If you've been wondering how long the day on Uranus is, you probably need to get out more. But if you have, you'll be interested to know that observations by the Hubble Space Telescope have shown that it's 28 seconds longer than previously thought.

If you really want to annoy an astronomer, ask them to figure out how long a day is on Uranus.

On planets like Earth or Mars, calculating how long they take to rotate on their axis is relatively easy. They're solid bodies with visible surface features that can be easily seen at telescopic distances, so careful observation and a bit of calculation readily gives an accurate answer. If you can't see the surface, like on Venus, you can still use radar to track the surface as it turns. Even with Jupiter, which is engulfed in a vast atmosphere, there are giant storms that can act as markers.

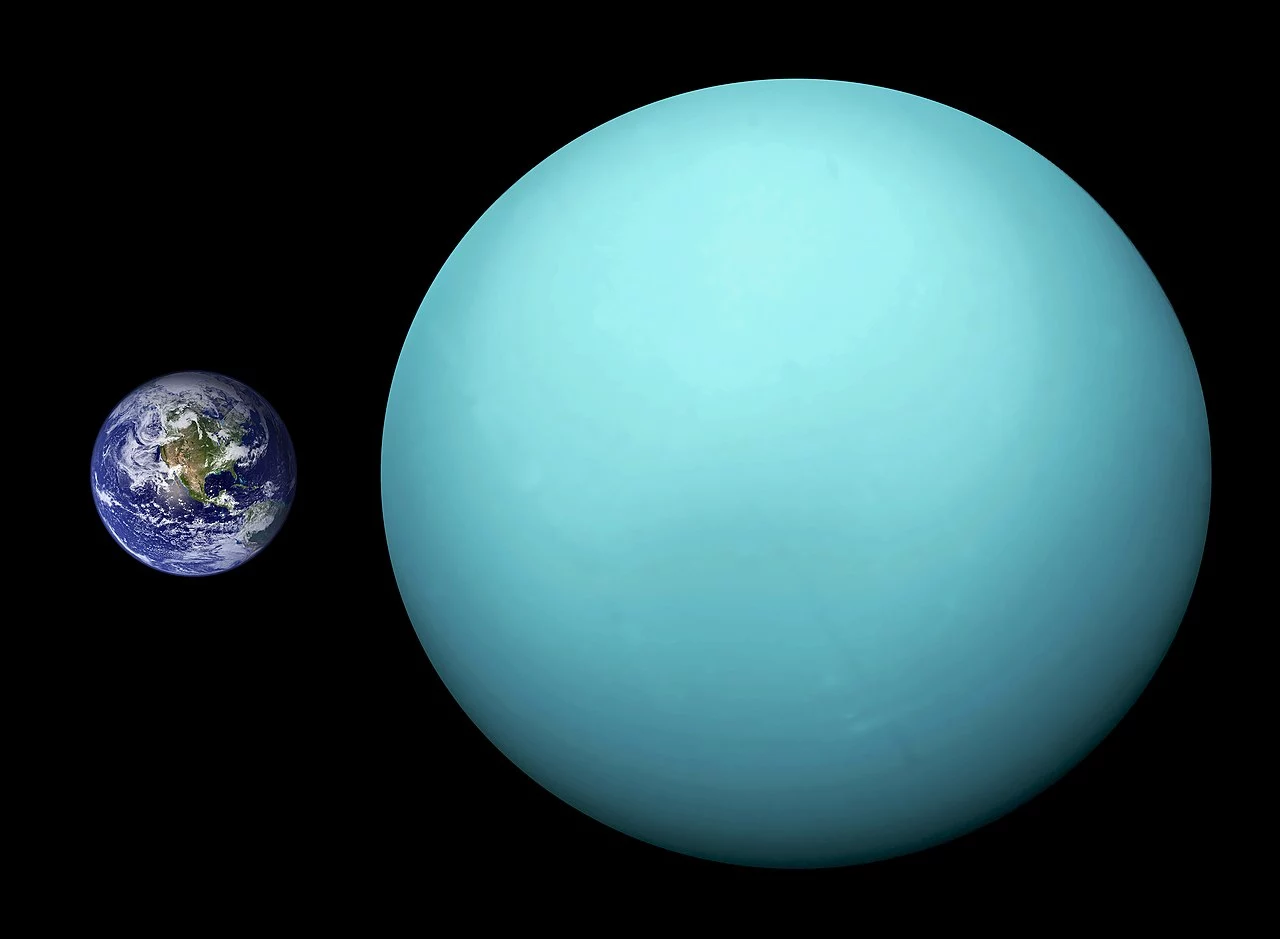

Uranus is another matter entirely. About 63 times the size of Earth, the planet is only slightly denser than water. That's because it's a gas giant composed mainly of hydrogen and helium with ices of water, ammonia, and methane mixed in. In visible light, its upper atmosphere is a featureless expanse of bland pale-blue. Beneath this, there's nothing like a solid surface. Instead, the atmosphere gets progressively denser and hotter until it blurs into a sort of liquid that may or may not have a tiny rocky core at the center.

