Scientists have discovered the second site at which ESA’s ill-fated Philae lander touched down on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, and in so doing revealed that the ancient ice hidden under the surface of the comet is softer than the froth on a cappuccino. The second impact site saw the lander gouge out the shape of a human face on the barren landscape, which has led to the area being nicknamed "skull-top" ridge.

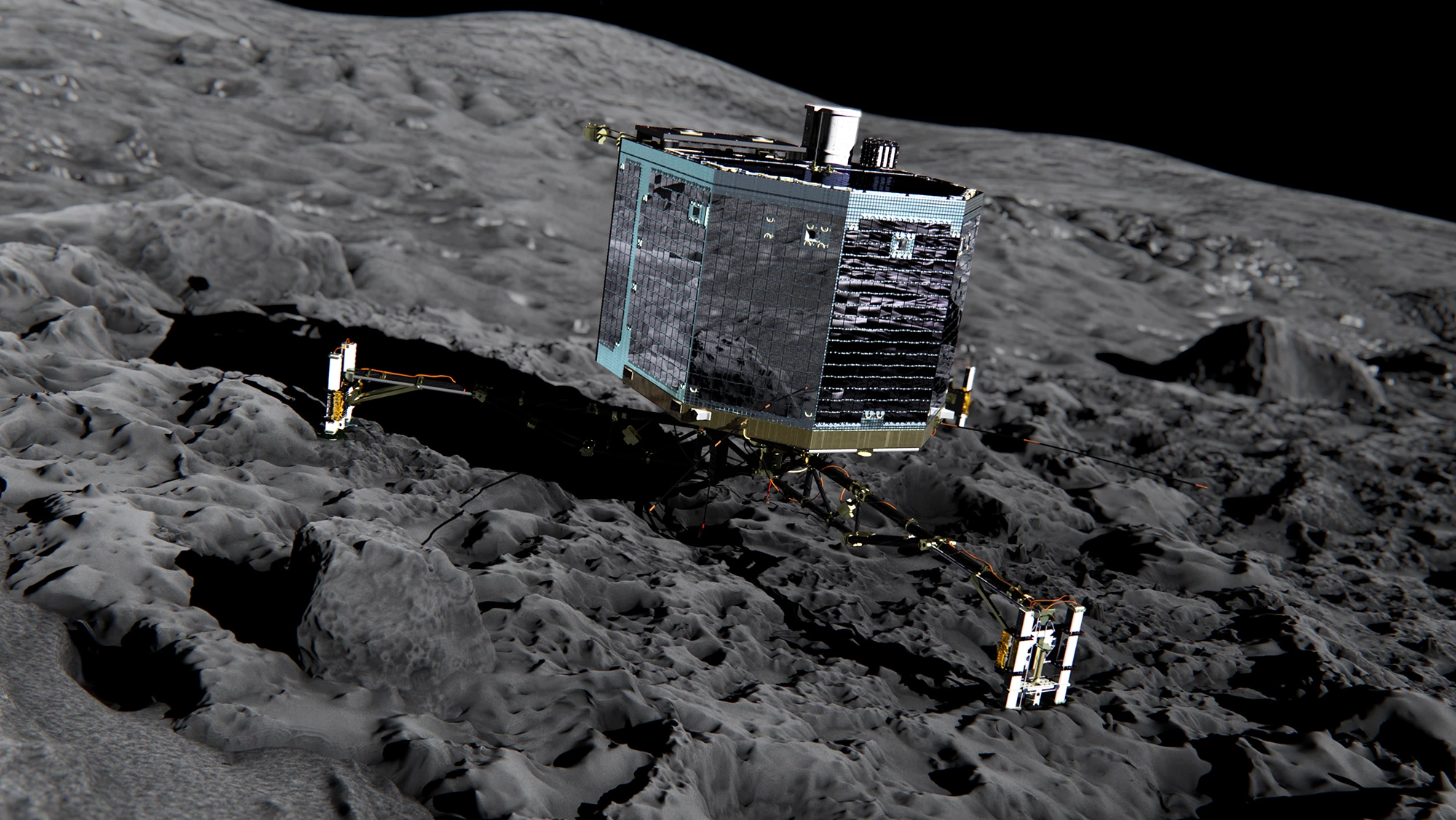

ESA's great comet-chasing mission is unquestionably one of its greatest space accomplishments to date. The orbital Rosetta probe captured the imagination of science enthusiasts the world over as it succeeded in becoming the first spacecraft to enter orbit around a comet, and proceeded to collect a multitude of data that transformed our understanding of these wandering relics.

However, the science yield could have been even greater had the Philae lander, which had hitched a ride with Rosetta through the bleak environment of interplanetary space, managed to stick its landing on 67P. Sadly this was not to be the case.

On November 12, 2014, the Philae lander was directed to descend to the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, and upon making contact fire harpoons that would anchor the little explorer to the dusty surface.

