The 3D printing of certain items could soon get a lot faster, simpler and more eco-friendly. That's because scientists have developed a new 3D printing ink which is easily extruded as a liquid, but then solidifies on contact with a saltwater solution.

When most people think of 3D printing, they picture a commonly used technique known as fused deposition modeling (FDM). This method involves extruding a molten polymer out of a nozzle, building objects up in successively deposited layers as the polymer cools into a solid state.

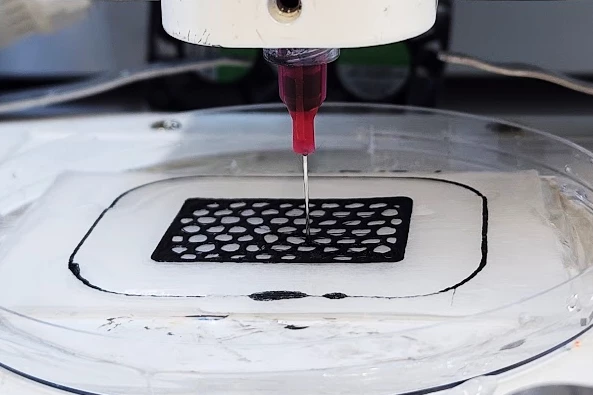

Another technique, called direct ink writing (DIW), also involves extruding stuff out of a nozzle. In this case, however, that stuff is a gelatinous polymer "ink" which chemically transitions into a solid. As compared to FDM, DIW tends to be more cost-effective and energy-efficient, plus it allows for objects to be built out of a wider range of polymers.

One drawback of the technique, however, lies in the fact that toxic chemical catalysts and crosslinkers are often required to initiate and then boost the liquid-to-solid transition. Not only are these chemicals potentially harmful to people and the environment, they're also added in a post-print step that adds to the duration and complexity of the production process.

That's where the new ink comes in.

Developed by Prof. Jinhye Bae and colleagues at the University of California San Diego, it incorporates a liquid polymer solution by the name of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) – or PNIPAM, for short. Functional materials, such as carbon nanotubes or graphene flakes, can be mixed into the liquid.

Because the PNIPAM is initially quite runny, it can be easily extruded out of a needle with very little force. When the ink is extruded into a calcium chloride saltwater solution, the salt ions immediately draw the water molecules out of the ink – it's a phenomenon known as "salting-out." The hydrophobic (water-repelling) polymer chains left in the ink then cluster together, causing the ink to instantly turn solid. Any added functional materials are locked in there, too.

Unlike conventional DIW printing, the PNIPAM method doesn't require the use of any post-print chemicals, and it can be conducted at room temperature. As an added bonus, the printed solid objects can later be converted back into useable liquid PNIPAM if desired.

The technology has already been utilized to print a circuit board that was used to power a light bulb.

A paper on the research – which also involved scientists from Hanyang University in Korea – was recently published in the journal Nature Communications. You can see the ink instantly forming into solid coils, in the video below.

Source: UC San Diego