A cool new study with chilly implications from a team led by the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) has shown for the first time that ice can generate electricity in two surprising ways.

We encounter ice all the time, even in the hotter regions of the Earth. It comes as tiny icicles and giant glaciers, a slippery coating that makes pavements hazardous, frost clogging a poorly tended freezer, or (if you're me) floating in a Scotch and soda. It all seems very familiar, but ice has many surprising properties. To name a few, it expands when it freezes, absorbs a remarkable amount of heat before melting, and it comes in over 20 crystalline forms.

However, one thing that most of us don't expect to find is that ice can generate electricity – not the least because it's such a good insulator. However, according to the UAB team, ice can not only produce electricity, it can do so in two distinct ways.

Those who managed to stay awake in science class may recall learning about piezoelectricity, where materials like quartz generate electricity when put under pressure. This is because the crystals that make up quartz and similar materials have a non-symmetrical structure that gives them an in-built polarity. That means when you apply uniform pressure to quartz, you get electricity.

Ice is different. In its common hexagonal crystal form, there is no polarity when it is in bulk. Give it a squeeze and nothing happens. This is because even though the individual H₂O molecules have polarity, with the oxygen atom acting as a negative pole and the hydrogen atom as a positive, the molecules that make up the ice crystals cancel each other out, so no juice.

What the researchers in Barcelona noticed was that things change when, instead of compressing ice, you bend it. This produces a non-uniform strain on the ice, producing what is called strain gradient. That is, where one side of the ice is compressed and the other side stretched. This causes a separation of the positive and negative charges on the microscopic level that, on the macroscopic scale, comes out as electricity.

Not surprisingly, this is known as flexoelectricity. It's not much. Say, about 1.14±0.13 nC/m, but it is measurable.

The team also found that when ice is cooled down to 160 K (-113 °C, -171.40 °F), the ice starts acting like a magnet when it comes to electricity. At such extreme temperatures, a thin layer on the surface of the ice exhibits ferroelectricity. That is, it responds like magnetic iron to a reversing electric field by developing natural electrical polarization, like flipping the poles on a magnet.

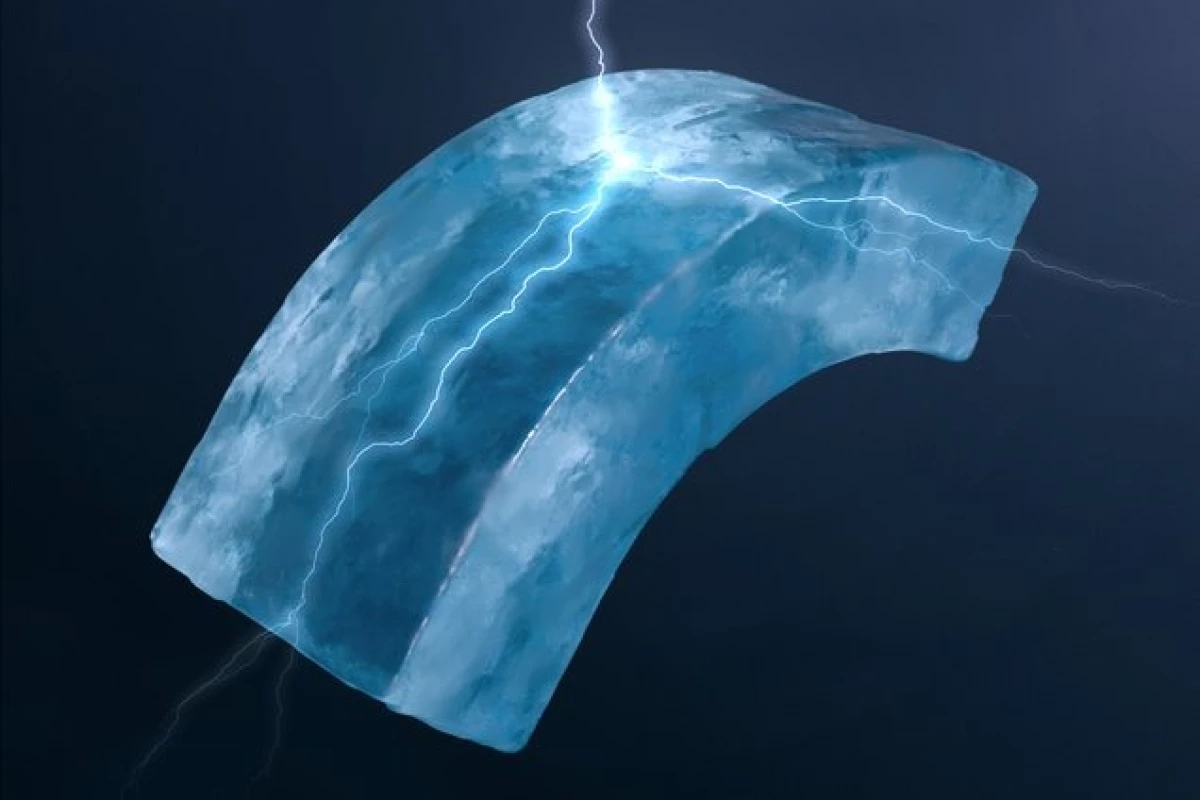

According to the team, this phenomenon is more than a bench-top curiosity. One of the most spectacular of weather events is a lightning storm. Impressive as one of these is, scientists are still not entirely clear as to how a big cloud of water vapor can suddenly turn so violent and start hurling lightning bolts like Zeus on a bad day.

The best explanation is that it has to do with colliding ice crystals in a cloud turning it into a giant Van de Graaff generator, but the mechanism is still unclear. The team speculates that this newly discovered electric ice might be part of that mechanism.

If nothing else, it's a tidbit you can bring out that will stop any conversation about the weather being cold.

The research was published in Nature Physics.

Source: UAB