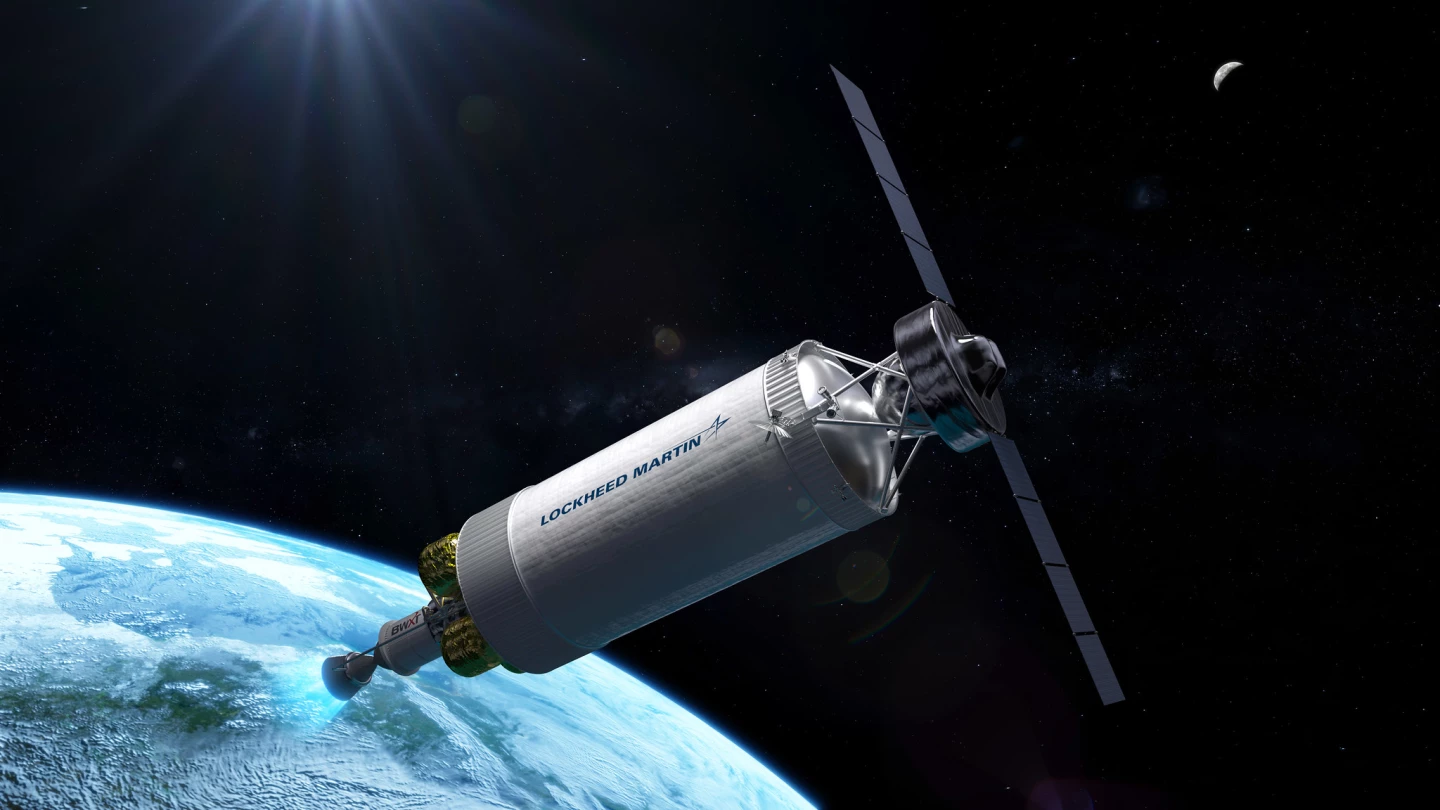

The first crewed mission to Mars may get there and back a bit faster and safer if a contract DARPA has awarded to Lockheed Martin bears fruit. The contract is to rapidly advance and fabricate a nuclear thermal rocket engine scheduled to fly by 2027 for cislunar and deep space missions.

In a remarkably short time, humanity has gone from learning how to fly a heavier-than-air craft to sending robotic probes into interstellar space. The surprising thing is that the chemical rocket engines used then, and are still used now, reached the edge of their theoretical limits in 1942, just as they made their first successful flights.

Since then, rockets have become larger and more effective, but these improvements cannot get past the inherent limitations of the basic technology in regard to thrust and efficiency. What this means is that a crewed mission to Mars is about as far as chemical rockets can take us – and only at great expense for a voyage that could take years.

First conceived of shortly after the Second World War, Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) engines promise thrust slightly greater than that of chemical engines along with up to five times higher efficiency. This would make a Mars mission much shorter and allow the crew the option of an in-mission abort. It would also make missions to build and supply a Moon base cheaper and safer.

DARPA's Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations (DRACO) project aims at demonstrating a new engine technology based on a nuclear reactor fueled with a special High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU). When operating, the reactor would heat cryogenic hydrogen into an extremely hot gas that would be directed through a rocket nozzle to generate thrust.

According to DARPA, DRACO would not be used to lift off from Earth. Instead, it would be part of the upper-stage payload and would remain turned off until the vehicle reaches a safe orbit. Under the new contract, Lockheed, in partnership with BWXT Advanced Technologies, will rapidly advance the technology and begin manufacturing in anticipation of the 2027 flight.

"These more powerful and efficient nuclear thermal propulsion systems can provide faster transit times between destinations. Reducing transit time is vital for human missions to Mars to limit a crew's exposure to radiation," said Kirk Shireman, vice president of Lunar Exploration Campaigns at Lockheed Martin Space. "This is a prime technology that can be used to transport humans and materials to the Moon. A safe, reusable nuclear tug spacecraft would revolutionize cislunar operations. With more speed, agility and maneuverability, nuclear thermal propulsion also has many national security applications for cislunar space."

The video below discusses the NTP vehicle.

Source: Lockheed Martin