The ultimate contribution that direct air capture might make in helping us address climate change remains to be seen, but there's no shortage of startups, governments and research groups driving the technology forward. Chief among them is Swiss outfit Climeworks, which has today broken ground on its second direct air capture (DAC) plant in Iceland, and one that marks significant progress in its ambitions of removing gigatons of CO2 from the atmosphere each year by 2050.

Climeworks has operated at the cutting edge of direct air capture technology for some time, switching on the world's first "negative emission" power plant in 2017. This came about through a collaboration with carbon storage company CarbFix, which in 2016 made a major breakthrough in this area by demonstrating how CO2 can be mineralized in less than two years, rather than the hundreds or even thousands that it traditionally takes.

That pilot plant was capable of safely stowing 12.5 tons of CO2 every three months, and paved the way for Climeworks' first proper direct air capture plant, which began operation in Iceland last year. Orca, as the plant is called, is capable of absorbing 4,000 tons of CO2 each year and features a modular design consisting of stackable units, which will be key to the company's plans of scaling up its operations.

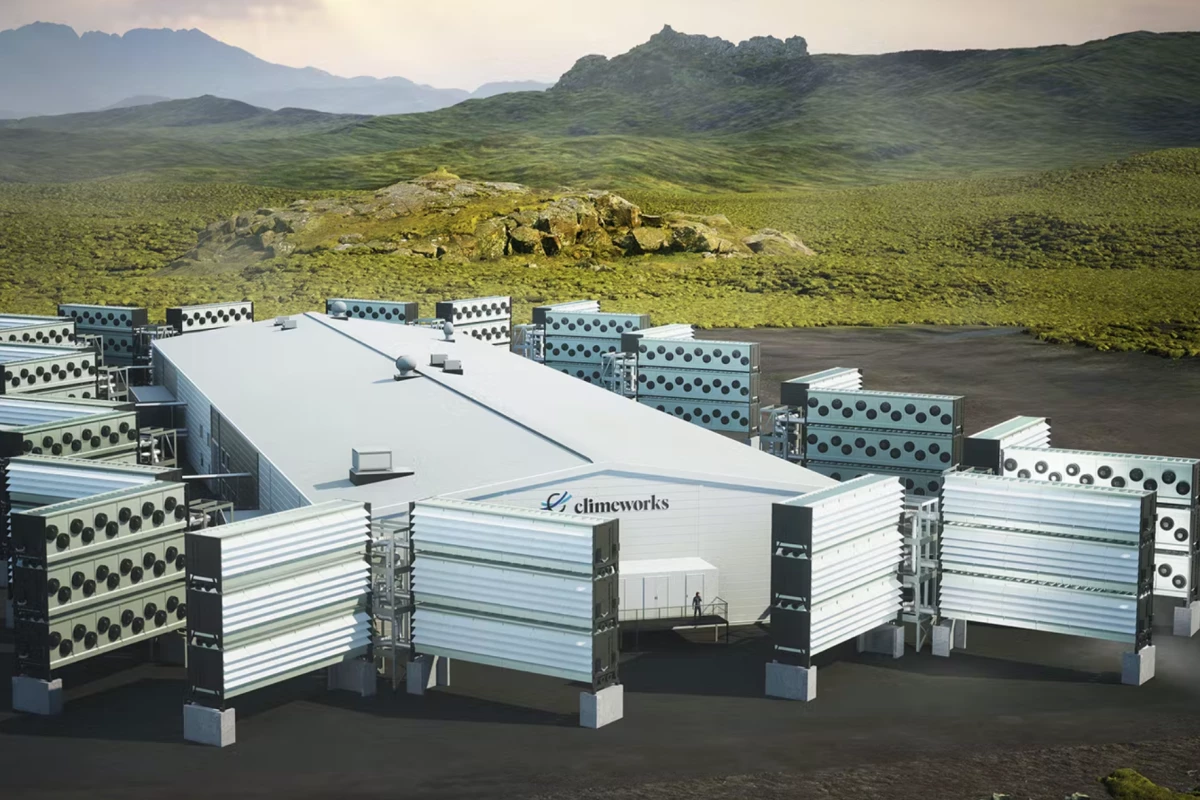

Climeworks has now broken ground on its second commercial direct air capture plant, which will also employ a modular architecture and is designed to soak up 36,000 tons of CO2 each year. Construction is expected to take 18 to 24 months, with CarbFix to store the captured carbon once operations begin. As with Orca, renewable energy will be used to run the direct air capture and storage systems.

"Today is a very important day for Climeworks and for the industry as construction begins on our newest, large-scale direct air capture and storage plant," said Jan Wurzbacher, co-founder and co-CEO of Climeworks. "With Mammoth, we can leverage our ability to quickly multiply our modular technology and significantly scale our operations. We are building the foundation for a climate relevant gigaton-scale capacity, and we are starting deployment now to remain on track for this."

Now seems like a good time to note that humankind belches out more than 30 billion tons of carbon dioxide each year, so countering this sizable addition to atmospheric CO2 would take a lot of Mammoths and a whole lot more Orcas. But Climeworks is under no illusions as to the task at hand, and sees its first plants as early but important stepping stones on a very long journey.

The US government has recently announced billions in new funding for direct air capture research, while startups from Australia to London are joining the effort by leveraging everything from solar power to carbon-gobbling algae. For its part, Climeworks is aiming to scale up to megaton-scale removal by the end of this decade, and then gigaton-scale by 2050.

“Based on most successful scale-up curves, reaching gigaton by 2050 means delivering at multi-megaton scale by 2030," said Christoph Gebald, co-founder and co-CEO of Climeworks. "Nobody has ever built what we are building in DAC, and we are both humble and realistic that the most certain way to be successful is to run the technology in the real world as fast as possible. Our fast deployment cycles will enable us to have the most robust operations at multi-megaton scale.”

Source: Climeworks