This makes calculating the length of a Uranian day hard enough, but it's further complicated by Uranus being tilted at 98 degrees on its axis, so it's essentially rolling on its side, with the poles getting more sunlight than the equator. That causes atmospheric patterns that could be used as markers to change seasonally and erratically. Worse, the atmosphere at the equator rotates at different speeds than at the poles.

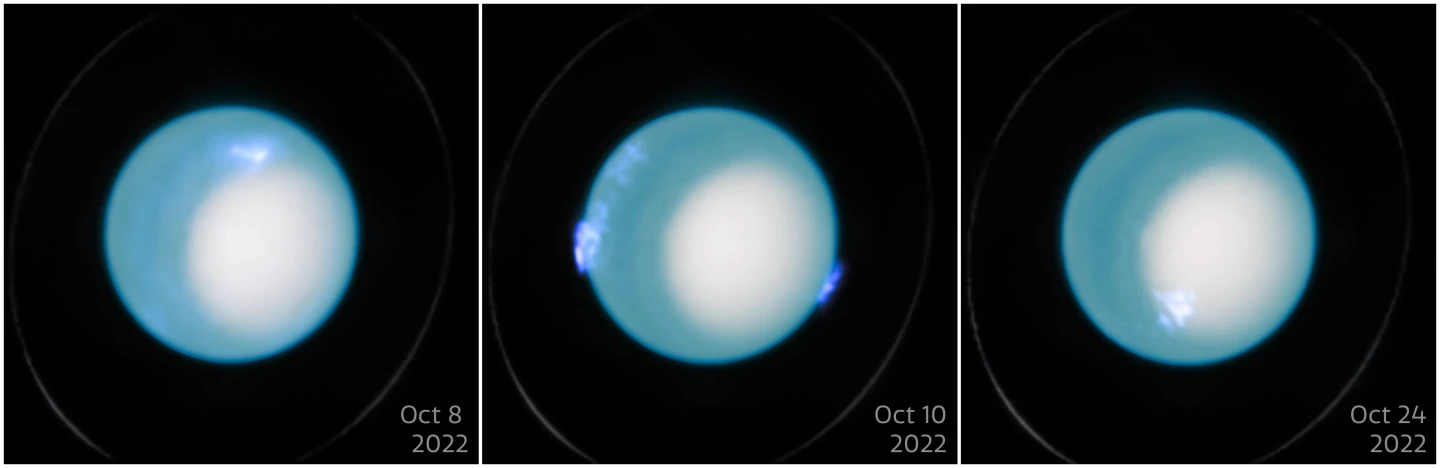

To overcome these problems, a team of scientists led by Laurent Lamy used ultraviolet images collected by the Hubble Space Telescope between 2011 and 2022 to track auroras on Uranus.

As with Earth, Uranus has a magnetic field that shields it from cosmic radiation, but at the magnetic poles, where the magnetic lines of force converge, energetic particles can reach the atmosphere and cause spectacular auroras to appear. These not only produce cool images, they also give scientists a marker to track the rotation of Uranus with 1,000 times better accuracy. However, this takes a lot of observations because, like Earth, the Uranian magnetic poles tend to drift.

The upshot is that we now know that a day on Uranus takes 17 hours, 14 minutes, and 52 seconds, or 28 seconds longer than the best previous estimate made by NASA’s Voyager 2 during its 1986 flyby.

"Our measurement not only provides an essential reference for the planetary science community but also resolves a long-standing issue: previous coordinate systems based on outdated rotation periods quickly became inaccurate, making it impossible to track Uranus’ magnetic poles over time," said Lamy. "With this new longitude system, we can now compare auroral observations spanning nearly 40 years and even plan for the upcoming Uranus mission."

The research was published in Nature.

Source: ESA