Stories, whether fact or fiction, are at the heart of human culture. A strong narrative can resonate with your personality and experiences, and help set a framework for your future. "That book changed my life" is a cherished maxim. So can a book change your brain too? A recent study led by Emory University's Gregory Berns has demonstrated that reading a novel produces physical changes in the brain similar to those that would result from living as one or more of the characters.

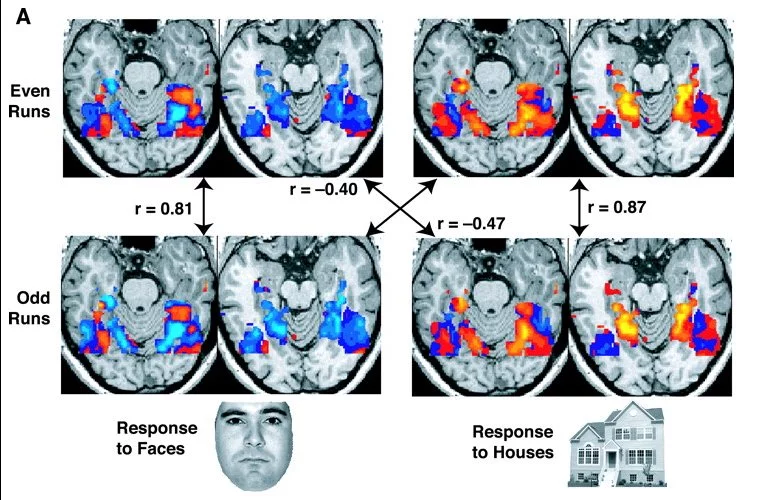

Neurobiological research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has begun to identify brain networks associated with reading stories. Most previous studies have focused on the cognitive processes involved in short stories, while subjects are actually reading them in the fMRI scanner. The Berns study, published in the journal Brain Connectivity, focused on changes in brain connectivity occurring between reading chapters of a novel, and the fading of those changes once the novel was finished.

"You live several lives while reading." William Styron.

Twenty-one undergraduate students volunteered as subjects in the experiment. For the first five days, the participants came in to the lab every morning to obtain a base-line functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measurement of their brain at rest. Then for the next nine days, they were assigned a section of a novel to read at night, returning the next morning to take a quiz covering the material in the latest section, and then taking a new fMRI scan. When the novel was finished, the participants returned to the lab each of the next five mornings for an fMRI scan to track the evolution of any changes observed during the experiment.

The novel chosen was Robert Harris' Pompeii. This historical thriller follows its protagonist through his arrival in Pompeii as the new "aquarius," or hydraulic engineer, to run the aqueduct for the area surrounding the Bay of Naples. When the flow of water suddenly stops, he suspects a blockage near its sources on Mount Vesuvius. Investigating, he becomes embroiled in a a fraudulent plan to cheat the Roman government of its water fees. Finding the proof, with the aid of a noblewoman, seems less important when the volcano decides to erupt. He rushes into Pompeii to rescue the noblewoman, and they both escape through the lower portions of the once again active aqueduct.

While prior studies suggest that connection to a story told in the first person may be more captivating (everything else being equal), the researchers chose the book due to its page-turning plot. “It depicts true events in a fictional and dramatic way,” Berns says. “It was important to us that the book had a strong narrative line ... We want to understand how stories get into your brain, and what they do to it.”

As we learn and experience, the connectome, or map of neural connections within our brain, changes. In the Emory experiment, two main classes of changes were seen. First, heightened connectivity was seen in the left temporal cortex, and area associated with understanding language. Remember that the students were not reading while the fMRI scans were being taken, which shows us that the brain remained "at alert" to continue this activity. This is called a "shadow activity."

Increased connectivity was also found in the central sulcus of the brain, which is located at the boundary between the motor and the sensory centers. The neurons in this area are not only activated when the body is active, but also when you think about being active. For example, thinking about running produces very similar changes in this region to those which occur when actually running.

The neural changes remained for the five days after the novel was complete. At this point the study stopped, leaving the duration of their persistence an open question at present.

“The neural changes that we found associated with physical sensation and movement systems suggest that reading a novel can transport you into the body of the protagonist,” Berns says. “We already knew that good stories can put you in someone else’s shoes in a figurative sense. Now we’re seeing that something may also be happening biologically."

The use of fMRI scans to study changes associated with experience offers a number of interesting possibilities. One of the more interesting to me is the possibility of increasing the strength of the effect using transcranial direct current stimulation or transcranial magnetic stimulation. It would be fascinating (or frightening) if the reading of a book could be transformed to a real-seeming experience in an internally visualized fantasy world.

Source: Emory University