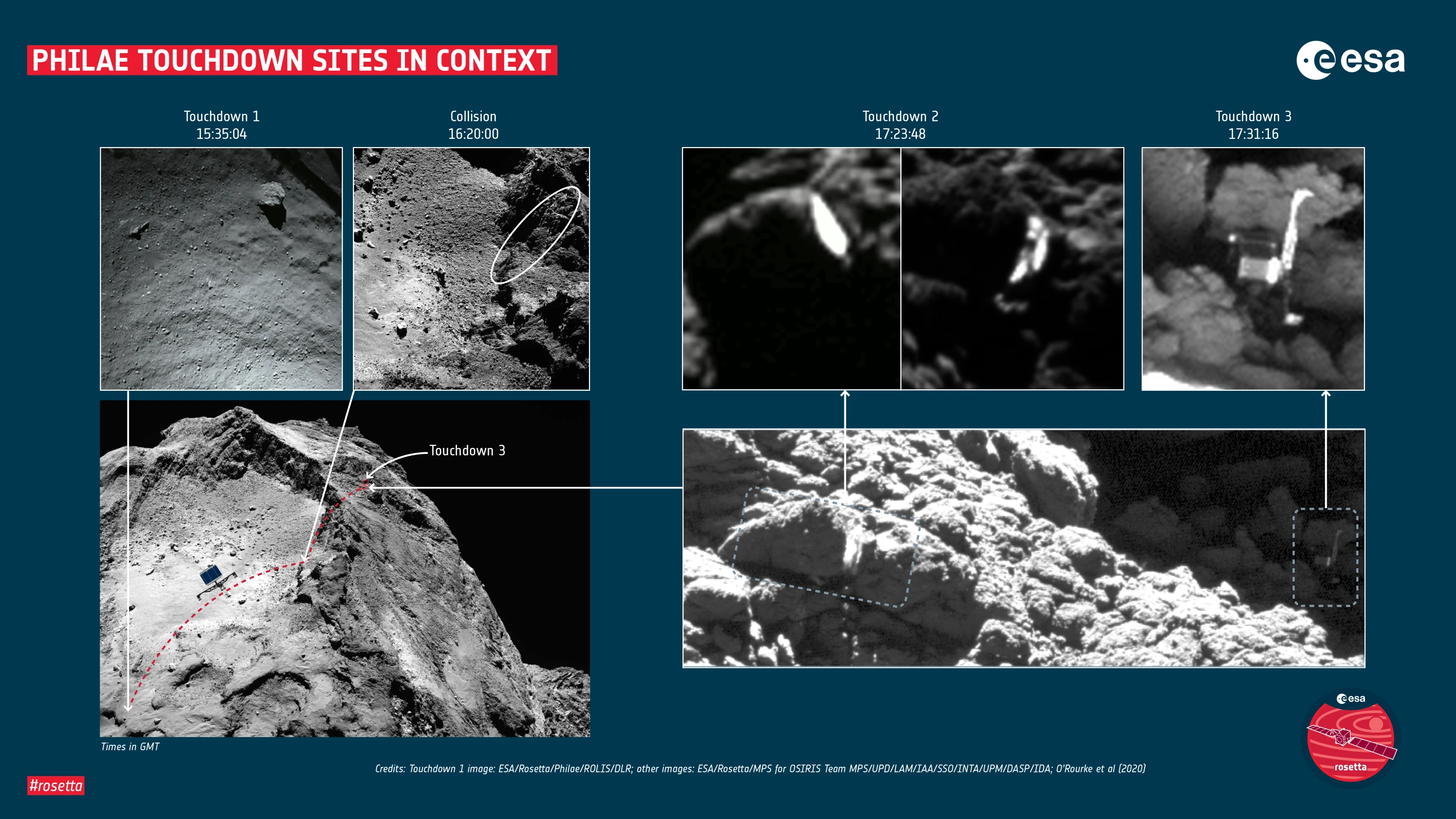

But when it actually came to securing the lander to the comet, Philae’s anchoring system failed to fire, causing the probe to bounce off 67P on a two-hour flying journey before finally touching down on the comet once more and ricocheting to its eventual resting site.

Thankfully the probe was able to collect and transmit enough data to complete its primary mission before its battery drained. However, members of the scientific community have been keen to discover exactly where, and what happened when Philae made landfall for the second time.

Data transmitted from Philae’s sensors had suggested that the lander had dug deep into the comet’s surface, potentially uncovering deposits of ancient ice that had been hidden for billions of years.

