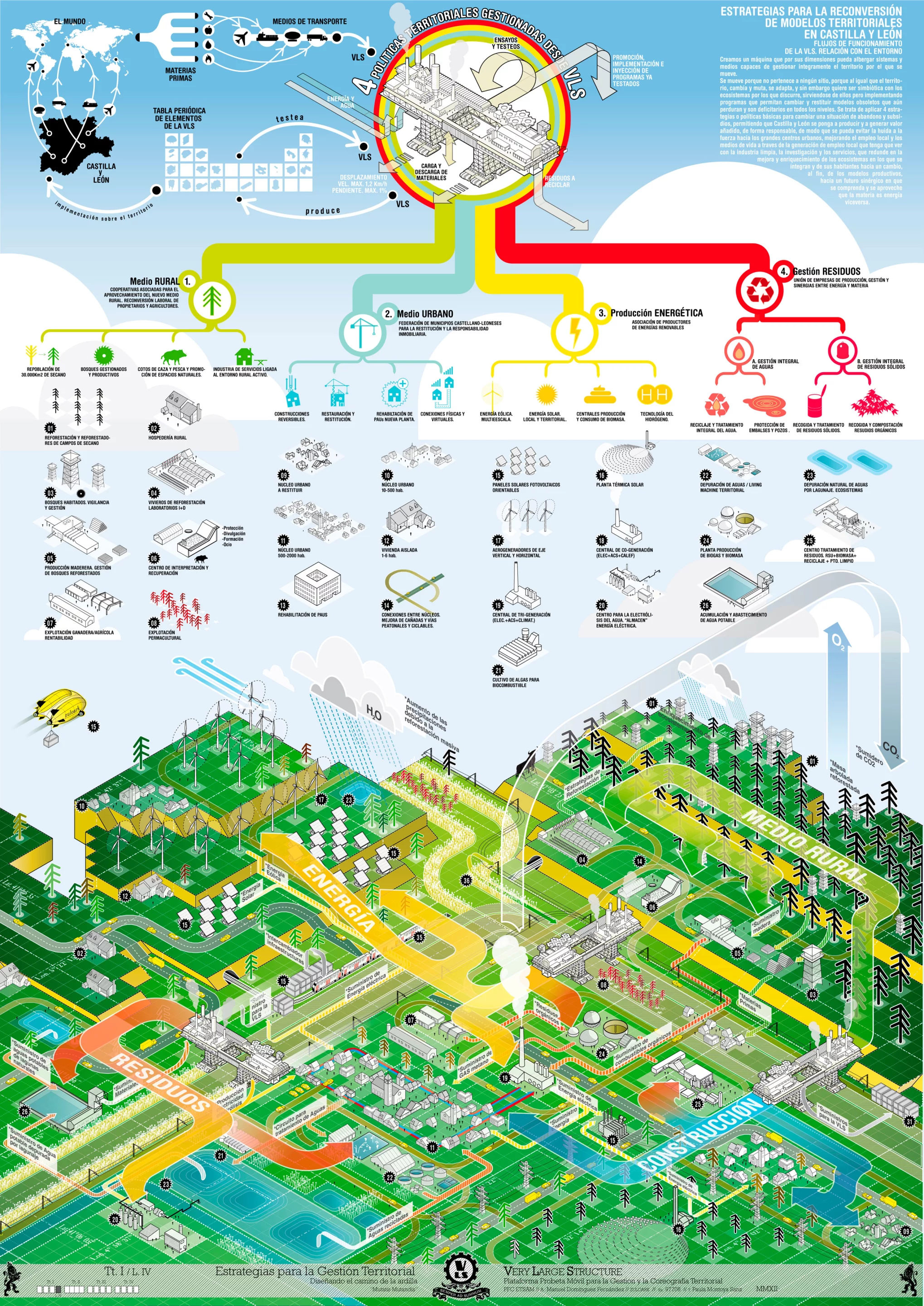

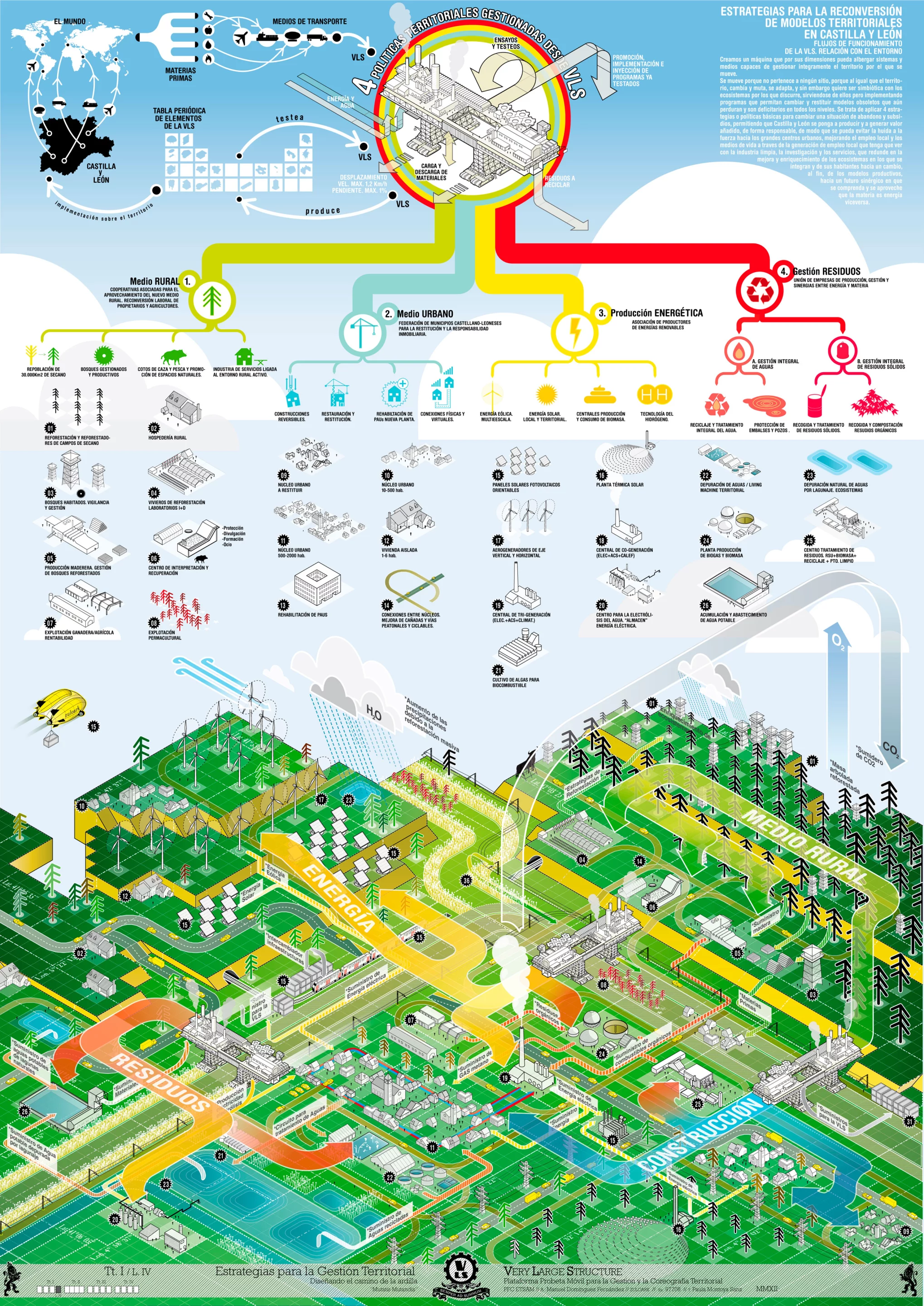

Of all the questions one might like to ask Manuel Domínguez about his architecture thesis project, why he called it Very Large Structure is probably low on the list. Domínguez' concept depicts compactly planned cities atop vast mobile structures, capable of crawling to new locations as the needs or desires of the populace dictate. The idea clearly recalls Ron Herron's Walking City essay for Archigram in 1964, and though Domínguez cites that as an inspiration, he says it's just one among many. Real-world technology seems to have been the main influence.

Clearly, clearly, VLS is a highly improbable scheme. Yet Domínguez asserts that it is feasible because of its basis in established technology, though to that he candidly adds that he's "not sure if it's desirable."

Looking at the illustrations, some of those influences are easy to spot; others less so. Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages..." as well as robotics. To that list he adds less tangible influences: "political anomalies, self-generated architecture and urbanism, ludic architecture and engineering..."

But Domínguez has obviously drawn from contemporary culture, and speaks of an attraction to "science fiction [...] utopical and dystopical architecture, urbanism, cinema, literature, [and] manga." Science fiction and cinema perhaps stand out most from the list, especially judging by the Death Star in the background of one of the visualizations. The giant caterpillar tracks of VLS recall vast vehicles such as NASA's crawler-transporters and Bagger 293, but also the fictional sandcrawler of the original Star Wars. Perhaps VLS borrows from 20th Century Fox almost as much as it does 20th century tech. (Herron's city (PDF) was supposed to literally walk, by the way, being a city on articulated legs).

That this is such a bold speculative design is partly borne out of Domínguez' frustrations with the theses of architecture finals, which he describes as "an exercise of nonsense [...] because it's so directed and closed that at the end everybody does almost the same exercise." Instead, Domínguez chose a "self-concious" project, "one that could fit all the obsessions I've been accumulating since I was I child." Job done, I think.

Sources: Manuel Dominguez, Zuloark

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/107a100/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1645x3255+0+0/resize/1455x2880!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-4.jpg)

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/b2cf81d/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1496x932+0+0/resize/1496x932!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-8.jpg)

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/86373b9/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1200x546+0+0/resize/1200x546!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-13.jpg)

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/40e2378/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1200x1063+0+0/resize/1200x1063!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-16.jpg)

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/174000b/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2750x3883+0+0/resize/2040x2880!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-25.jpg)

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/997f49f/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2750x3889+0+0/resize/2037x2880!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-30.jpg)

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/beab3b6/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1750x2458+0+0/resize/1750x2458!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-35.jpg)

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/2041d0e/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3500x1651+0+0/resize/2880x1359!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-40.jpg)

![Domínguez points out that much of it has been available since the 1960s: "open-air mining machinery, shipyard installations, logistic and management in super-ports and super vessels, big scale infrastructures and transport, space technology, [and] eco-villages" (Image CC BY-SA Manuel Dominguez)](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/5f075db/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3000x2250+0+0/resize/2880x2160!/format/webp/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farchive%2Fvery-large-structure-walking-city-48.jpg)