Researchers have built a lung in a lab that more accurately emulates the human lung than traditional models, opening the door to the fast-tracking of the discovery and development of drugs and a reduction in our reliance on animals for testing.

Lung diseases are a leading cause of death globally. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD, will become the third leading cause of death by 2030 due to worsening air quality and the after-effects of COVID-19.

COPD is an incurable condition that obstructs the small airways in the lungs, making breathing difficult, with smoking and air pollution the most common causes. Current methods of treatment are unable to reverse the damage caused to lung tissue. While newer treatments, such as stem cell-based medicines, have shown an ability to repair or prevent lung deterioration, there has been a distinct lack of new therapies approved for treating lung disease.

Traditionally, developing and testing new drugs for COPD requires animal models. The problem with using animals for testing is that some aspects of their anatomy and physiology differ from that of humans, and many animal models don’t allow for the testing of aerosol drugs.

Recently, there have been advances made concerning developing alternatives to animal models. Organs-on-a-chip, organoids – 3D structures grown from human cells that mimic real organs – and 3D-printed organs are great examples. But these have downsides, often related to their small size, limited number of cells, and lack of similarity with the complex structures and processes seen in the human lung. But now, a team led by researchers from the University of Sydney has built lungs that more accurately emulate the human lung.

“With a traditional cell culture, you put cells into a Petri dish and culture them in static conditions, which is far from what happens in a human body,” said Thanh Huyen Phan, lead author of the study. “What we are doing is creating environmental conditions similar to those which exist in the human body.”

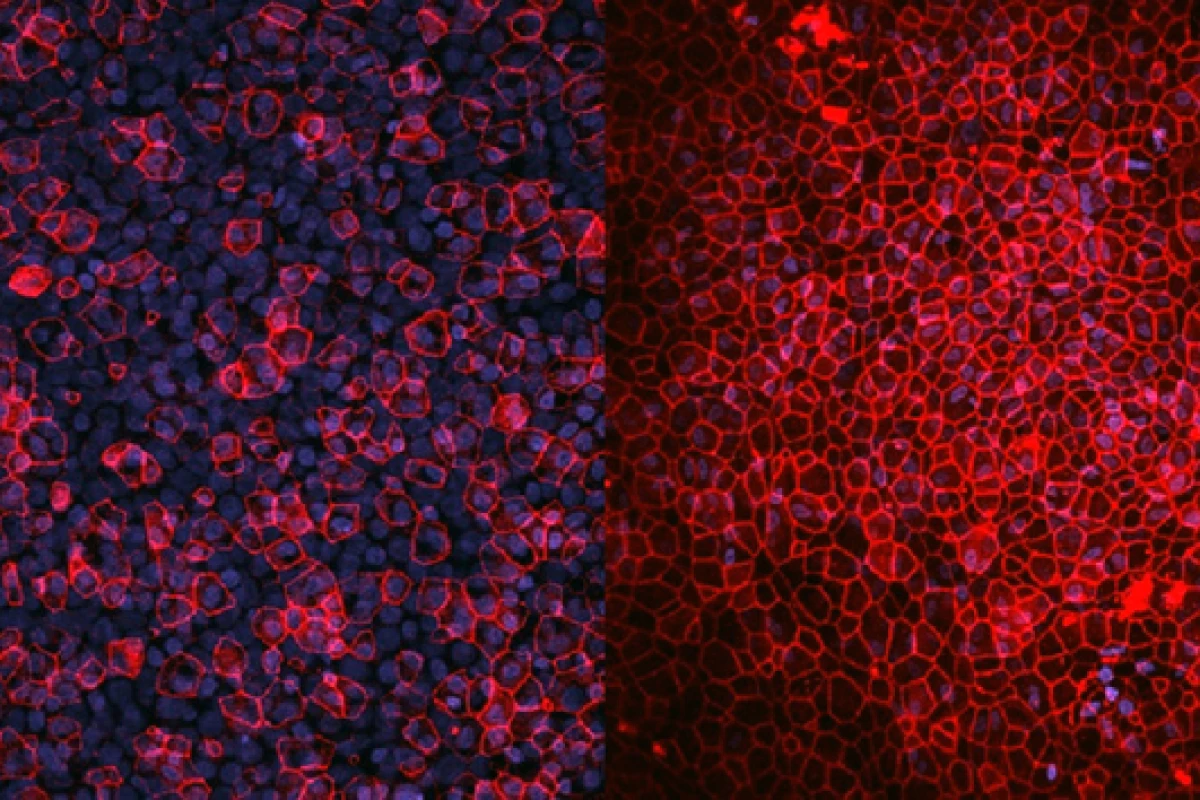

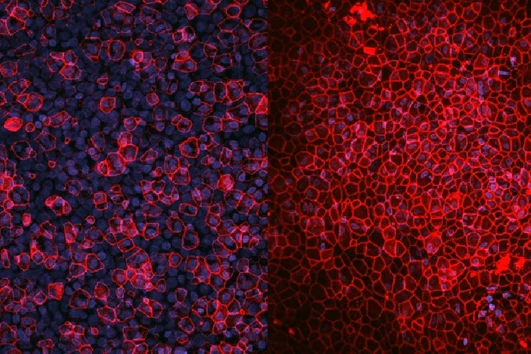

Taking cells directly from a patient, the researchers arranged them in layers, just as they appear in the body.

“We take cells directly from patients and then build them in layers as they exist inside the body,” said Wojciech Chrzanowski, the study's corresponding author. “So, first you have the epithelial cells, then you have the fibroblasts – we are literally creating a mimic organ that is very much like actual human lungs.”

The lung models are maintained under the same environmental conditions as real lungs, with air on one side and a liquid interface combined with microcirculation to mimic the body’s circulatory system on the other. The researchers created two lung models for different uses.

“We decided to build two different lung models, one of which mimics phase one clinical trials; a healthy lung to study safety of new drugs,” Chrzanowski said. “The other one mimics phase two trials; a diseased lung that, in our case, mirrors chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, enabling us to study the therapeutic effectiveness or superiority of the drugs.”

But the lung models can be used for more than just drug testing.

“These mini-lung organoid models can also be used to test toxicity,” Chrzanowski said. “For example, of silica dust or air pollutants, such as particulates generated during bushfires."

And, what’s more, they can be individualized.

"Because we can take cells directly from individual patients, we can build a patient’s own model to test the effectiveness of drugs on them," said Chrzanowski.

The researchers say that in addition to providing an alternative to animal testing, the advantages of their lab-made lungs are their reproducibility, reliability, and their ability to enable research cost-effectively on a large scale.

“They accelerate the process of discovery, they shorten the process of getting to clinics, but also substantially increase our confidence in the molecules we create before we go to clinical trials,” Chrzanowski said. “The normal timeline for the clinical translation of a drug is about 10 to 15 years, but when you use organoid models, you can shrink that time substantially.”

The study was published in the journal Biomaterials Research.

Source: University of Sydney