For some time now, it has been observed that wounds with a zig-zag pattern heal faster than those which simply form a straight line. Scientists have now determined why this is the case, and their findings could change the ways in which surgical incisions are made.

Led by Prof. K Jimmy Hsia, a team at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University started out with a micro-patterned hydrogel, the surface of which was seeded with Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Although these cells are obtained from dog kidneys, they are epithelial cells of the type that are also found in the skin.

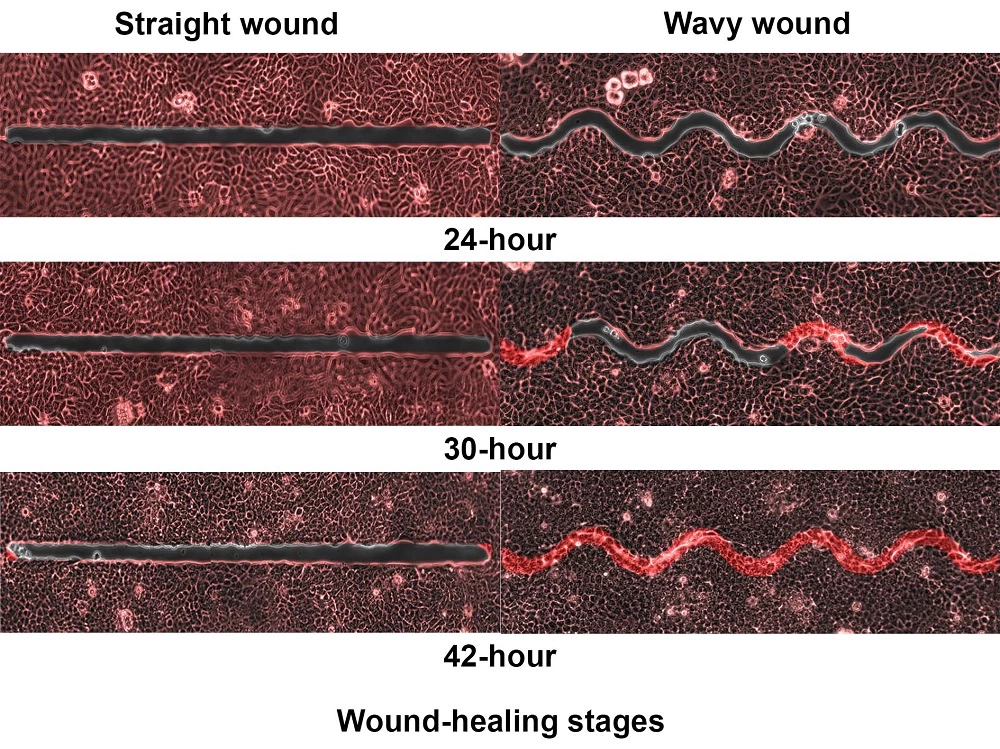

The researchers proceeded to make numerous cuts in the hydrogel, the cuts simulating wounds and the gel simulating human skin and underlying tissue. Those cuts ranged from 30 to 100 micrometers in width, and were also made in a variety of curving patterns, ranging from quite serpentine to completely straight.

Utilizing particle image velocimetry (which is an optical measurement technique for studying fluid flow), the scientists then watched for 64 hours as the cells set about bridging the gaps formed by the cuts. This process is known as re-epithelialisation, and it is the means by which external wounds naturally heal.

It was found that on the wavier wounds, the cells moved in a "swirly, vortex-like" manner. On the straight wounds, however, the cells tended to move in straight lines which ran parallel to the wound's edges. Due to this difference in cell movement patterns, the wavy wounds healed almost five times faster than the straight ones.

"The highly nonuniform and rotational motion induced by wavy wounds allowed more opportunities for cells to move around, compared to straight wounds," said doctoral student Xu Hongmei, first author of a paper on the study. "This enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps."

It is now hoped that the findings could lead to new methods of making surgical incisions which heal faster with less scarring, thus lowering the probability of complications such as infections.

The paper was recently published in the journal PNAS.

Source: Nanyang Technological University