Researchers have discovered the mechanism linking the overconsumption of red meat with colorectal cancer, as well as identifying a means of interfering with the mechanism as a new treatment strategy for this kind of cancer.

Meat is a significant source of protein and fat, as well as essential vitamins and minerals like iron, zinc, and vitamins A and B. However, as is the case with many things, eating too much of it is bad for you. Despite the strong evidence associating red meat with some cancers, the underlying mechanism is less clear.

Now, researchers from the National Cancer Center Singapore (NCCS), together with scientists from Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), have identified the mechanism linking the excessive consumption of red meat to colorectal cancer.

Worldwide, colorectal cancer, which affects the large intestine or rectum, is the third most common cancer, accounting for around 10% of cancer cases. It’s also the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths. In addition to age and family history, lifestyle factors such as diet, inactivity, obesity, smoking, and excess alcohol consumption can increase the risk of this type of cancer.

Using fresh colorectal cancer samples, the researchers discovered that the iron in red meat reactivated the enzyme telomerase via an iron-sensing protein called Pirin, which drove the progression of the cancer. Now, this requires stepping back to explain the importance of telomerase and telomeres and their relation to cancer growth.

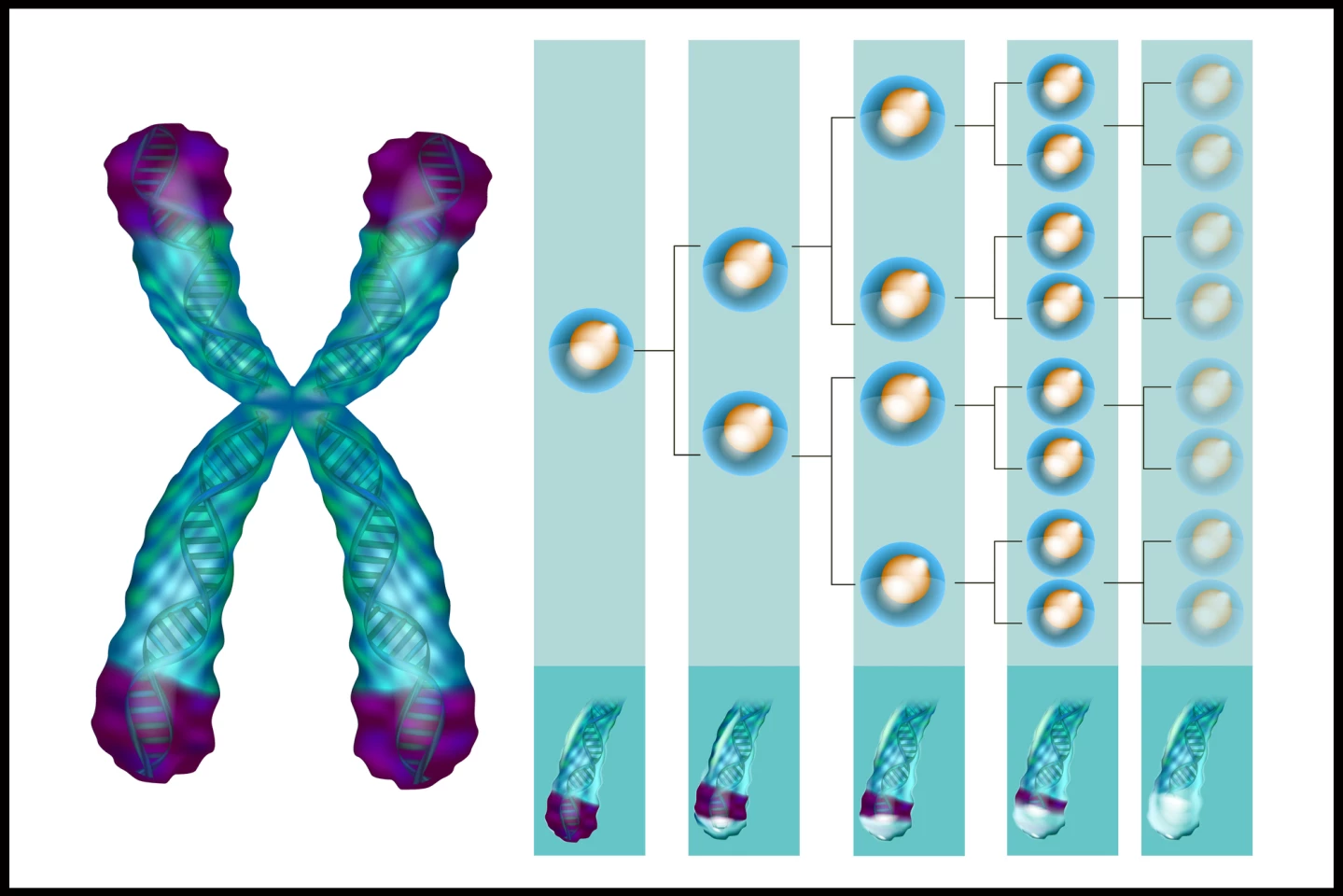

Telomeres, the little ‘caps’ found at the end of chromosomes, are made from DNA sequences and proteins and are required for cell division. With each cell division, the telomeres get shorter and shorter until they’re so short that cells can no longer divide. When cells can no longer divide, tissues age. However, the enzyme telomerase can rebuild telomeres to restore cell division.

This might sound good, but if a cell keeps dividing uncontrollably, overcoming the natural limits imposed by telomeres, it can form a cancerous tumor. Because of all the division they do, cancer cells end up with critically short telomeres, which are too short to protect the chromosomes. To avoid inevitable death, the cells make telomerase so they can continue to divide and grow, effectively becoming immortal. So, to reiterate, the researchers found that the iron in red meat reactivated telomerase in colorectal cancer cells, thus driving the progression of the cancer.

“We show how iron-(Fe3+) in collusion with genetic factors reactivates telomerase, providing a molecular mechanism for the association between iron overload and increased incidence of colorectal cancers,” the researchers said.

In addition to pinpointing this mechanism, the researchers also identified a promising new treatment approach based on it. A small molecule called SP2509 was found to block telomerase reactivation in cancer cells by targeting Pirin, preventing iron from binding with it. In lab tests on cancer cell lines, SP2509 stopped the reactivation of telomerase and reduced tumor growth; it’s a potential new treatment strategy for colorectal cancer.

“Understanding the role of iron in telomerase activation opens up new avenues for addressing colorectal cancer,” said Professor Vinay Tergaonkar, from A*STAR’s Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB) and the study’s senior author. “Our future research will focus on refining therapeutic strategies that target this mechanism, with the hope of developing more effective treatments for patients, particularly those with high iron levels. We are excited about the potential of small molecules like SP2509 to revolutionize cancer care and improve outcomes for patients globally.”

The study was published in the journal Cancer Discovery.

Source: NCCS