The European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter is set to have a chance encounter with the two tails of the disintegrating Comet ATLAS over the coming days. The spacecraft is currently en route to the inner solar system for a close pass with the Sun, and has had four key scientific instruments rushed through commissioning in order to be ready for the unexpected rendezvous.

The Solar Orbiter was designed to endure multiple close encounters with our star, during which it will characterize the Sun and the inner heliosphere using a suite of 10 scientific instruments. At the time of the Solar Orbiter’s launch at 05:03 CET on February 10, mission operators had no idea that the spacecraft was on a rendezvous course with the tail of Comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS).

The lucky coincidence didn’t come to light until earlier this month, when Geraint Jones of the UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory discovered that the probe was going to pass 44 million km from Comet ATLAS, and could actually encounter its diffuse tails from as early as May 31. Jones notified the European Space Agency, and wrote a short paper detailing the pass and its potential science implications with fellow authors, which appeared in the journal Research Notes of the AAS on May 5.

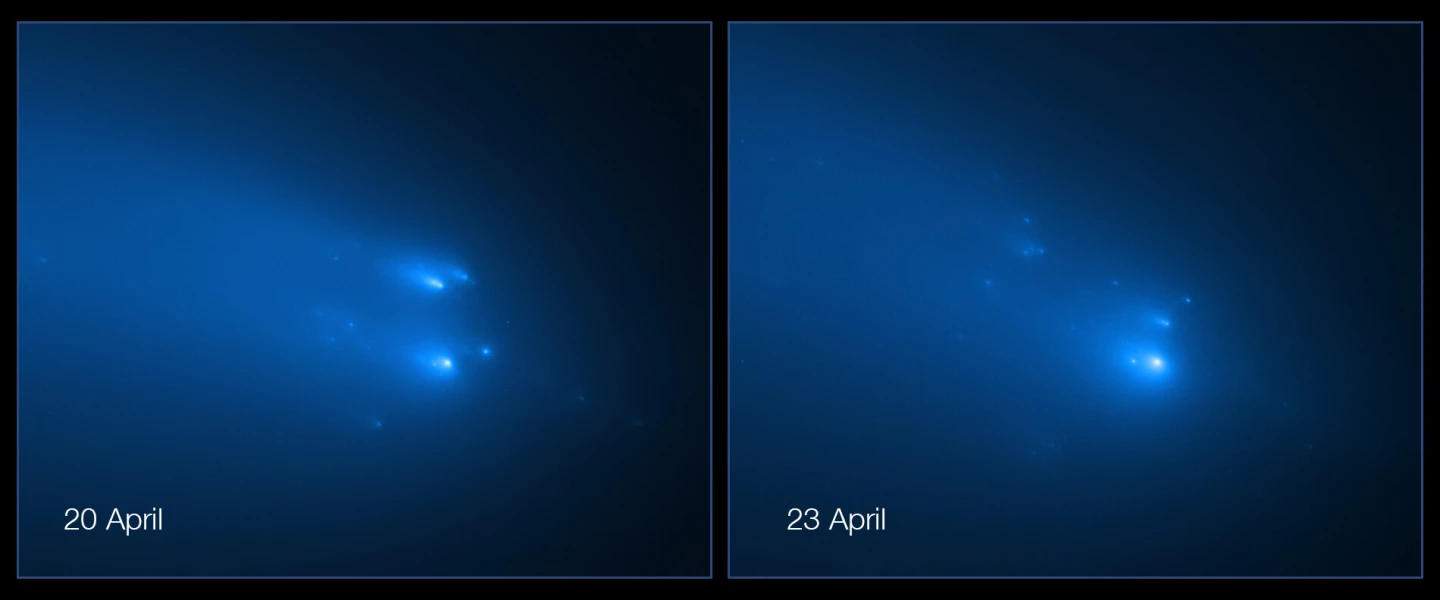

Comet ATLAS was observed to brighten significantly after its discovery on December 28, 2019, leading some to believe that the hunk of cosmic material could even become visible to the naked eye.

However, the comet subsequently grew dimmer, and in early April the nucleus was observed fragmenting into several smaller pieces. It broke into even smaller chunks in mid-May, highlighting the fragility of the icy solar system bodies.

