Researchers have developed a battery-free sensor that reacts to sound waves, such as particular spoken words, producing enough vibrational energy to power an electronic device. The novel sensor would not only reduce battery waste but could also power medical devices like cochlear implants or monitor buildings for faults.

We depend on batteries to power many of the items we use daily, everything from smartphones and toys to remote controls and flashlights. Consequently, 15 billion batteries are discarded each year worldwide, many of them ending up in landfill.

For certain devices, throwing away batteries may soon be a thing of the past thanks to researchers at ETH Zurich who’ve developed a sensor that requires nothing to power it except sound.

“The sensor works purely mechanically and doesn’t require an external energy source,” said Johan Robertsson, one of the study’s co-authors. It simply utilizes the vibrational energy contained in sound waves.”

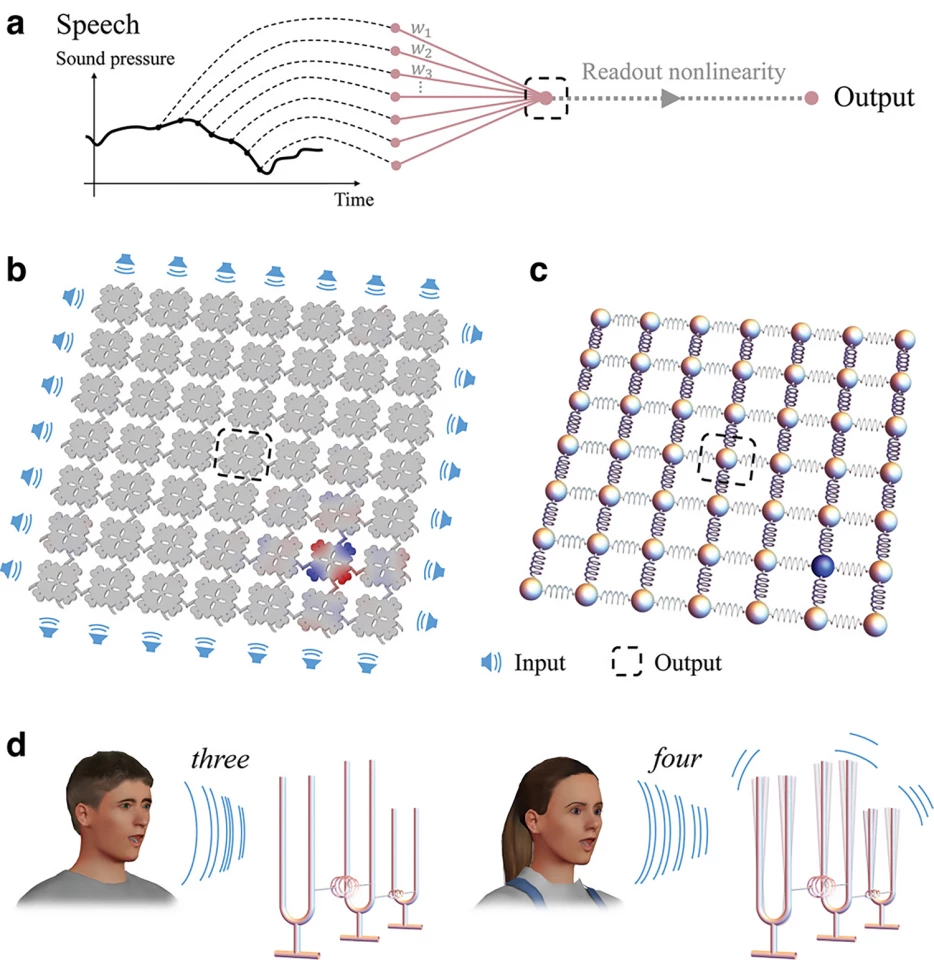

But only certain sound waves. The sensor developed by the researchers has passive speech recognition and is activated whenever a certain word is spoken or a particular tone or noise is generated. The sound waves emitted – and not others – cause the sensor to vibrate enough that it generates a tiny electrical pulse that switches on an electronic device. The prototype sensor could distinguish between the spoken words “three” and “four”. Because “four” produces more sound energy than “three,” it causes the sensor to vibrate, switching on a device or triggering a subsequent process, whereas speaking the word “three” had no effect.

The sensor is a metamaterial, which is any material engineered to have a property rarely seen in nature.

“Our sensor consists purely of silicon and contains neither toxic heavy metals nor any rare earths, as conventional electronic sensors do,” said Marc Serra-Garcia, a co-corresponding author.

But, the sensor acquires its speech recognition properties from its structure rather than what it’s made from. Using computer modeling and algorithms, the researchers designed their sensor’s structure using a lattice of identical silicon plates (resonators) connected by tiny bars that act like springs. The springs are what determine whether a particular sound sets the sensor in motion.

The researchers see many potential applications for their battery-free, sound-powered sensor. It could be used to monitor earthquakes and buildings, registering a particular sound that comes from a building’s foundation cracking, for example. Or it could detect the hiss caused by escaping gas and trigger an alarm.

They say the sensor could also have medical applications, such as for people with cochlear implants for deafness or hearing loss. Currently, each implant requires two or three batteries, depending on the type of sound processor used. While it varies based on the type of activities a person engages in, disposable batteries will last between 30 and 60 hours, requiring frequent replacements.

Or the novel sensor could be used to continuously measure eye pressure.

“There isn’t enough space in the eye for a sensor with a battery,” Serra-Garcia said. “There’s a great deal of interest in zero-energy sensors in industry, too.”

The researchers aim to release a solid prototype sensor by 2027. Newer iterations should be able to distinguish between up to 12 different words, including standard commands such as “on”, “off”, “up”, and “down”. And, compared to the palm-sized prototype, the researchers plan for the newer versions to be about the size of a thumbnail or smaller.

“If we haven’t managed to attract anyone’s interest by then, we might found our own start-up,” said Serra-Garcia.

The study was published in the journal Advanced Functional Materials.

Source: ETH Zürich