A team of scientists from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) led by geographer Peter Fretwell has used satellite imagery of penguin poop captured by ESA's Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission to calculate that there are 20 percent more emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica than previously thought.

Standing 100 cm (39 in) tall and weighing up to 45 kg (99 lb), one would think that a giant black and white bird like the emperor penguin would be a doddle to count against the snowy wastes of coastal Antarctica, but it isn't as simple as that. Aside from being dark for much of the year, Antarctica has some of the most inhospitable terrains and weather in the world, with temperatures where the emperors live plunging to -50 °C (-58 °F), so surveys are very difficult to conduct. It also doesn't help that the emperors breed during the dark of the winter.

To overcome this, the BAS team turned to the Copernicus Sentinel-2 as a way of seeking out previously uncharted penguin colonies from orbit over the past decade. Though the emperor penguins are much too small to be seen even with a resolution of 10 m/pixel, the large, brown stains of penguin droppings, or guano, show up very well.

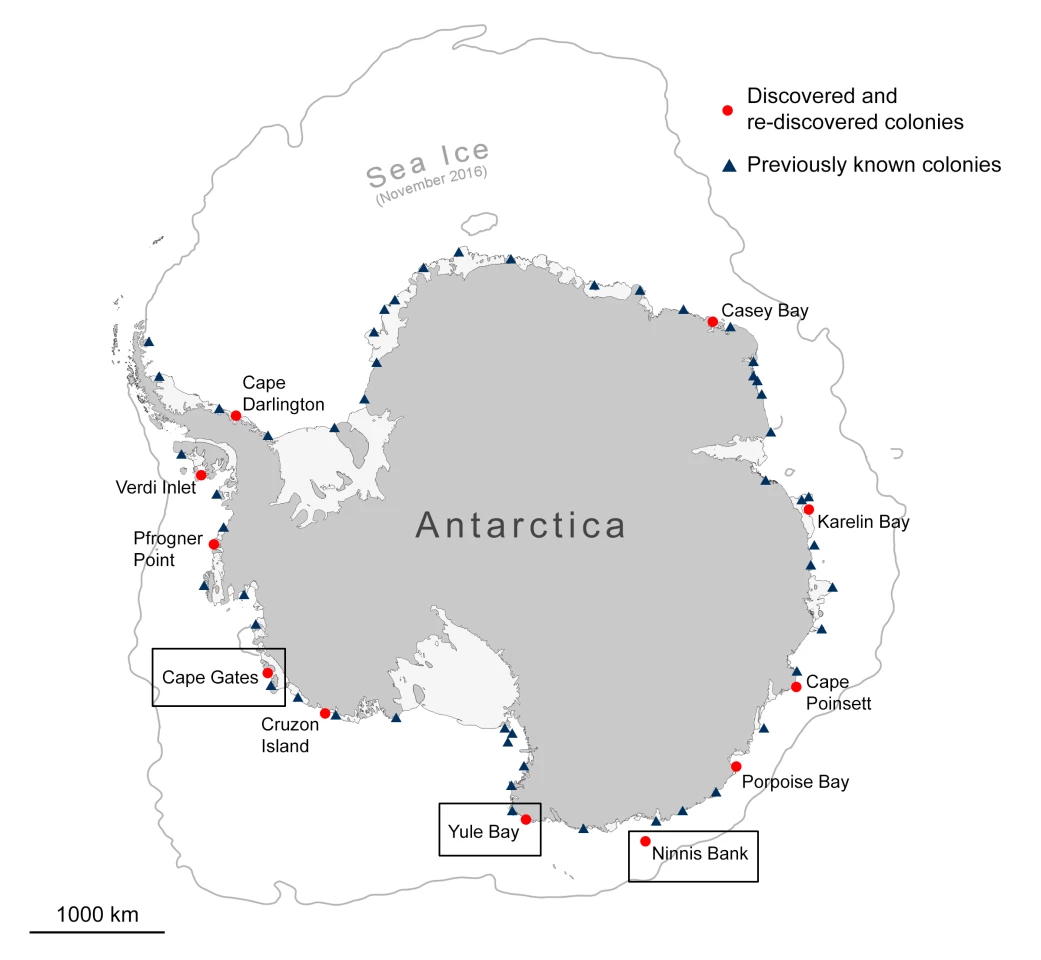

As a result, the team has found 11 new colonies, bringing the total to 61 around the continent and increase the overall population count to over half a million, or 265,500 to 278,500 breeding pairs. This is only about a five to 10 percent increase on previous estimation because the colonies are so small.

According to BAS, the additional penguins are welcome, but there is still cause for concern due to the birds living and breeding on ice floes, which are vulnerable to melting in a warming climate. Some of the colonies were found as far as 180 km (112 mi) from the coast of the polar continent.

"Whilst it is good news that we’ve found these new colonies, the breeding sites are all in locations where recent model projections suggest emperors will decline," says Philip Trathan, Head of Conservation Biology at BAS. "Birds in these sites are therefore probably the 'canaries in the coal mine' – we need to watch these sites carefully as climate change will affect this region."

The findings were published in Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation.

Source: ESA