From Fukushima to the darkest corners of the ocean, robots built for extreme environments and an appetite for discovery continue to enlighten our understanding of places too dangerous to tread. Those launched into deep space may be the most daring examples, continually pushing the limits of human ingenuity and expanding our understanding of the universe. In this series New Atlas will be profiling space probes, both past and present, tasked with pushing the boundaries of science by leading us into the great unknown. This week: a spacecraft developed under a veil of Soviet secrecy to survive the surface of Venus.

Name: Venera 7

Launched: 1970

Subject of study: Venus

Current location: On Venus, in some form

As our next-door neighbor and the focus of science fiction writers imagining a world beneath the cloud tops brimming with jungles, oceans and dinosaurs, Venus held a certain allure for astronomers throughout the 20th century. When American probes began skimming past the planet during the early stages of the space race, they quickly put to rest any hopes of an inhabitable environment, but this did little to deter a secretive Soviet ambition to get up close and personal with the second planet from the Sun.

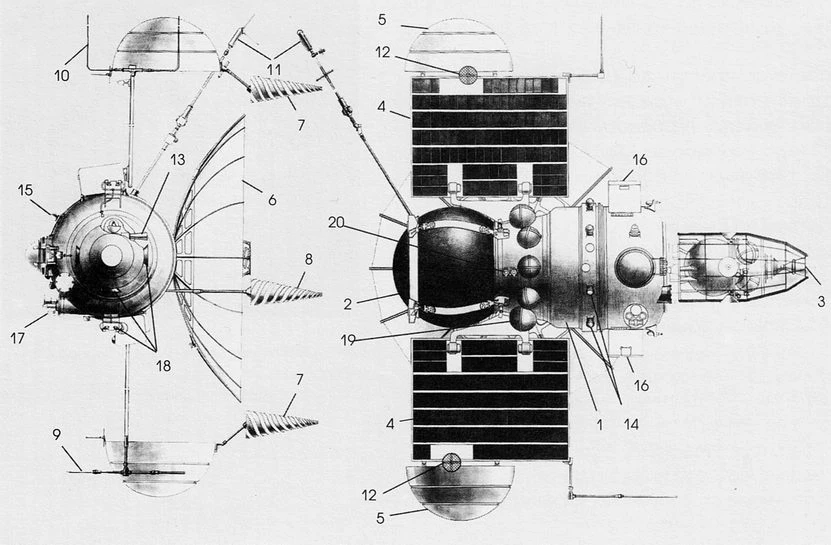

Venera, (Russian for Venus), was the name given to the series of space probes the Soviet Union built between 1961 and 1984 to study Venus, both its surface environment and atmosphere. This meant some were designed to observe it from afar and some were designed to land on the planet’s surface, a feat that had never been accomplished at the program’s outset.

Venera 1VA was the Soviets Union’s first attempt to visit Venus in 1961 and failed to leave Earth orbit, though the world was not to know that at the time. The country’s preference was to keep its space exploits in-house until they amounted to success, and so the failed Venera 1A mission was publicly given the name of “Heavy Sputnik,” an apparent successor to the world’s first artificial satellite famously launched in 1957.

While the probes to immediately follow the doomed Venera 1A are believed to have actually reached Venus, their telemetry failed long before then. It wasn’t until 1967 and the launch of Venera 4 that the Soviet Union began to reap some reward for its efforts. That probe became the first spacecraft to relay data back to Earth from another planet’s atmosphere, before it crumbled under the intense pressures on Venus’ surface soon after.

A couple more atmospheric probes would follow, until the Soviets got serious about building a spacecraft to withstand the harsh realities of life on Venus. This meant engineering a machine to endure pressures of 180 atmospheres and temperatures of 540° C (1,004° F).

Venera 7 was constructed as a single spherical shell using titanium and lined with shock-absorbing materials. This, the Soviets hoped, would enable the lander to survive the landing and remain on Venus, from where it could continue to relay new information about its surroundings.

Weighing 490 kg (1,080 lb), the probe was a sizeable one for the time and was actually launched alongside an identical aircraft in August 1970, the Kosmos 359, which didn’t make it beyond Earth orbit. Venera 7, however, successfully reached its target planet four months later, thanks to a couple of course corrections along the way.

Slipping into the nightside atmosphere on December 15 of that year, Venera 7 deployed its 2.5-sq-m (26.9-sq-ft) parachute at an altitude of 60 km (37 mi) with the intention of drifting safely down to the surface. Six minutes in, the parachute ripped. Twenty-nine minutes later, the probe smashed into the surface of Venus at a speed of around 60 km/h (37.3 mph), which was not part of the plan, but not entirely fatal to the mission either.

Venera 7 managed to survive this impact, and to even relay a full-strength signal for one second before failure. But computer processing of the radio signals at a later date revealed that the toppled-over Venera 7 probe continued to transmit a weak signal for a full 23 minutes after impact. Data revealed a temperature of around 475° C (878° F) at the surface, along with a pressure of 92 bar and wind speeds of 2.5 meters per second (5.6 mph).

This was the first time a spacecraft had ever transmitted data back to Earth from another planet, a momentous achievement but just a harbinger of scientific discovery on part of the Soviet Union’s Venera probes. In 1975, during a 53-minute transmission, Venera 9 sent back the first ever pictures of another planet’s surface, stunning scientists with its abundance of sharp-edged rock formations.

“Even the moon does not have such rocks,” Soviet scientist Boris V. Nepoklonov said in an interview with local broadsheet newspaper Izvestia in response to the imagery. “We thought there couldn't be rocks on Venus, they would all be annihilated by erosion, but here they are, with edges absolutely not blunted. This picture makes us reconsider all our concepts of Venus.”

In 1982, Venera 13 joined the party and would perhaps return the biggest scientific loot of the Venera probes. This included panoramic photographs and the first ever color photos of another planet’s surface. It also drilled into the surface and analyzed the soil inside an airlock using an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer.

Three more probes were launched as part of the Venera program until it wrapped up in 1984, including a final pair of orbiting spacecraft to map the surface. Other spacecraft from different agencies have since flown by and orbited Venus for various purposes, but we haven’t been back to the surface since.

For more on pioneering space probes, you can check out last week's instalment of "Into the great unknown" on NASA Parker Solar Probe here. Next week, we look at the first spacecraft to take on Saturn and its spectacular ring system.