ATLAS could still survive to make its closest pass to the Sun – which is well within the orbit of Mercury – on May 31, at which point it will be 37 million km from our parent star. However, it is likely to throw off less dust and gas than some scientists were hoping, which in turn will make the doomed cosmic wanderer less visible.

Thankfully, the Solar Orbiter will get one last chance to get to know ATLAS before it disintegrates entirely.

The four instruments that will be used to examine Comet ATLAS’s tails were not due to be fully commissioned until June 15, however, thanks to a special effort made by ESA scientists and engineers they will all be switched on and harvesting data during the encounter.

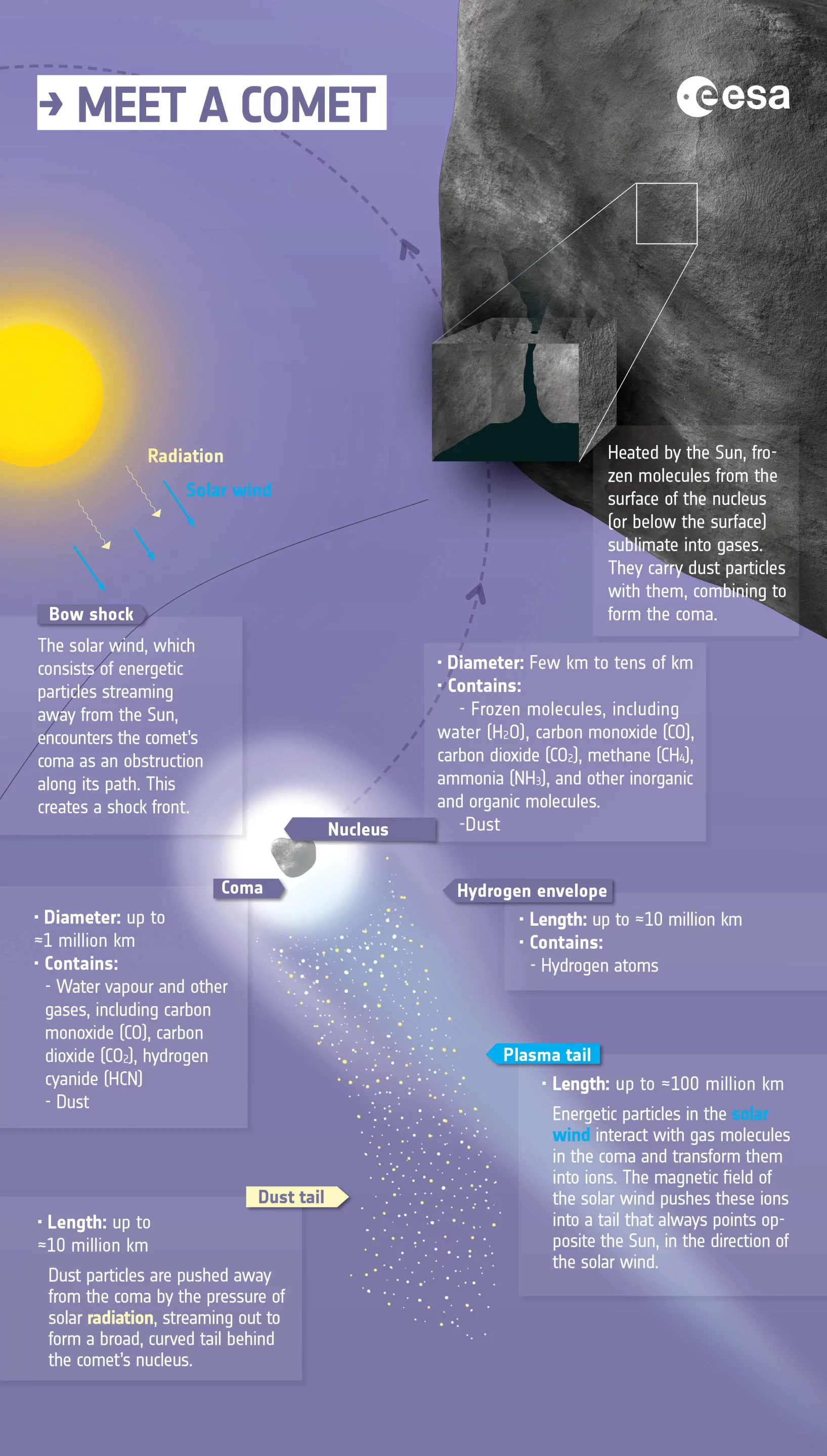

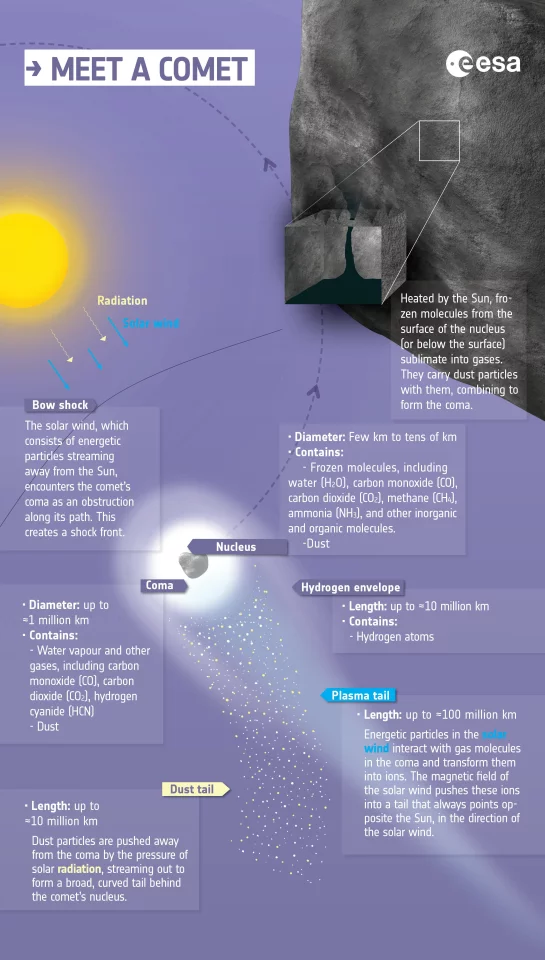

Comets are a significant contributor of particle debris to the inner solar system. By taking readings as the orbiter passes through the trail, scientists could gain vital information that will help them understand the dusty environment surrounding our star.

The Solar Orbiter will pass in to ATLAS’s ion tail – which points directly away from the Sun – on May 31, and will emerge a day later on June 1. The probe will then encounter the physical trail of the comet, which is made up of particles of dust and gas, a few days later on June 6.

The success of the venture will depend largely on the density of the comet’s tails. During the pass, the probe’s Solar Wind Analyzer will attempt to detect variations in the interplanetary magnetic field that result from interactions with ions streaming out from the comet.

If enough particles are present, there is also a chance that some could strike the orbiter itself. The high-velocity impact would instantly vaporize the particles, and give rise to a cloud of electrically charged gas that could then be analyzed by the spacecraft’s Radio and Plasma Waves instrument.

Finally, the Solar Wind Analyzer instrument will attempt to actually capture some of the particles belonging to the tail of the wandering loner.

Only six previous missions that were not specifically designed to hunt down a comet have ever been known to pass through one of their tails. These close approaches were only discovered when scientists combed through mission data after the fact. The lucky rendezvous with Comet ATLAS represents the first time that such a pass will have been known of, and prepared for, beforehand.

Once its comet-snooping work is complete, the Solar Orbiter will continue inwards towards a scorching rendezvous with the Sun. The closest approach for its first stellar rendezvous is set to take place on June 15, at which point the spacecraft will pass 42 million km from the Sun’s "surface."

"With each encounter with a comet, we learn more about these intriguing objects. If Solar Orbiter detects Comet ATLAS's presence, then we'll learn more about how comets interact with the solar wind, and we can check, for example, whether our expectations of dust tail behavior agree with our models," explains Jones. "All missions that encounter comets provide pieces of the jigsaw puzzle."

Source: ESA