to get the exact same feeling you had when you wrote it, because it's abstract" Cope argues. "It's a bunch of black lines and circles that's being interpreted by people playing instruments for which the sounds that they make have no precise meaning."

Writing, on the other hand, communicates meaning, and that meaning is often hidden within the text – read "between the lines" of words and sentences that say one thing but mean another.

"Computers fundamentally don't understand what they're doing, no matter how beautiful the outcome may be in terms of its artistic or creative potential," says Cope. "They are running through a set of instructions to achieve a planned goal of some sort, so there's no understanding there."

A computer would struggle to come up with something like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in other words, because it doesn't know how to marry plot with meaning (and it struggles to even achieve a decent plot).

The best Cope has managed is to produce three paragraph snippets that read like they've just been pulled out of a larger story. Beyond that, he says, even a decent short story generator that goes beyond assembling prefabricated elements is far beyond what anyone has been able to produce yet.

"Basically, [with AI] you can tell really long stories about really well-known worlds – like game worlds – or you can tell short stories about really messy real-life worlds," explains Riedl. "It's telling long interesting stories about messy open worlds that is the thing we just don't know how to do yet."

Computers can now package stories that exist in data form, of which there is increasingly an embarrassment of riches, or generate simple plots from artificially-small worlds of possibility with little difficulty, but they are at a loss to provide critiques or full-formed narrative inventions of their own.

Getting to that point will take a number of steps. The next part of the challenge looks likely to be teaching computers aesthetic evaluation, which we'll be digging into as part of the final entry in this series. But first we have a couple of detours to make. Next week we turn our gaze on algorithmic art.