Over the last few years, you'd struggleto have not at least heard mention of an extremely strong, electrically- and thermally-conductive, one-atom thick material called graphene. But now, researchers at theUniversity of Kentucky are looking to create a new material thatmight just boast even more impressive and useful attributes.

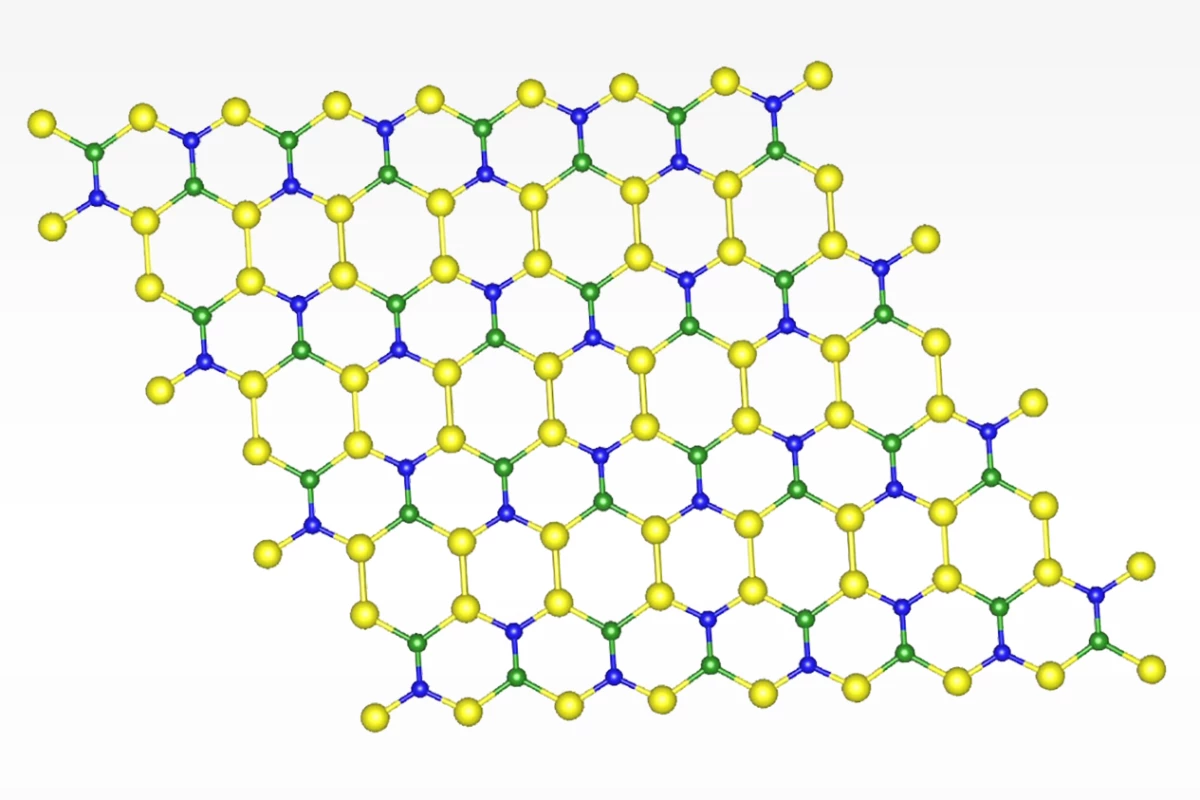

The new material is made up of amixture of silicon, nitrogen and boron, coming together to form a oneatom-thick, hexagonal structure, very similar to that of graphene. All those materials are widelyavailable, inexpensive and lightweight, and thefinished material is extremely stable – theoretically at least. Theresearchers used computer simulations to try and get the bondsbetween the different base materials to disintegrate, but found theyheld strong, even at temperatures of 1,000º C (1,832º F).

While the structure of the new materialis hexagonal – just like graphene – the different sizes of theelements used means that results in a less uniform structure, withuneven sides. However, while it might not be quite as uniform, itdoes have some significant benefits over graphene. Most notably, it can easily be turned into a semiconductorby attaching other elements on top of the silicon atoms.

The inclusion of silicon atoms in thematerial would also make it easier to integrate the material with currentsilicon-based technologies. This would avoid the need for a suddenshift in materials, instead allowing the industry to slowly move awayfrom silicon, easing the switch to smarter, more versatile materials.

At this point, the novel material only exists in a theoretical sense, with the researchers using computersat the University of Kentucky's Center for Computational Science toperform the complex calculations. The team is now working withresearchers at the University of Louisville to create the materialunder laboratory conditions.

"We are very anxious for this to bemade in the lab," said team member Madhu Menon. "The ultimate test of anytheory is experimental verification, so the sooner the better."

The researchers published their work inthe journal Physical Review B, Rapid Communication.

Source: University of Kentucky