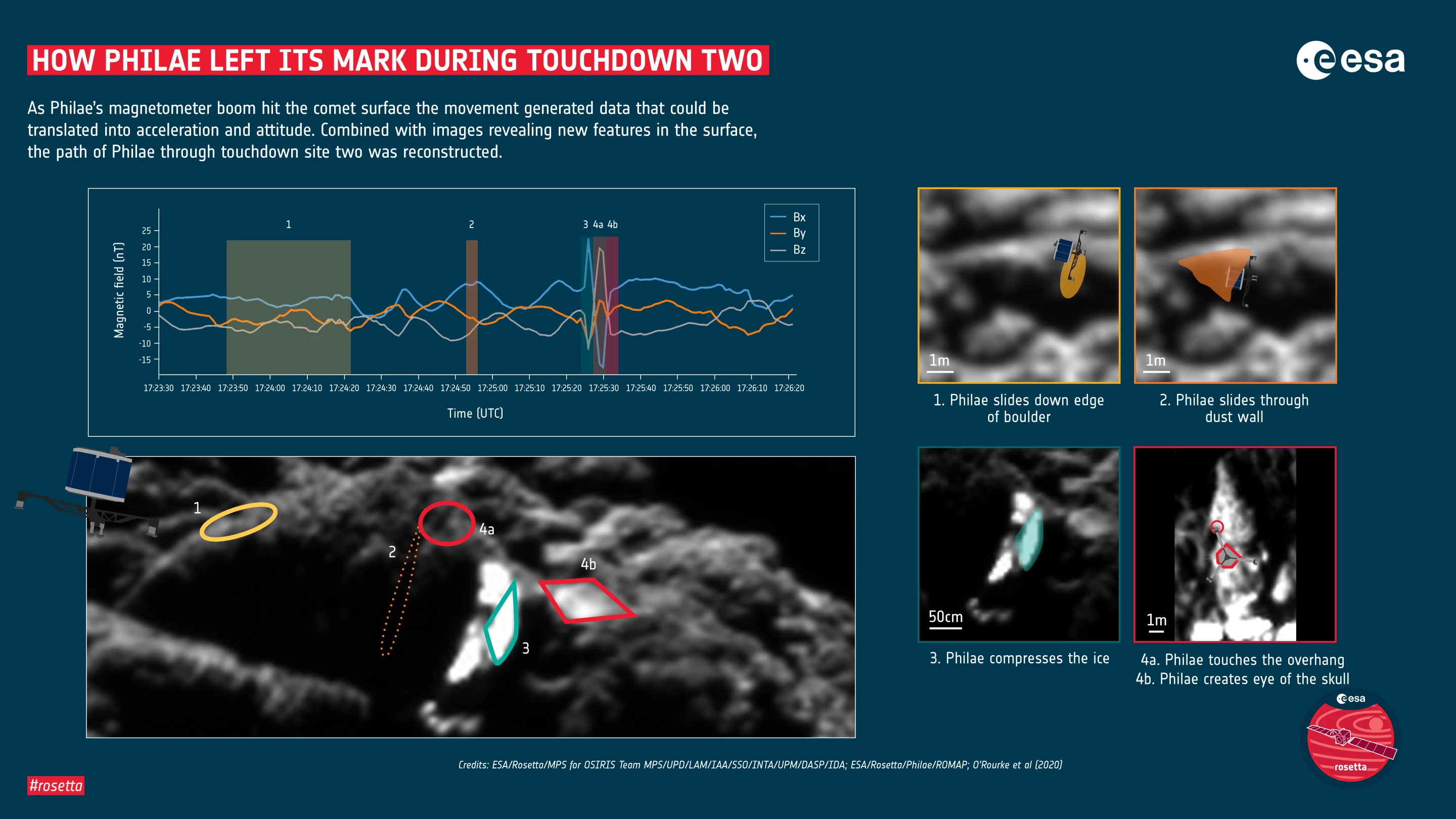

A team of scientists set about combining information from both the Rosetta spacecraft and Philae lander in an attempt to discover the wayward probe’s second impact point.

The scientists were able to pinpoint 3.5 m (11.5 ft) worth of bright, exposed water-ice that marked the second site in high-definition imagery captured by Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera. However, it was Philae’s magnetometer boom that really helped the team piece together exactly what had happened after the point of contact.

Philae’s Rosetta Lander Magnetometer and Plasma Monitor (ROMAP) instrument was designed to study 67P’s local magnetic field, and how it interacts with the solar wind. Part of the instrument took the form of a boom that protruded 48 cm (18.9 in) from the shell of the lander.

The researchers were able to examine data that detailed how the boom moved as it struck the surface in order to figure out how long the lander was pressed into the surface, and how fast it was moving when it made contact with the terrain around it. This data was compared to Rosetta’s own magnetometer to discern Philae’s attitude as the second "landing" unfolded.

According to the data sleuthing, Philae spent two minutes at the second touchdown site after hitting the surface, during which time it hit the terrain four times. One particularly hard hit saw the probe embed itself 25 cm (9.8 in) into the surface, leaving imprints of the drill tower in its wake.

“The shape of the boulders impacted by Philae reminded me of a skull when viewed from above, so I decided to nickname the region ‘skull-top ridge’ and to continue that theme for other features observed,” commented Laurence O’Rourke, a member of the Rosetta/Philae science team. “The right ‘eye’ of the ‘skull face’ was made by Philae’s top surface compressing the dust while the gap between the boulders is ‘skull-top crevice’, where Philae acted like a windmill to pass between them.”

On a practical note, the impact data also revealed that the ancient material hidden below the surface of the comet had a porosity of around 75 percent, and was incredibly soft.

According to Laurence, “The simple action of Philae stamping into the side of the crevice allowed us to work out that this ancient, billions-of-years-old, icy-dust mixture is extraordinarily soft – fluffier than froth on a cappuccino, or the foam found in a bubble bath or on top of waves at the seashore.”

The study has been published in the journal Nature and the video below highlights the skull-like shape carved out by Philae during its second assault on comet 67P.

Source: ESA