Old Nazi warheads and US warships have been reclaimed by a new army of diverse marine life, as scientists uncover how nature has made use of the munitions and fleets that ended up dumped in waterways during the two world conflicts.

In two new studies, scientists from Germany's Senckenberg am Meer Marine Research Department and Duke University in the US have, for the first time, uncovered two remarkable sites of nature reclaiming what we've left to waste – first, at a World War II munitions dumpsite in the Baltic Sea, and secondly, on the "Ghost Fleet" in Mallows Bay, Maryland, where World War I ships were sunk in the 1920s.

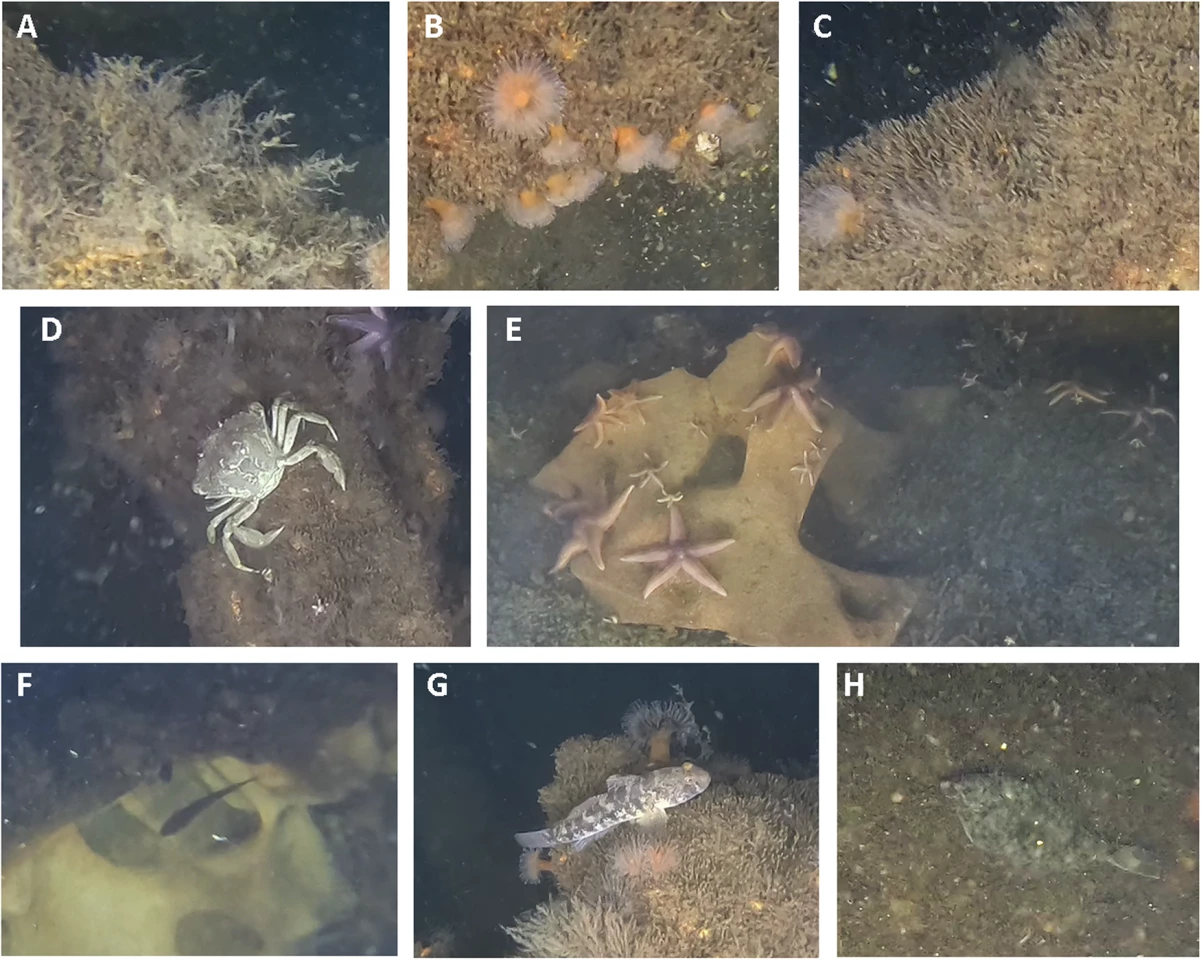

In the Baltic Sea's Lübeck Bay, researchers used a submersible to explore a newly discovered site of discarded WWII weaponry and equipment, uncovering a far richer array of wildlife inhabiting the munitions than they expected to see. The dumpsite was found to be home to warheads from V-1 flying bombs, the cruise missile used by Nazi Germany in late World War II. And they found that there was more life living on the warheads – an average of around 43,000 organisms per square meter – than in the sediment around them (8,200 organisms per square meter).

What's more surprising is that the marine life appeared to have adapted to potential toxins. The concentrations of explosive compounds (TNT and RDX) varied, from 30 nanograms to 2.7 milligrams per liter – but even at the high end, animal life was abundant. The findings reveal that some organisms can tolerate high levels of toxic compounds if the payoff is a reliable, hard surface to call home.

While the 1972 London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution put an end to the legal dumping of unused explosive munitions in the sea, these relics now provide a rich area of study for marine biologists, offering a real-world look at how animals adapt to habitat disturbances.

The researchers hypothesized that the reason there are more organisms living on the warheads than around them is because living on a solid hard surface is more advantageous than more transient substrates – and, in doing so, the organisms had become more tolerant to toxins seeping from the weapons. They also found that there were more organisms on the casings than the explosive material, suggesting that they may have tried to mitigate their exposure to the chemicals.

"Overall, the epifaunal community on the dumped munition in the study area reaches a high density, with the elevated metal structures providing a suitable habitat for benthic organisms," the researchers noted. "Although adding new hard substrates to the marine ecosystems can be questionable due to altering the surrounding habitat and even providing a possible refuge for non-native species, in the particular case of the German Baltic Sea, new hard substrata can be a conservation tool and lead to conditions closer to initial natural conditions."

In the second paper, researchers produced a highly detailed photographic map of the 147 shipwrecks in the “Ghost Fleet” of Mallows Bay, on the Potomac River, Maryland. These World War I ships were deliberately burnt and sunk in the late 1920s, and have also become rich habitats for both marine and seabird life including ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) and Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus).

The authors combined high-resolution images (an average of 3.5 centimeters per pixel) of the fleet, which had been captured by aerial drones in 2016, and present a complete work intended for future archeological, ecological and cultural research.

Study one and two were published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Sources: Duke University and Senckenberg am Meer via Scimex