With its extremely narrow and delicate blood vessels, the brain poses a unique challenge for surgeons trying to get at its various nooks and crannies, and there are limitations to what current catheters can achieve. Scientists have developed a first-of-a-kind "steerable" catheter that takes inspiration from insects to safely navigate the brain's arteries and blood vessels, which could open up new possibilities for treating hard-to-reach aneurysms.

An aneurysm is an abnormal swelling in the wall of a blood vessel. Neurosurgeons currently tackle aneurysms in the brain by first inserting wires into an artery near the groin, which guide a catheter onward through the aorta and up into the brain. These wires feature a curved tip that is used to navigate around the many corners and junctions until the aneurysm is found.

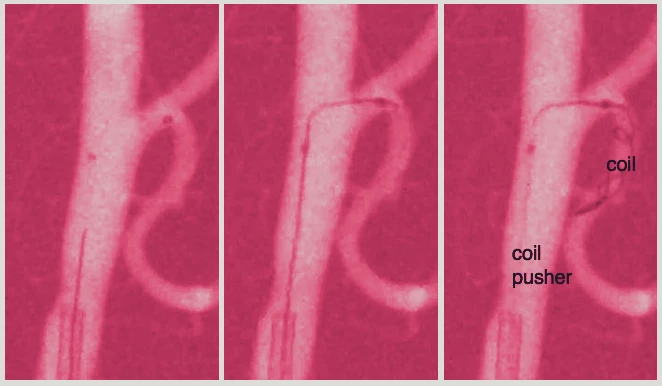

The trouble is that the guidewires then need to be removed so that the catheter can deliver platinum coils to block blood flow to the aneurysm and prevent brain bleed. But this retrieval process often dislodges the catheter and shifts its position, meaning the some types of aneurysms can be very difficult to treat.

Among those are unruptured intracranial aneurysm on the cerebral artery, blister-like lesions that are prone to rupture and affect more than 160 million people around the world. Around a quarter of these cannot be treated, because the aneurysm is simply too difficult to reach, leaving sufferers at risk of rupture, which also means a risk of death and long-term disability.

“Unfortunately, many of the most important blood vessels we need to treat are among the most tortuous and fragile in the body,” said James Friend, a professor of medical engineering at University of California (UC) San Diego and study author. “Although robotics is rising to the need in addressing many medical problems, deformable devices at the scales required for these kinds of surgeries simply do not exist.”

To create them, Friend and his colleagues looked to the animal kingdom, and specifically, the type of deformation and microscale hydraulics on show in mating beetles, insect legs and flagella. This inspired the development of what the team calls a hydraulically actuated soft robotic microcatheter, fit for the purposes of performing delicate neurosurgery.

