The Arctic is one place that’s been hit particularly hard by climate change. Now a new study has shown that the Arctic is beginning to transition into an entirely new climate state, leaving its predominantly frozen state behind.

While the Arctic has been characteristically cold for thousands of years, there are of course natural fluctuations within a certain range. But now, scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) have found that these fluctuations are moving out of the expected range, towards a “new Arctic” climate.

"The rate of change is remarkable," says Laura Landrum, lead author of the study. "It's a period of such rapid change that observations of past weather patterns no longer show what you can expect next year. The Arctic is already entering a completely different climate than just a few decades ago."

With sea ice levels hitting record lows and temperatures hitting record highs in recent years, the team wanted to investigate whether the Arctic was fundamentally a different climate than it was just a few decades ago. To do so, they used large amounts of observational data of Arctic climate conditions to statistically define the boundaries of the “old Arctic” range, and used hundreds of computer simulations to project conditions forward.

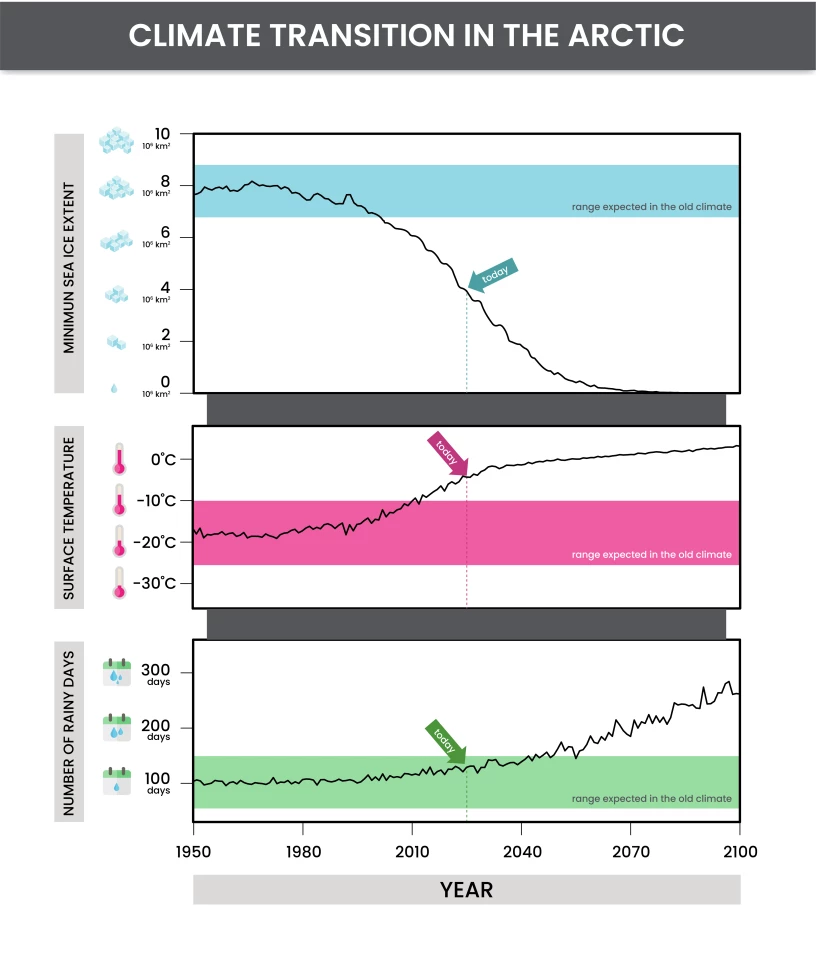

The three major factors they took into account were late summer sea ice extent (when it’s at its lowest point annually), fall and winter air temperatures, and when precipitation switches from mostly snow to mostly rain.

The team applied statistical techniques to define when the usual changes in each of these three figures exceeded natural variation. Basically, if a given 10-year average of a number was more than two standard deviations away from its average in the 1950s, then it constituted a new climate.

By this reasoning, the team found that for sea ice extent, a new climate already emerged around the turn of the century. The average September minimum is now 31 percent lower than it was in the decade 1979 to 1988. If greenhouse gas emissions remain high, the team predicts that by the end of this century the Arctic could experience between three and 10 months a year with almost no sea ice.

The models suggest that air temperatures over the ocean will enter a new climate by 2050, with air temperatures over land following in the second half of the century. And for precipitation changes, the team found that by mid-century the rainy season will likely be between 20 and 60 days longer, and up to 90 days longer by 2100.

"The Arctic is likely to experience extremes in sea ice, temperature, and precipitation that are far outside anything that we've experienced before," says Landrum. "We need to change our definition of what Arctic climate is.”

Of course, as comprehensive as our models can be, these kinds of predictions aren't always entirely accurate. Climate is an intricate web of factors, including overlooked ones like algae blooms and new ozone layer holes, others that we underestimate, and others still that we aren't even aware of. Exactly how this all plays out is still up for debate, but with so many independent studies reaching similar conclusions, the next century is set to be a transformative one for the top of the world.

The research was published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Source: NCAR