The giant iceberg A-68a is likely to ground itself in the shallows of South Georgia island, so a scientific expedition is getting ready to visit the site to determine the impact of the event on the local ecology using underwater glider robots.

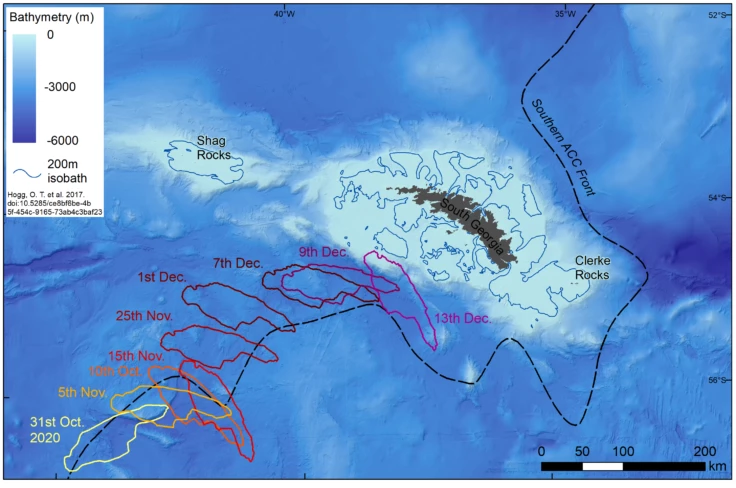

In November 2020, the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) announced that images returned from Copernicus Sentinel-1 and other satellites indicated that the 1,550-square-mile (3,900-sq-km) A-68a, which had broken away from the Antarctic ice shelf in 2017, was drifting toward South Georgia Island.

At the time, there was a strong possibility that the iceberg would either break up substantially or be shifted off course by the ocean currents and miss the island. However, as tracking continued, A-68a remained on an intercept course and is now about 60 miles (97 km) offshore of South Georgia and in waters that are only 250 feet (76 m) deep. That's pretty shallow for an iceberg to drift through.

South Georgia is one of the world's largest Marine Protected areas and is famous for its marine and shore life, most notably its colonies of seals and penguins. The fear is that if the iceberg runs aground, it could disrupt the birds' and animals' feeding patterns; plow up the seabed and destroy communities of sponges, brittle stars, worms, and sea-urchins; release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and flood the surrounding sea with fresh water.

In addition, aerial images collected by the British Ministry of Defence show that the iceberg continues to break up, which could pose a danger to shipping in the area. However, it will also bring mineral dust to the South Georgia waters, which can act as fertilizer for plankton, so there is a potential plus side.

To better understand the impact, BAS scientists and others will sail for South Georgia in late January 2021 from the Falkland Islands on the National Oceanography Centre’s (NOC) ship RRS James Cook. Aboard will be a pair of Slocum robotic underwater gliders that will spend four months taking measurements of seawater salinity, temperature, and chlorophyll from opposite sides of the iceberg. These 5-foot (1.5-m) autonomous craft operate untethered via a satellite link and can propel themselves for months at a time by changing their buoyancy. As they do so, their wings convert this upward or downward movement into forward motion.

"Autonomous submarine gliders are an excellent, cost-effective, and sustainable means of gathering and recording important marine data," says Steve Woodward, the NOC’s Glider Technical Lead. "In this case, we will program the [National Marine Equipment Pool] gliders to get as close to the edge of the iceberg as we feel is safe and practicable, and collect the data that will be needed to enable the team to understand the implications of what is taking place with A-68a."

The video below discusses the mission.

Source: British Antarctic Survey