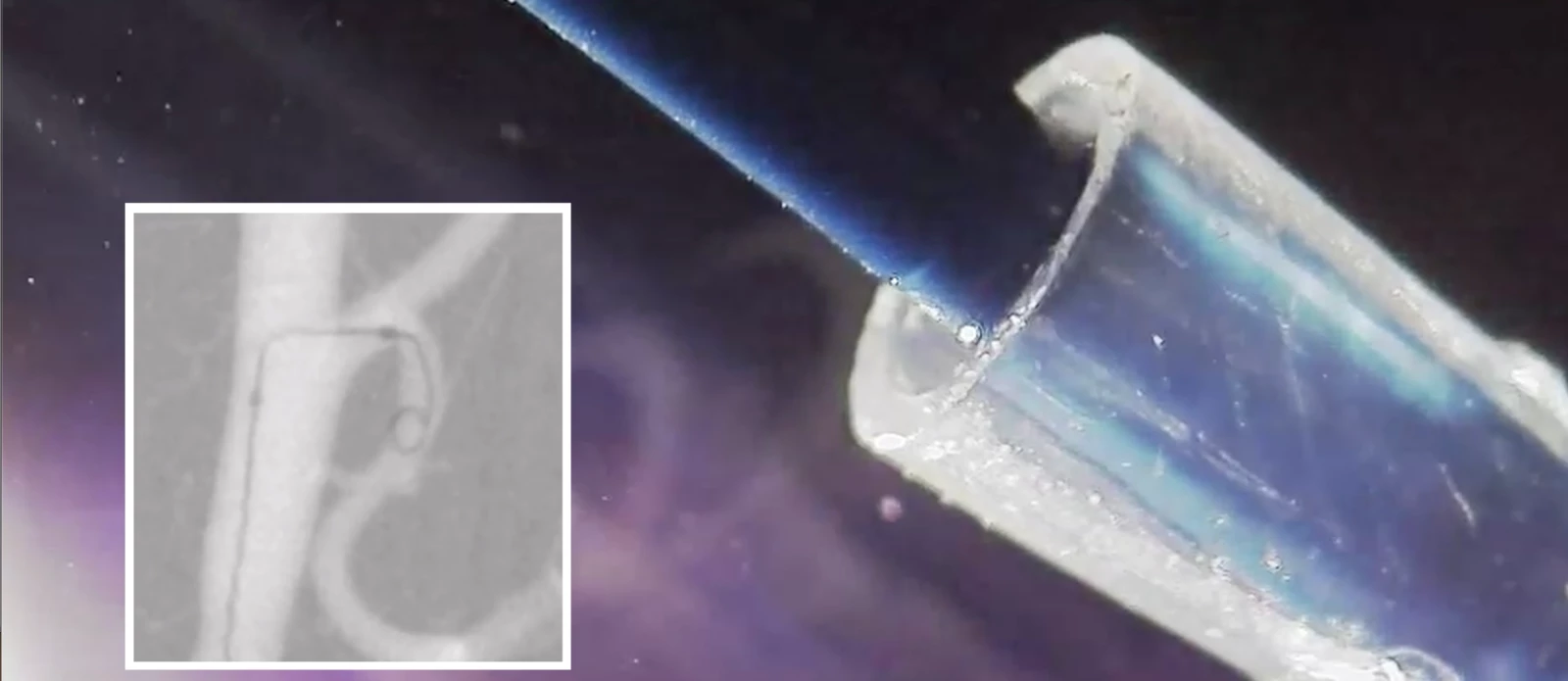

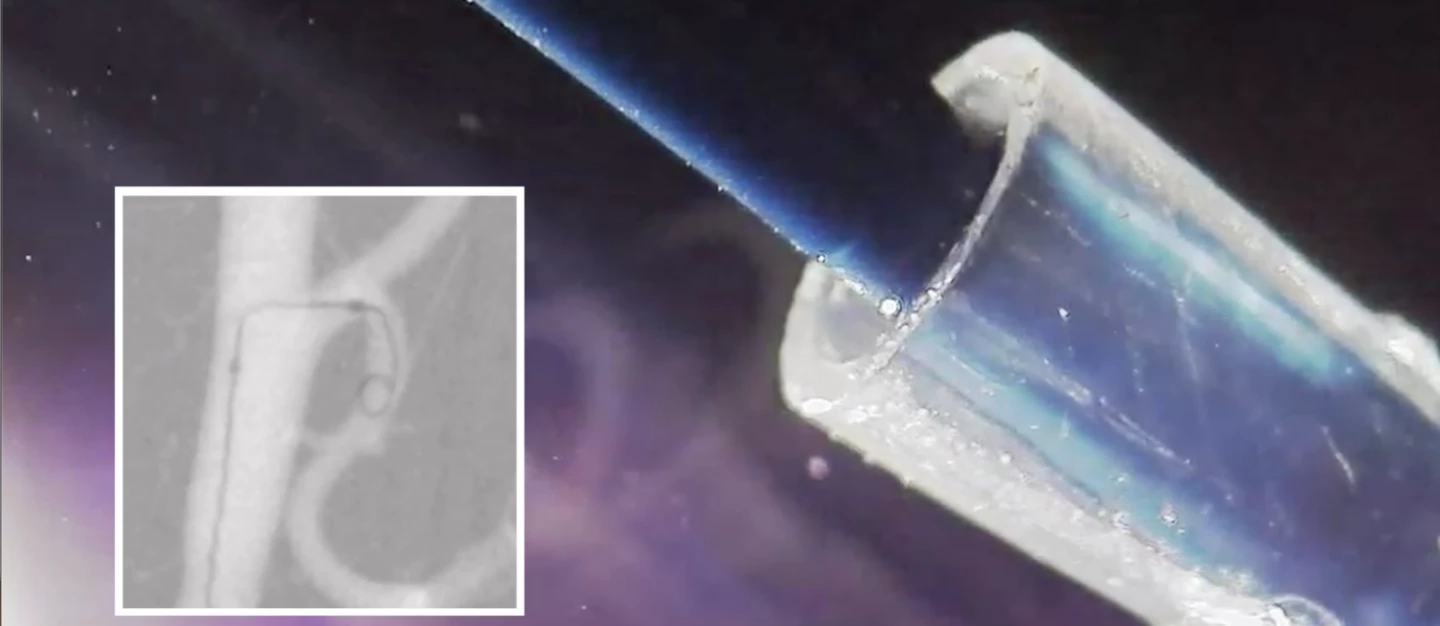

The team started by depositing concentric layers of silicone on top of one another, each with a different stiffness. This formed a silicone rubber catheter with a set of interior cavities that are pumped with harmless saline fluid via a handheld controller to add hydraulic pressure, allowing it to be steered like a "Nintendo for neurosurgeons." The technology was demonstrated in the brain artery of a pig, with the steerable tip visible on X-rays and the device proving capable of deploying the platinum coils.

“As a neurosurgeon, one of the challenges that we have is directing catheters to the delicate, deep recesses of the brain,” said Dr. Alexander Khalessi, chair of the Department of Neurological Surgery at UC San Diego Health. “Today’s results demonstrate proof of concept for a soft, easily steerable catheter that would significantly improve our ability to treat brain aneurysms and many other neurological conditions, and I look forward to advancing this innovation toward patient care.”

The researchers plan to build on these promising early results with a larger trial on animals, and eventually, humans.

The study was published in the journal Science Robotics, while you can hear from the researchers involved in the video below.

Source: UC San Diego