As useful as steel is, its main weakness may be its vulnerability to corrosion. Researchers in Korea have now developed a new alloy coating that boosts steel’s resistance to rust, by adding a simple extra step in the surface treatment.

Steel is often coated in other metals to improve its corrosion resistance, but the salty marine environment poses an extra challenge. Aluminum is a common anti-corrosion coating, but it itself tends to react with chloride ions in seawater and rust easily.

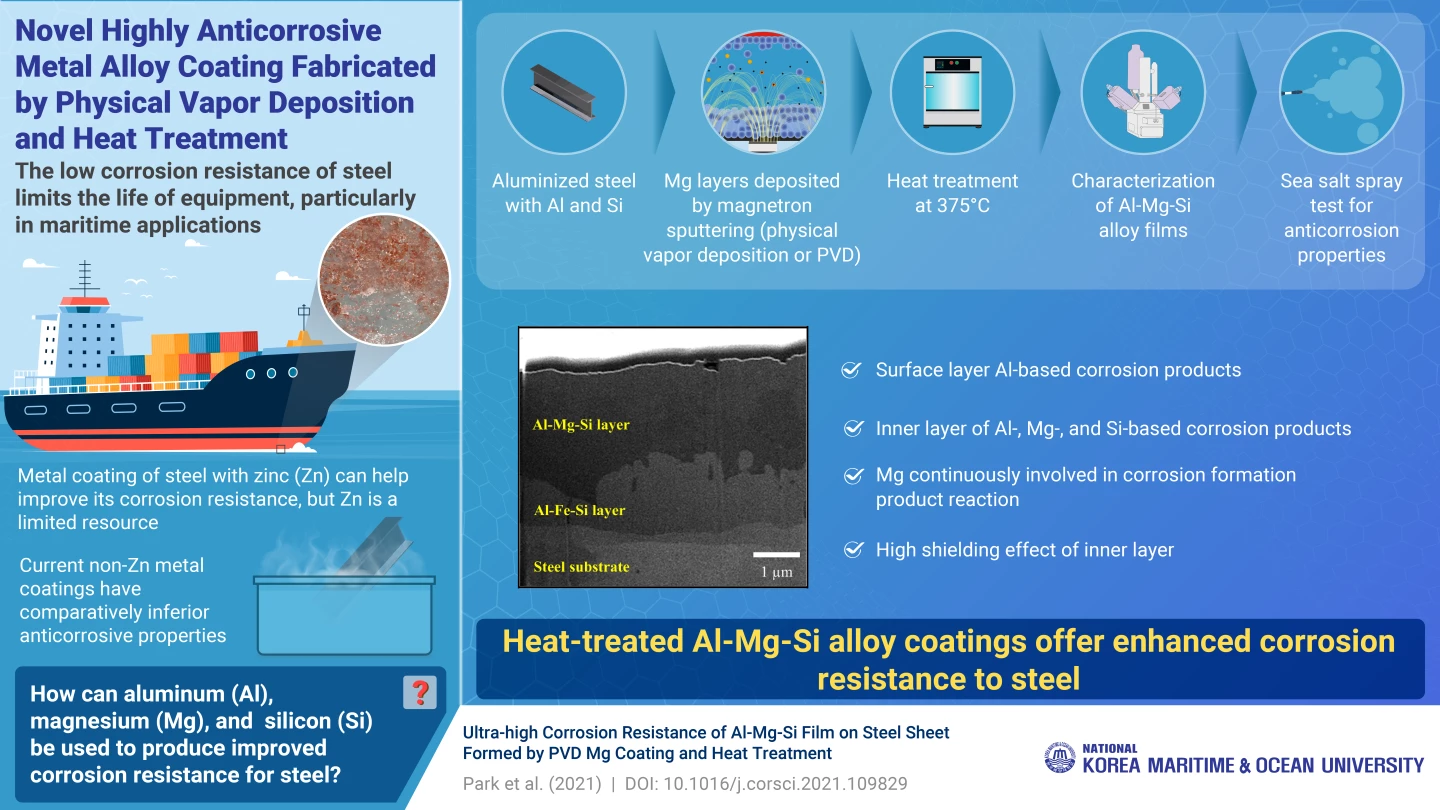

So for the new study, engineers at the Korea Maritime and Ocean University (KMOU) developed a new alloy coating made of aluminum, magnesium and silicon (Al-Mg-Si). The team started with aluminized steel, which is steel that has been hot-dipped in a bath of aluminum and silicon to coat it. The missing ingredient – magnesium – can’t be applied through this method, so the team coated the steel using physical vapor deposition. Finally, the coating was then exposed to a high temperature of 375 °C (707 °F), for different amounts of time.

The team then tested the corrosion resistance of the new coating by subjecting it to a standard salt spray test. They compared versions of the new alloy that had been heated for zero, five or 30 minutes, as well as a regular aluminized steel sheet and a galvanized steel sheet.

And sure enough, the new coating performed far better than the other materials. The aluminized and galvanized steel sheets showed significant rusting after 800 hours of salt spray exposure. The non-heat-treated new alloy fared better, but was corroding significantly by 1,600 hours. The alloy that was heat-treated for 30 minutes showed very little rust until the 2,000-hour mark, by which time it rapidly built up. But the clear standout was the alloy that had been heated for five minutes. Even when the test ended after 2,400 hours, very little corrosion had occurred.

On closer inspection, the team identified the mechanism behind the coating’s anti-corrosion properties. The corrosion products formed two layers – those near the surface were mostly aluminum-based, while those deeper down were made up of aluminum, magnesium and silicon. This inner layer created a shielding effect that protected the steel from corrosion for longer. The initial heating of the samples helped this process along by allowing the magnesium to migrate deeper into the material.

It’s important to note that salt spray tests don’t have a direct correlation to real-world corrosion rates – they are, after all, a concentrated blast designed to speed up a process that can take years or decades in a normal environment. They also can’t take into account all factors, such as wetting and drying cycles and other corrosive agents besides plain saltwater. But the results do suggest that the new alloy coating has great potential.

“Our research reveals how a highly corrosion-resistant steel can be produced using a simple change in the surface treatment protocol,” says Professor Myeong-Hoon Lee, lead author of the study, “This makes it very meaningful for conserving energy and environmental resources.”

The research was published in the journal Corrosion Science.

Source: KMOU