A new study has found that exposure to second-hand smoke during pregnancy and actually smoking increase the risk of placental abruption, a complication that can be fatal to both parent and baby, to almost the same degree.

We all know about the health risks of smoking. For decades, smoking during pregnancy has been heavily discouraged due to studies linking the habit to serious effects such as low infant birth weight, preterm births, stillbirths and infant death. Not to mention the impact on the health of the pregnant person. And then there’s the issue of second-hand smoke exposure.

A new study by researchers from the Graduate School of Medicine at Tohoku University in Japan has found that smoking while pregnant, including being exposed to second-hand smoke, increases the risk of placental abruption, a serious complication that can be fatal for both parent and infant.

“Even if the mother doesn’t smoke at all, their partner may smoke at home, thinking it won’t be a problem,” said Senior Assistant Professor Hirotaka Hamada from Tohoku University Hospital, the study’s corresponding author. “Our study will hopefully raise awareness that any exposure to smoke is harmful for pregnant women.”

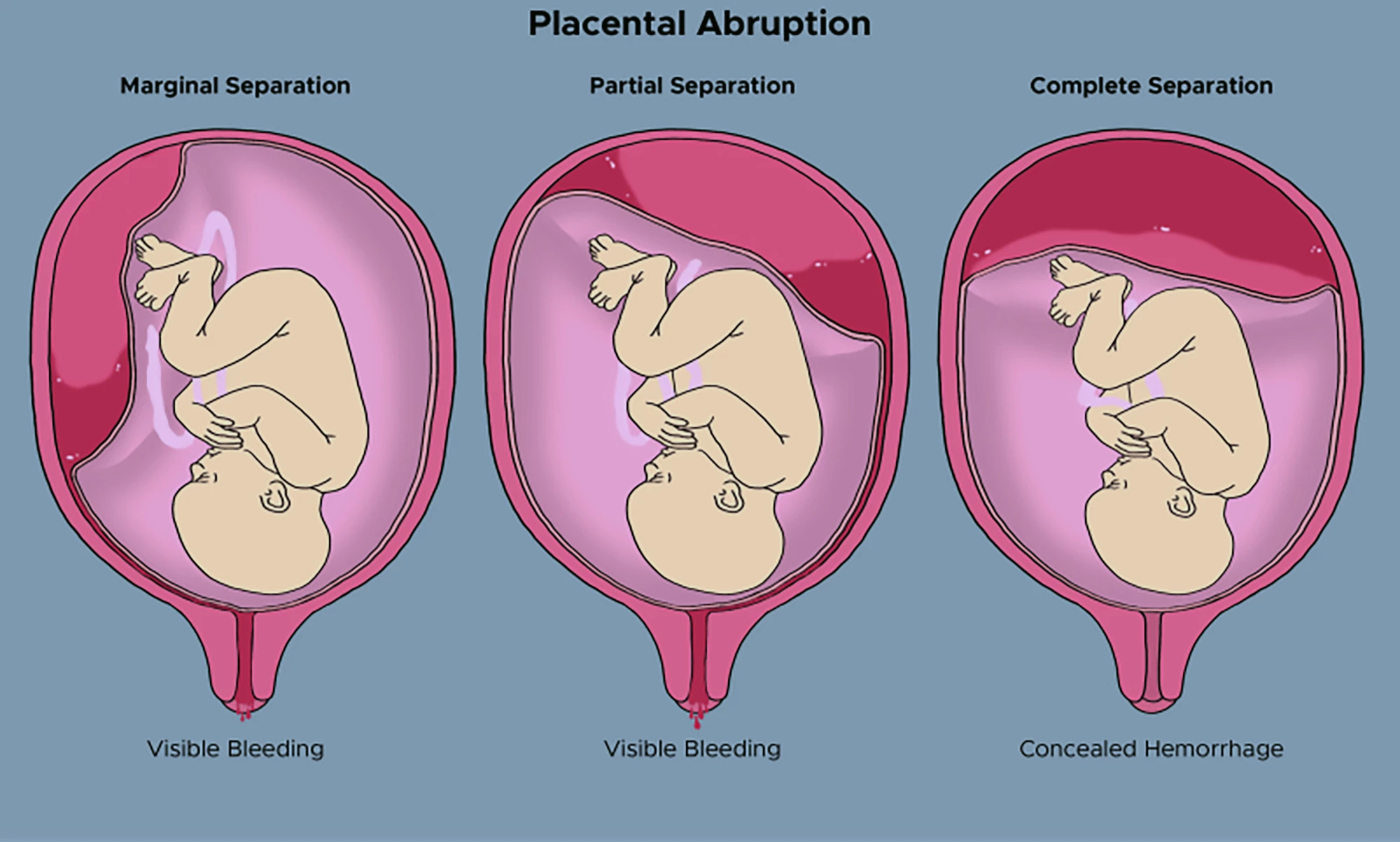

Placental abruption is as bad as it sounds. It’s where the placenta – essentially the developing baby’s lifeline – partially or completely detaches from the wall of the uterus before the baby is born. It’s potentially fatal because it cuts off the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the baby and can cause the parent to bleed heavily.

The present study used data from 81,974 pregnant women collected for the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JCES), a nationwide birth cohort study conducted in Japan to evaluate the effects of environmental factors on children’s health and development. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was categorized by the number of cigarettes smoked per day, either 10 or fewer, or 11 or more. Second-hand smoke (SHS) exposure during pregnancy was evaluated by frequency and duration. The primary outcome was the incidence of placental abruption.

The researchers found that smoking 11 or more cigarettes a day during the first and/or second trimester significantly increased the risk of placental abruption. Their adjusted risk ratio (aRR) was 2.21, meaning that smokers were 2.21 times more likely to experience placental abruption than non-smokers. After calculating the adjusted population attributable fraction (aPAF), which gives the percentage of cases that could be prevented if a risk factor was completely removed from a population, the researchers found that 1.9% of placental abruption cases could be prevented if the pregnant women in this category didn’t smoke.

What was more concerning were the findings about SHS exposure. The researchers found that pregnant women who’d never smoked but were exposed to SHS four to seven days a week for an hour or more a day had an aRR of 2.34, meaning they were 2.34 times more likely to experience placental abruption than non-smokers. The aPAF for this population was 1.89%, suggesting that SHS exposure contributes to placental abruption cases almost as much as smoking itself. The aRR was 2.21 for pregnant women who both smoked during pregnancy and were exposed to similar amounts of SHS.

“Our findings suggest that SHS exposure significantly increases the risk of placental abruption, even in pregnant women who smoke during pregnancy,” said the researchers. “This indicates the importance of not only discouraging maternal smoking but also avoiding SHS exposure during pregnancy."

The study had a few limitations. First, the data on smoking and SHS exposure was self-reported, so it was subject to underestimation and recall bias. Second, although the researchers adjusted for known confounders, factors that can cause placental abruption, such as cocaine use, abdominal trauma and uterine surgery, were not included in the dataset and, therefore, couldn’t be adjusted for.

Further study is needed to identify the specific factors that influenced pregnant people to continue smoking or be exposed to SHS, and to understand the various factors that contribute to the risk of placental abruption associated with smoking and exposure to SHS during pregnancy.

The study was published in the journal BMJ Open.

Source: Tohoku University