You can learn a lot about someone by the way they walk – and apparently that even applies after 10,000 years. In New Mexico, researchers have discovered what they claim is the longest known set of fossilized human footprints, stretching over 1.5 km (0.9 mi) – and they tell an amazing story.

The footprints were preserved in a playa – a dried up, ancient lakebed – in White Sands National Park in New Mexico, US. The area is well known for being dotted with hundreds of thousands of footprints from various Ice Age animals, including mammoths, giant sloths, saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, bison, camels, and of course humans.

And it’s the tracks of that lattermost animal that caught the researchers’ attention here. Not only are they the longest known trail of fossilized human footprints ever found, but they’re so well preserved that the scientists can infer a surprising amount of detail about the story behind them.

Writing in The Conversation, the researchers explain that the person who left them was most likely a woman, but perhaps an adolescent male. They were carrying a small child, they were in a hurry, and after a few hours they doubled back and made a return journey – without the child. And they weren’t alone out there.

The researchers can tell who made the prints by their small size. Their walking speed can be estimated by the distance between the prints – the track maker was walking at more than 1.7 m (5.6 ft) per second, which is much faster than a comfortable walking speed of between 1.2 and 1.5 m (3.9 and 4.9 ft) per second. The tracks also extend in more or less a straight line, indicating the human was heading somewhere specific.

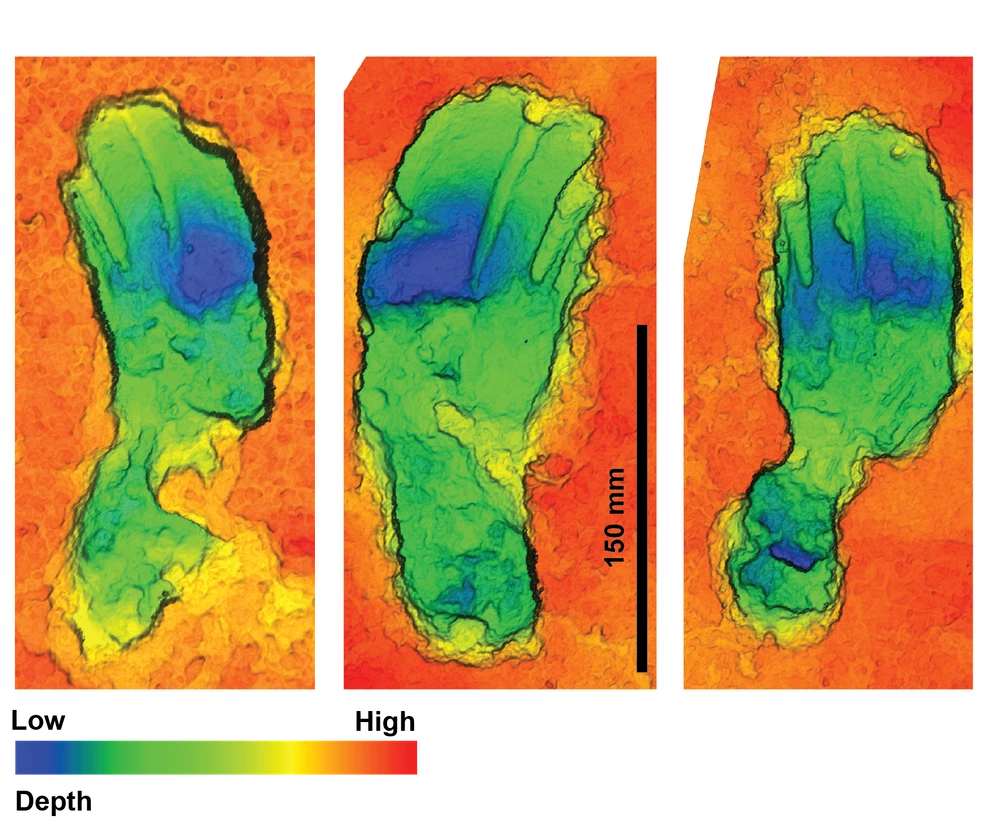

Tracks left by a small child also appear alongside the main tracks at different points, as though the person carrying them stopped to put them down every now and then. From their size, the child was probably no more than two years old. The researchers can even see the effects of when the adult was carrying the child too – those prints have more of a “banana shape” as the adult’s foot slides and rotates outwards under the extra weight.

Intriguingly, there’s a second set of tracks going in the opposite direction, which appear to have been made a few hours after the first trip. These ones are narrower and more uniform, which suggests that the adult was travelling alone this time.

What happened to the child? That part of the story is impossible to tell from footprints, which sets the imagination working overtime. Our inclination towards the dramatic makes us fear that something happened to them, but of course it’s probably far more mundane. Maybe the adult was returning the child to their mother, or perhaps the pair just got caught in a sudden downpour.

Either way, it appears other animals were out and about that day. The tracks are intersected by two sets of animal footprints, which seem to have been made between the outgoing and return journeys.

At one point, a mammoth crossed the human tracks. Judging by the fact that they’re just a straight unbroken line, it seems like the animal didn’t notice nor pay any attention to the recent presence of humans.

The second animal, however, was a bit more cautious. At another point, giant sloth tracks are seen crossing the humans’ path, but the prints suggest it reared up on its hind legs, as if to catch the scent. It turned and trampled the human tracks, then dropped back to all fours and headed off. That implies it understood the danger that humans posed.

It’s quite amazing that such a detailed story can be inferred from some 10,000-year old footprints. We’ll never know exactly what this journey was all about, but it’s endlessly fascinating to wonder.

The research was published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

Sources: National Park Service, The Conversation