You've probably heard music composed by a computer algorithm, though you may not realize it. Artificial intelligence researchers have made huge gains in computational – or algorithmic – creativity over the past decade or two, and in music especially these advances are now filtering through to the real world. AI programs have produced albums in multiple genres. They've scored films and advertisements. And they've also generated mood music in games and smartphone apps. But what does computer-authored music sound like? Why do it? And how is it changing music creation? Join us, in this first entry in a series of features on creative AI, as we find out.

Semi-retired University of California Santa Cruz professor David Cope has been exploring the intersection of algorithms and creativity for over half a century, first on paper and then with computer. "It seemed even in my early teenage years perfectly logical to do creative things with algorithms rather than spend all the time writing out each note or paint this or write out this short story or develop this timeline word by word by word," he tells Gizmag.

Cope came to specialize in what he terms algorithmic composition (although, as you'll see later in this article series, that's far from all he's proficient at). He writes sets of instructions that enable computers to automatically generate complete orchestral compositions of any length in a matter of minutes using a kind of formal grammar and lexicon that he's spent decades refining.

His experiments in musical intelligence began in 1981 as the result of a composer's block in his more traditional music composition efforts, and he has since written around a dozen books and numerous journal articles on the subject. His algorithms have produced classical music ranging from single-instrument arrangements all the way up to full symphonies by modeling the styles of great composers like Bach and Mozart, and they have at times fooled people into believing that the works were written by human composers. You can listen to one of Cope's experiments below.

For Cope, one of the core benefits of AI composition is that it allows composers to experiment far more efficiently. Composers who lived prior to the advent of the personal computer, he says, had certain practicalities that limited them, namely that it might take months of work to turn an idea into a composition. If a piece is not in the composer's usual style, the risk that this composition may be terrible increases, because it will not be built on the techniques that they've used before and know will generally work. "With algorithms we can experiment in those ways to produce that piece in 15 minutes and we can know immediately whether it's going to work or not," Cope explains.

Algorithms that produce creative work have a significant benefit, then, in terms of time, energy, and money, as they reduce the wasted effort on failed ideas.

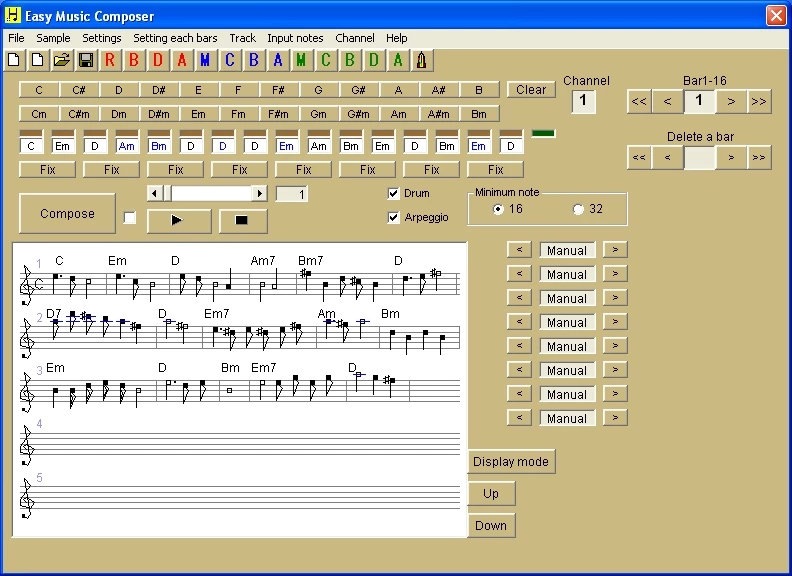

Tools such as Liquid Notes, Quartet Generator, Easy Music Composer, and Maestro Genesis are liberating to open-minded composers. They generate the musical equivalent of sentences and paragraphs with consummate ease, their benefit being that they do the hard part of translating an abstract idea or intention into notes, melodies, and harmonies.

