The world's oceans are currently under threat not only from large pieces of plastic trash, but also from minuscule "microplastic" particles – many of which take the form of fibers that are shed by synthetic fabrics as they're being washed. A new system uses sound to help capture those fibers at their source.

First of all, scientists have already developed filters that help to remove microplastic fibers from the wastewater that drains out of washing machines. Such filters usually have to be cleaned or replaced, however, plus their pores do allow particularly small fibers to pass through.

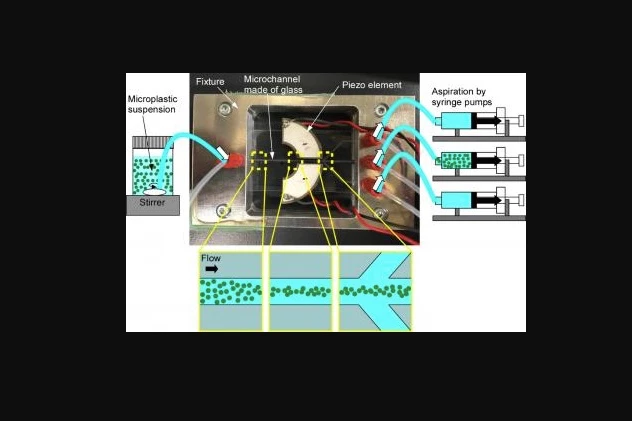

With these limitations in mind, researchers at Japan's Shinshu University have designed what's known as a bulk acoustic wave (BAW) system. It starts with a central stream of microplastic-fiber-laden wastewater, that forks into three separate channels. Just upstream of the forking point, a piezoelectric device is used to apply acoustic waves from either side of the central stream, creating a standing acoustic wave in its middle.

The fibers congregate within that wave, and are subsequently all carried down the middle channel – clean, plastic-free water goes down the two side channels. This means that the clean water could proceed into the sewer system, while the fiber-heavy water could be collected for disposal (which would likely involve evaporating the water, then collecting the fibers).

In lab tests, the BAW setup was found to capture 95 percent of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) fibers, and 99 percent of Nylon 6 fibers. Before the system can enter production, though, the fiber-separation process needs to be speeded up, as it would currently take washing machines quite a long time to drain.

A paper on the research, which is being led by Professors Hiroshi Moriwaki and Yoshitake Akiyama, was recently published in the journal Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical.

Source: Shinshu University via EurekAlert