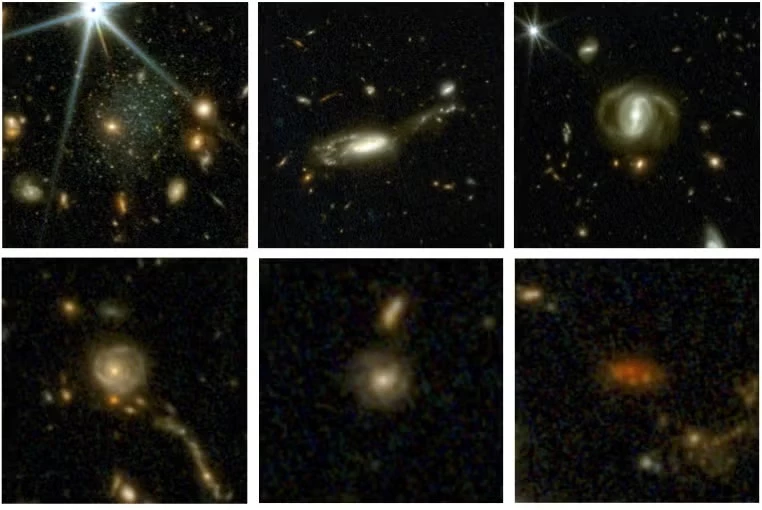

For years, astronomers have been working to piece together the story of our universe, but the critical early chapters remained largely incomplete. Our telescopes simply haven't been sensitive enough to pick up those faintest traces of light from the farthest reaches of the universe. Until now that is. A new collaborative project dubbed the COSMOS-Web field has compiled the most comprehensive cosmic map ever, including images of the early universe as far back as 13.5 billion years.

