We’ve known for a while how a lack of sleep can negatively affect the brain. Studies have found that just one night of disturbed sleep increases Alzheimer’s disease-related amyloid-beta peptides. In addition to making someone unfocused, a lack of sleep can negatively affect the brain’s hippocampus, which is key to making memories.

In new research presented at this month’s Federation of European Neuroscience Societies (FENS) Forum in Vienna, researchers identified existing drugs that can restore memories seemingly lost because of sleep deprivation.

“By manipulating these pathways specifically in the hippocampus, we have been able to make memory processes resilient to the negative impact of sleep deprivation,” said Dr Robbert Havekes, association professor in neuroscience at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. “In our new studies, we have examined whether we could reverse amnesia even days after the initial learning event and period of sleep deprivation.”

The hippocampus works like the brain’s librarian, forming short-term memories that are consolidated into long-term ones, labeled and stored for later retrieval. Its role extends to both spatial and social memory. Spatial memory is our short- and long-term memory of places, events, and things in the world. It’s how we remember the route to the grocery store and find things after we’ve put them down. Social memory enables us to distinguish a familiar face from one we don’t know, so we can not only engage in meaningful relationships but express appropriate behavioral responses based on previous encounters.

Focusing on social memory, the researchers gave mice a choice of interacting with siblings or a mouse they’d never met before. Normally, mice prefer to interact with the unknown mouse over their siblings, and then, the next day, they will spend a similar amount of time with their siblings and the newly met mouse, who’s now considered familiar. However, the researchers found that mice who were sleep-deprived after first meeting the unknown mouse would interact with it the following day as if it was the first time, suggesting that that first encounter had been forgotten.

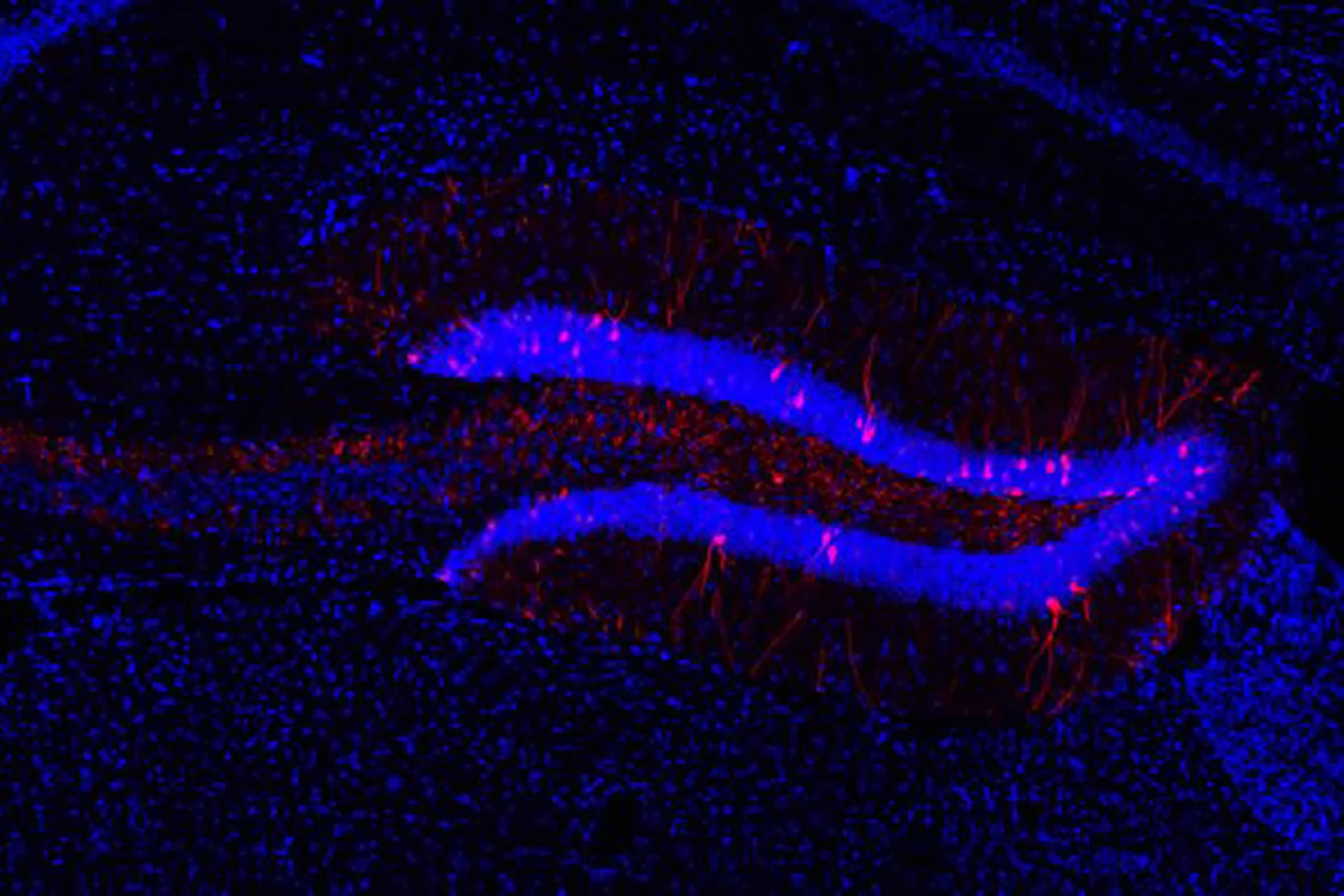

It's proposed that an experience activates a population of neurons that undergo permanent chemical and/or physical changes to become an ‘engram’ or memory trace and that an engram’s reactivation leads to memory retrieval. Here, the researchers used optogenetics, a technique that uses light to control the activity of specific neurons, to identify the neurons that formed the specific mouse-meeting memory and reactivated their engram, restoring the mice’s hidden social memory of that first meeting. They found that roflumilast (sold as Daxas, Daliresp and others), used to reduce airway irritation and swelling in severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), also produced the same social-memory-restoring effect.

The researchers conducted parallel experiments on spatial memory. Mice who were sleep-deprived couldn’t recall the locations of individual objects and so didn’t notice when an object was moved to a new location during testing. As with social memories, hidden spatial memories were restored by the drug vardenafil (Levitra and others), used to treat erectile dysfunction or impotence.

“We have been able to show that sleep deprivation leads to amnesia in the case of specific spatial and social recognition memories,” Havekes said. “This amnesia can be reversed days later after the initial learning experience and sleep deprivation episode using drugs already approved for human consumption. We now want to focus on understanding what processes are at the core of these accessible and inaccessible memories. In the long term, we hope that these fundamental studies will help pave the way for studies aimed at reversing forgetfulness by restoring access to otherwise inaccessible information in the brain.”

The research has only been presented at the FENS Forum 2024 and hasn’t been published or peer-reviewed yet.

Source: FENS via EurekAlert!