Future data centers might do away with banks of hard drives and switch to a storage medium that nature has been using for billions of years – DNA. In a major step towards making that a reality, scientists have created a new system of reading and organizing files using microcapsules.

Like many things humans have built, nature beat us to data storage with a system vastly superior to anything we could come up with. DNA packs information in incredibly densely – a single gram of the stuff can hold up to 215 petabytes, or 215 million GB of data, meaning the entire contents of the internet could be kept in a shoebox full of DNA. Recent work has even found ways to double that data density by adding new letters to the alphabet soup.

Plus, DNA can be extremely long-lasting. Our current hardware tends to degrade within decades, but under the right conditions DNA could potentially be preserved for millions of years. And finally, it requires far less energy to maintain, cutting the power bills that massive data centers are running up.

But of course, there’s a catch. Writing data to DNA and reading it back are fiddly, costly processes that can damage the DNA itself and introduce errors. But now a new breakthrough could help make the whole system more practical.

Currently, retrieving data from DNA is done using a technique called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). DNA strands containing data are all swimming around freely in a kind of soup, with each strand tagged with a specific sequence that acts like a file name. When you need a certain file, a matching primer is used to search the goop and attach to the required DNA strand. This DNA is then copied millions of times so that the system can find it and read the file. The problem is, this degrades the original data each time you read it, and it becomes difficult to read multiple files at once.

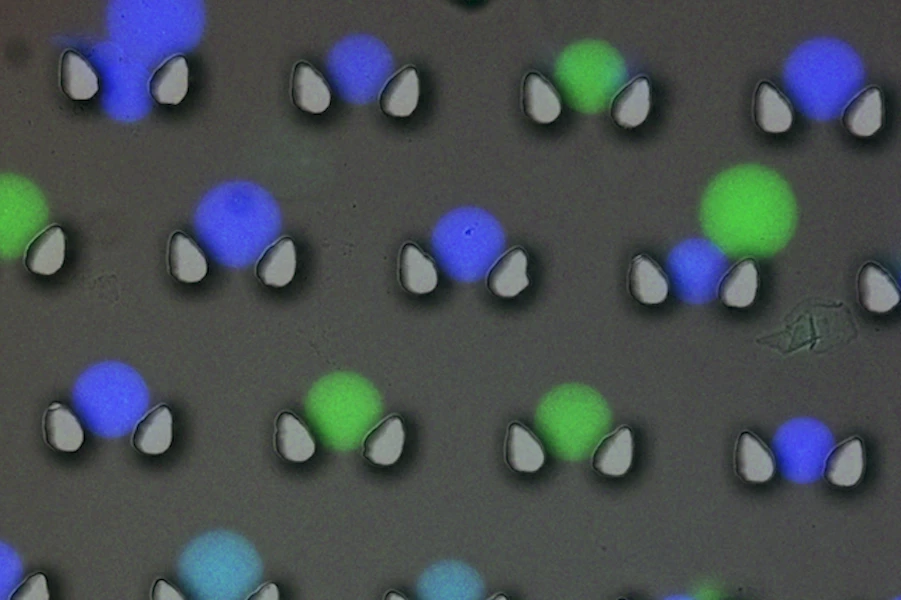

To get around that issue, the researchers encase the DNA in microcapsules made of proteins and a polymer, with one file anchored into each capsule. When heated above 50 °C (122 °F), the capsules seal themselves up, so that the PCR copying can only affect each file separately. When the temperature is lowered again, the copies detach while the original remains anchored.

That means the original file’s quality doesn’t degrade with each read, greatly reducing errors. The team says the system could read up to 25 files at the same time, and lost only 0.3% of a file after three reads rather than 35% with existing methods.

To make the system easier to search, the scientists gave each file a fluorescent label and each capsule its own color, allowing data to be categorized, separated and sorted. Ultimately, the team envisions a data center where information is encoded onto DNA in one area, while robotic arms can select individual capsules, read the data and put them back.

“Now it’s just a matter of waiting until the costs of DNA synthesis fall further,” said Tom de Greef, lead author of the study. “The technique will then be ready for application.”

The research was published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.