Although wind turbines generate electricity via an eco-friendly process, the giant blades of those turbines typically end up in landfills once they wear out. That could change, however, thanks to a new bio-based resin that would allow old blades to be broken down and recycled into new ones.

While designs do vary between manufacturers, most wind turbine blades incorporate a carbon fiber "skeleton" (known as a spar cap), a balsa wood or expanded foam inner core, and a fiberglass shell. In both the carbon fiber and the fiberglass, an epoxy thermoset resin is used to bond the respective fibers together.

Unfortunately, once a blade has reached the end of its operational life – after about 20 years – separating all of those materials from one another for subsequent reuse is very difficult. This is due mainly to the fact that the resin can't easily be broken down, so the carbon and glass fibers can't be retrieved from it.

Although a number of experimental blade-recycling techniques have been put forward, some of those incorporate harsh processes that likely wouldn't be manageable on a commercial scale, while others reduce the quality of the fibers. As a result, old blades are usually just dumped, or are at best ground up and used as a filler in cement.

In an effort to address that problem, scientists from the US Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) have developed an alternative epoxy resin known as PECAN. Its name an acronym for "PolyEster Covalently Adaptable Network," the substance can be made from bio-based feedstocks such as waste glycerol or other non-food-competitive sugars.

After initial experiments on small samples, the researchers utilized PECAN in the construction of a 9-meter (29.5-ft)-long wind turbine blade that incorporated a carbon fiber spar cap, a balsa wood core, and a fiberglass shell.

Testing showed that its tensile strength was similar to that of blades made with traditional resins, as was its ability to withstand harsh weather. And importantly – unlike some other experimental blades made from eco-friendly materials – it wasn't prone to a phenomenon known as "creep," in which a blade deforms over time.

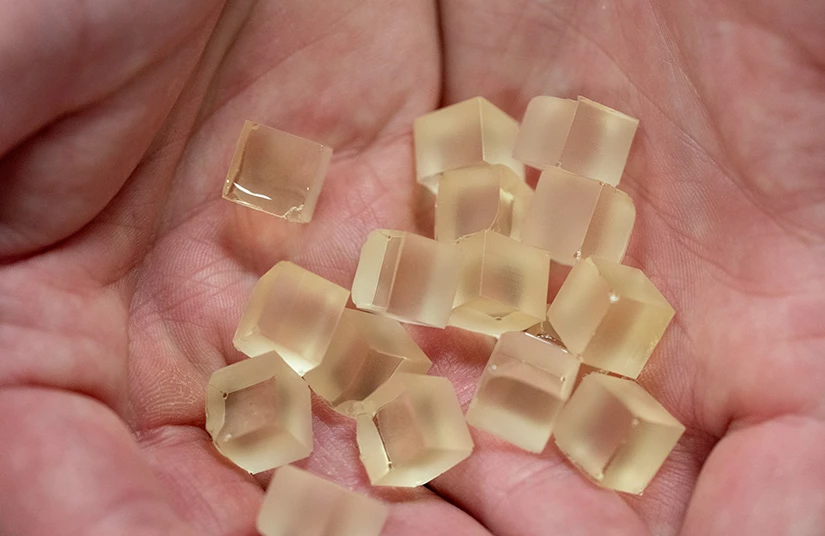

After these tests were completed, the PECAN blade was cut up into cubes which were subjected to a chemical process called methanolysis.

This process dissolved the resin in about six hours at a temperature of 225 ºC (437 ºF), allowing the pristine carbon and glass fibers to be completely recovered. The catalyst chemical that had been used to harden the resin was also recovered. And as an added bonus, a compound by the name of polyol – which formed as a byproduct of the depolymerization of the resin – was recovered for possible subsequent use in plastics such as polyurethanes.

NREL senior researcher Nic Rorrer, co-corresponding author of a paper on the study, tells us that 80% of the materials used in the blade (by mass) were ultimately recovered. The balsa wood did undergo some loss of mass, although further research may help change that.

"Just because something is bio-derivable or recyclable does not mean it's going to be worse," he says. "It really challenges this evolving notion in the field of polymer science, that you can't use recyclable materials because they will underperform."

The paper was recently published in the journal Science.

Source: NREL