Bacteria are evolving to elude our drugs at an alarming rate, so much so that the UN has declared antibiotic resistance a global health emergency with the expectation that it could kill millions upon millions each year by 2050. Researchers are learning more all the time about the tricks these cunning microbes use to evade our best defences, and scientists in Australia have just confirmed another, watching on for the first time as bacteria shed their protective shells and changed their shape to escape detection by antibiotics.

Bacteria can develop drug resistance in quite a few ways. Some are able to flush the antibacterial drugs away while some divide and stop growing to evade the immune system. Others are able to deploy enzymes to break down and even eat the drugs, and others enter a state of hibernation and wait for the danger to pass.

In a new study led by scientists at the Newcastle University, a team of researchers has focused on one of bacteria’s key defenses, the cell wall.

“Imagine that the wall is like the bacteria wearing a high-vis jacket,” explains lead author, Dr Katarzyna Mickiewicz. “This gives them a regular shape, for example a rod or a sphere, making them strong and protecting them but also makes them highly visible – particularly to human immune system and antibiotics like penicillin.”

The flip side of this equation is that bacteria can also get by without their cell wall, and when they do, it is difficult for the immune system to detect them because human cells don’t have one of their own to refer to. This tell-tale sign is key to the success of common antibiotics like penicillin, which rely on this foreign and distinctive membrane as a signal to attack and leave other, unwalled cells unharmed.

On the occasion that conditions are suitable for survival, a bacterium can shed its cell wall and take on an L-shaped form. In this state, the body finds it very hard to detect the bacteria, as do antibiotics deployed to attack them. Scientists have known of the existence of these bacteria since the 1930s, but their evasive nature also makes them hard to study in any great detail.

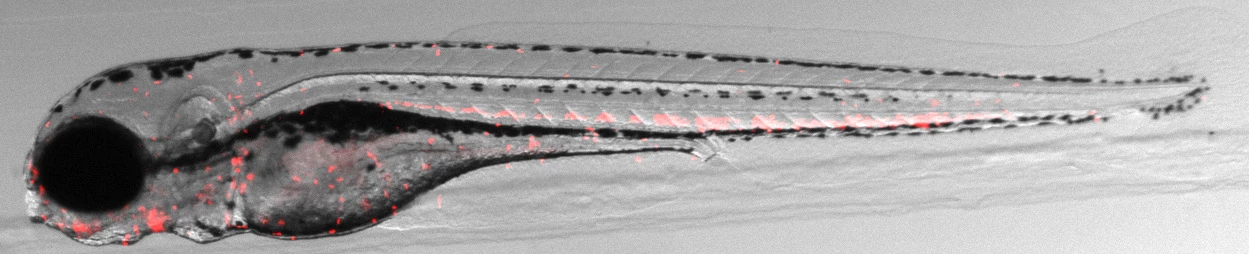

Now, using fluorescent probes that reveal bacterial DNA as markers, the Newcastle University team was able to observe them in action for the first time. The team placed bacteria from recurring urinary tract infections in a lab dish with a high sugar concentration, which is key to allowing the bacteria to survive without their walls.

The researchers added penicillin to the mix, an antibiotic that relies on targeting the cell wall to destroy the bacteria, and watched on as various species shed their walls and changed their shapes to stay hidden. This, the scientists say, is the first direct evidence of this so called L-form switching taking place.

Interestingly, the team also captured video of the L-form bacteria responding to the absence of antibiotics. Once the drugs had gone, the bacteria actually reformed the protective cell wall within around five hours. Importantly, they also observed the L-form switching taking place beyond the lab dish in a zebrafish model, watching it play out in a whole living organism.

“In a healthy patient this would probably mean that the L-form bacteria left would be destroyed by their hosts’ immune system,” says Mickiewicz. “But in a weakened or elderly patient, like in our samples, the L-form bacteria can survive. They can then re-form their cell wall and the patient is yet again faced with another infection. And this may well be one of the main reasons why we see people with recurring UTIs. For doctors this may mean considering a combination treatment – so an antibiotic that attacks the cell wall then a different type for any hidden L-form bacteria, so one that targets the RNA or DNA inside or even the surrounding membrane.”

The team has published its research in the journal Nature, and you can see L-form bacteria regain its cell walls in the video below.

Sources: The Conversation, Newcastle University