Those with coding talent have it even better: Algorithms that a programmer can write in minutes could test any hypotheses a composer might have about a particular musical technique and produce virtual instrument sounds in dozens or hundreds of variations that give them a strong idea of how it works in practice. And Cope argues that all of this makes possible "an arena of creativity that could not have been imagined by someone even 50 years ago."

The compositions that computers create don't necessarily need any editing or polishing from humans. Some, such as those found in the album 0music, are fit to stand alone. 0music was composed by Melomics109, which is one of two music-focused AIs created by researchers at the University of Malaga. The other, which was introduced in 2010, three years before Melomics109, is Iamus. Both use a strategy modeled on biology to learn and evolve ever-better and more complex mechanisms for composing music. They began with very simple compositions and are now moving towards professional-caliber pieces.

"Before Iamus, most of the attempts to create music were oriented to mimic previous composers, by providing the computer with a set of scores/MIDI files," says lead researcher and Melomics founder Francisco Javier Vico. "Iamus was new in that it developed its own original style, creating its work from scratch, not mimicking any author."

It came as quite a shock, Vico notes. Iamus was alternately hailed as the 21st century's answer to Mozart and the producer of superficial, unmemorable, dry material devoid of soul. For many, though, it was seen as a sign that computers are rapidly catching up to humans in their capacity to write music. (You can decide for yourself by watching the Malaga Philharmonic Orchestra performing Iamus' Adsum.)

There's no reason to fear this progress, those in the field say. AI-composed music will not put professional composers, songwriters, or musicians out of business. Cope states the situation simply. "We have composers that are human and we have composers that are not human," he explains, noting that there's a human element in the non-human composers – the data being crunched to make the composition possible is chosen by humans if not created by them, and, deep learning aside, algorithms are written by humans.

Cope finds fears of computational creativity frustrating, as they belie humanity's arrogance. "We could do amazing things if we'd just give up a little bit of our ego and attempt to not pit us against our own creations – our own computers – but embrace the two of us together and in one way or another continue to grow," he says.

Vico makes a similar point. He compares the situation to the democratization of photography that has occurred in the last 15-20 years with the rise of digital cameras, easy-to-use editing software, and sharing over the Internet. "Computer-composers and browsing/editing tools can make a musicians out of anyone with a good ear and sensibility," he says.

Perhaps more exciting, though, is the potential of computer-generated, algorithmically-composed music to work in real time. Impromptu (see the video demonstration below) and various other audio plugins and tools help VJs and other performers to "live code" their performances, while OMax learns a musician's style and effectively improvises an accompaniment, always adapting to what's happening in the sound.

In the world of video games, real-time computer-generated music is a boon because its adaptability suits the unpredictable nature of play. Many games dynamically re-sequence their soundtracks or adjust the tempo and add or remove instrument layers as players come across enemies or move into different parts of the story or environment. A small few – including, most notably, Spore from SimCity and The Sims developer Maxis – use algorithmic music techniques to orchestrate players' adventures.

The composer Daniel Brown went a step further with this idea in 2012 with the Mezzo AI, which composes soundtracks in real time in a neo-Romantic style based on what characters in the game are doing and experiencing. You can see an example of what it produces below.

Other software applications can benefit from this sort of approach, too. There are apps emerging such as Melomics' @life that can compose personalized mood music on the fly. They learn from your behavior, react to your location, or respond to your physiological state.

"We have tested Melomics apps in pain perception with astonishing results," Vico says. He explains that music tuned to a particular situation can reduce pain, or the probability of feeling pain, by distracting patients. And apps are currently being tested that use computer-generated music to help with sleep disorders and anxiety.

"I would not try to sleep with Beethoven's 5th symphony (even if I love it), but a piece that captures your attention and slows down as you fall asleep – that works," Vico says. "We'll see completely new areas of music when sentient devices (like smartphones) control music delivery."

Tune in next week for the second entry in the series, as we turn our gaze to AI-created video games and AI-assisted video game development.