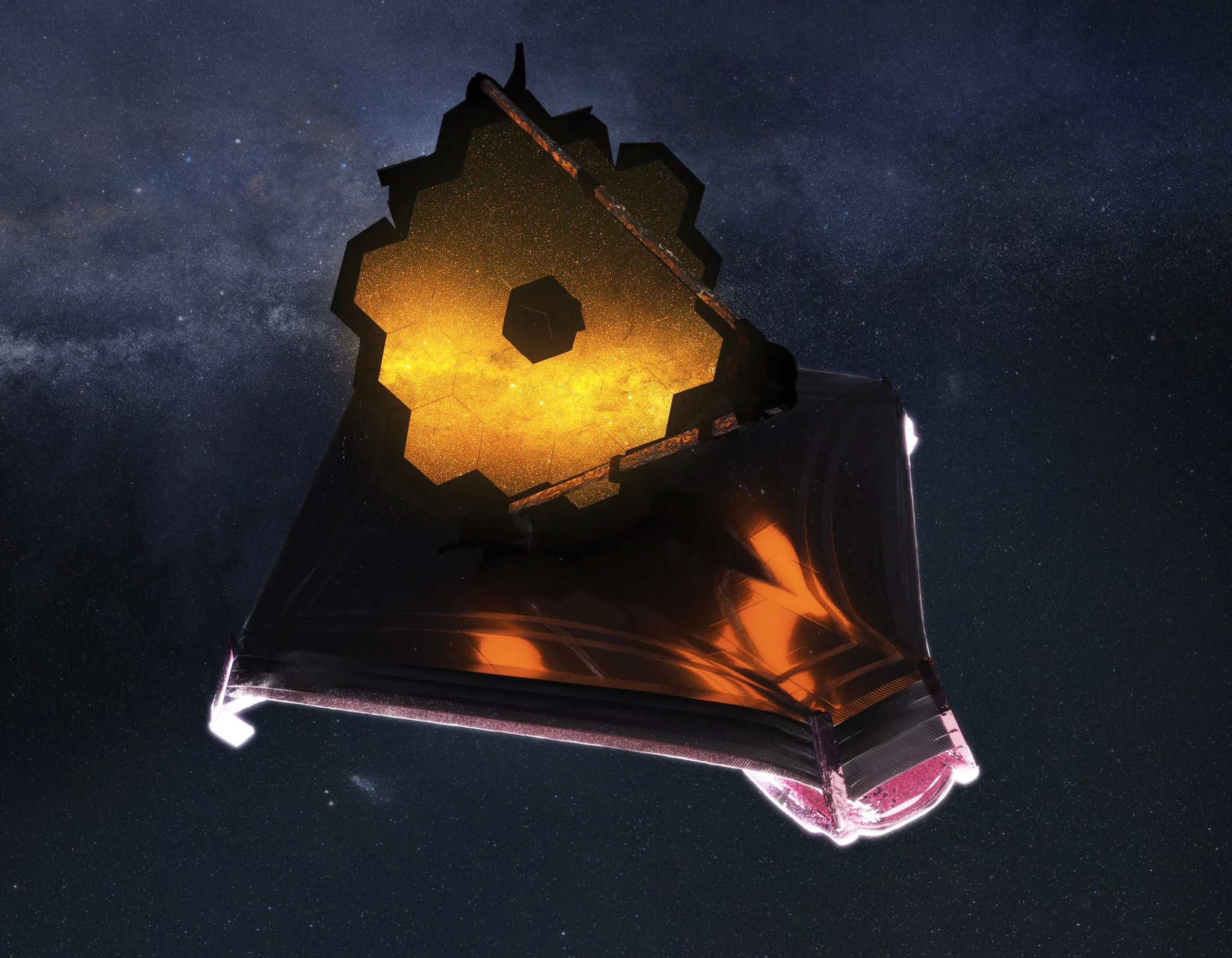

By using the data from the James Webb Space Telescope’s 6.5‑meter (21-ft) mirror, scientists at UC Santa Barbara have surveyed 0.54 square degrees of sky, which is equivalent to the area of three full moons when viewed from Earth. Charting nearly 800,000 galaxies, the COSMOS-Web dataset covers almost 98% of cosmic history.

“Our goal was to construct this deep field of space on a physical scale that far exceeded anything that had been done before,” said the co-leader of the COSMOS collaboration and UC Santa Barbara physics professor Caitlin Casey.

Thanks to JWST, positioned in space beyond the Earth’s atmosphere, and its sensitivity to capture these weak photons, researchers gathered a vast amount of raw data. However, interpreting this raw data required specialized knowledge and powerful computers. The COSMOS team spent over two years turning these raw images into user-friendly accessible catalogs.

Now, these interactive images are out and freely accessible for all to explore. Users can directly zoom in on the objects to check their properties or search images for specific objects.

“The sensitivity of JWST lets us see much fainter and more distant galaxies than ever before, so we’re able to find galaxies in the very early universe and study their properties in detail,” said Jeyhan Kartaltepe, the lead researcher of COSMOS-Web and professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “The quality of the data still blows us away. It is so much better than expected.”

What’s more interesting is that researchers glimpsed 10 times more galaxies than expected. The team even encountered a few supermassive black holes, previously invisible to the Hubble telescope. These surprises raised a heap of new questions about what was happening in the first few hundred million years of our universe.

“Since the telescope turned on we’ve been wondering ‘Are these JWST datasets breaking the cosmological model?' Because the universe was producing too much light too early; it had only about 400 million years to form something like a billion solar masses of stars," explained Casey. "We just do not know how to make that happen. So, lots of details to unpack, and lots of unanswered questions.”

The objective behind the project isn’t just to see galaxies at the beginning of time, but also to get a wider view of the environment that existed in the early days. With the entire dataset open to the public, the team hopes the fresh eyes, as well as graduate and undergraduate astronomers, will uncover something new and unlock clues about cosmic mysteries like dark matter and the physics of the early universe.

“The best science is really done when everyone thinks about the same data set differently,” Casey said. “It’s not just for one group of people to figure out the mysteries.”

Sources: UC Santa Barbara, Rochester Institute of Technology