While "traditional" objects may exhibit varying degrees of glossiness in different areas, 3D-printed items are typically uniformly shiny all over. That could be about to change, however, thanks to a new printer designed at MIT.

When it comes to controlling the glossiness of 3D-printed objects, conventional printers are limited by the nozzles in their print head. Although the openings in the ends of those nozzles allow the molten plastic building material to easily pass through, they can get plugged by viscous, sticky varnish.

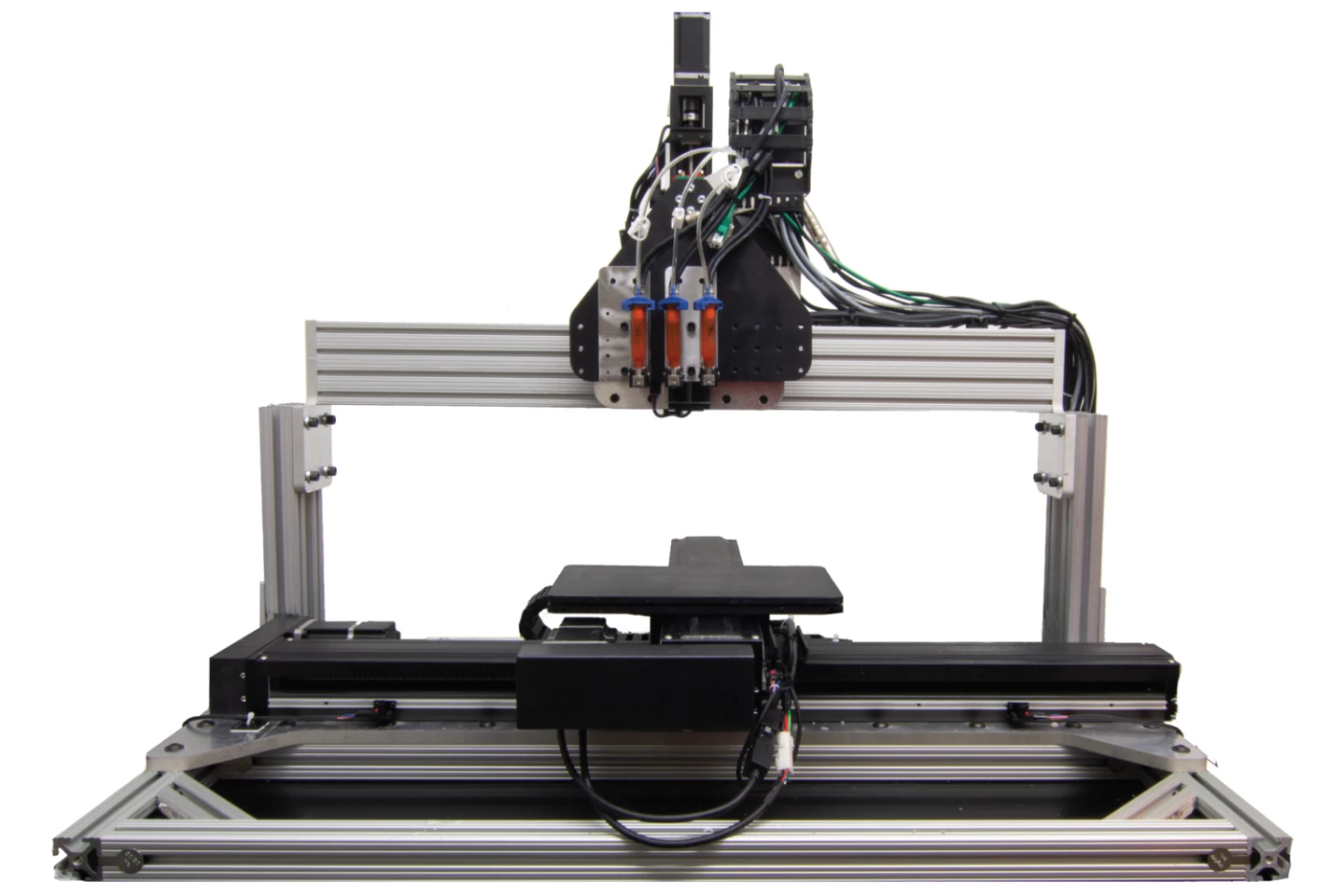

Led by mechanical engineer Michael Foshey, a team of MIT researchers partially addressed this problem by creating a prototype 3D printer with larger nozzles. That said, they still wanted to keep the varnish droplets that were sprayed out of those nozzles relatively small.

This was accomplished by tweaking the pressure of the reservoirs which store the three types of varnish within the printer, and by adjusting the rate at which a needle valve in each nozzle moves to release the droplets. Additionally, it was found that by varying the velocity of the sprayed droplets, it was possible to control the size of the spots that the droplets form when hitting the printed object's surface – basically, faster-travelling droplets form larger spots.

Varying degrees of glossiness are achieved by switching back and forth between the different varnish types: glossy, matte and semi-gloss. On the object, the borders between these different shininess zones are made subtler and more natural-looking via a process known as half-toning.

In a nutshell, this involves gradually fading one varnish out by making its spots smaller and more widely spaced apart, while simultaneously bringing in another by making its spots larger and closer together. The human eye doesn't make out the individual spots, but instead just sees a gradual transition from one level of glossiness to another.

The printer has already been successfully used to produce what are being referred to as 2.5-D objects – this means they're somewhat like raised-relief maps, in that they're flat items with contoured surfaces that vary in "elevation" by 5 mm. It is hoped that the technology could ultimately be used to print truly three-dimensional objects such as reproductions of artwork, or lifelike prosthetic devices.

Source: MIT